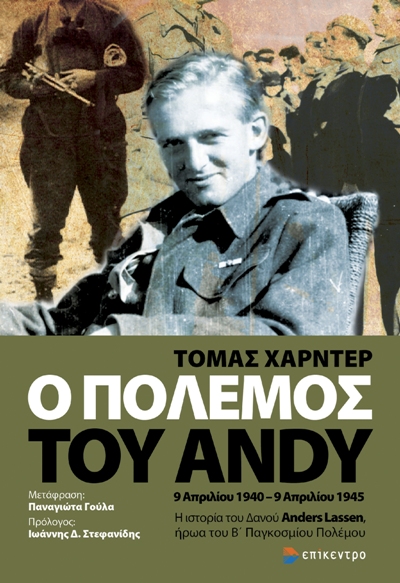

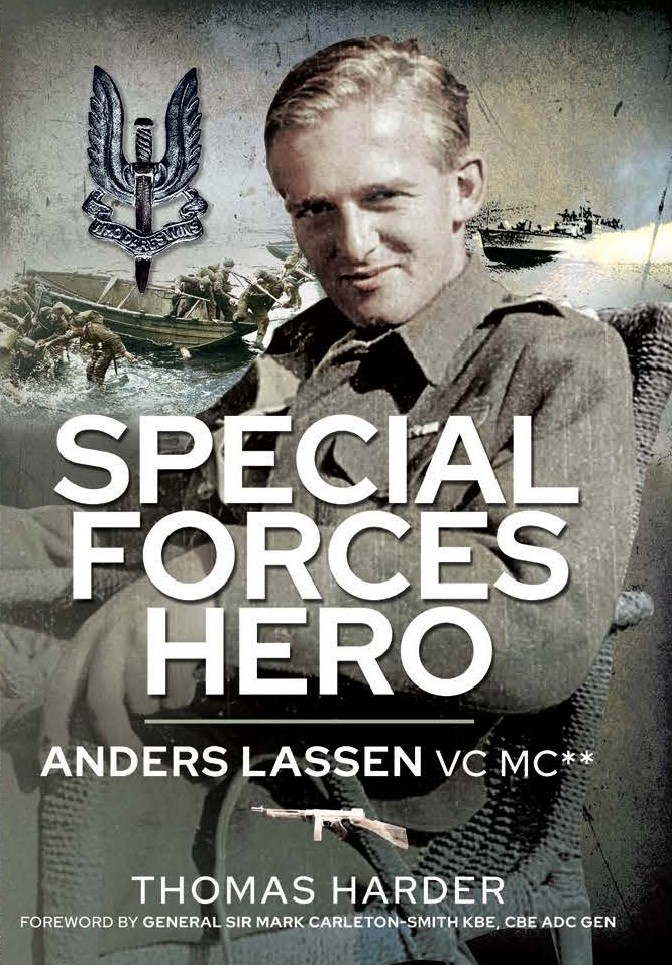

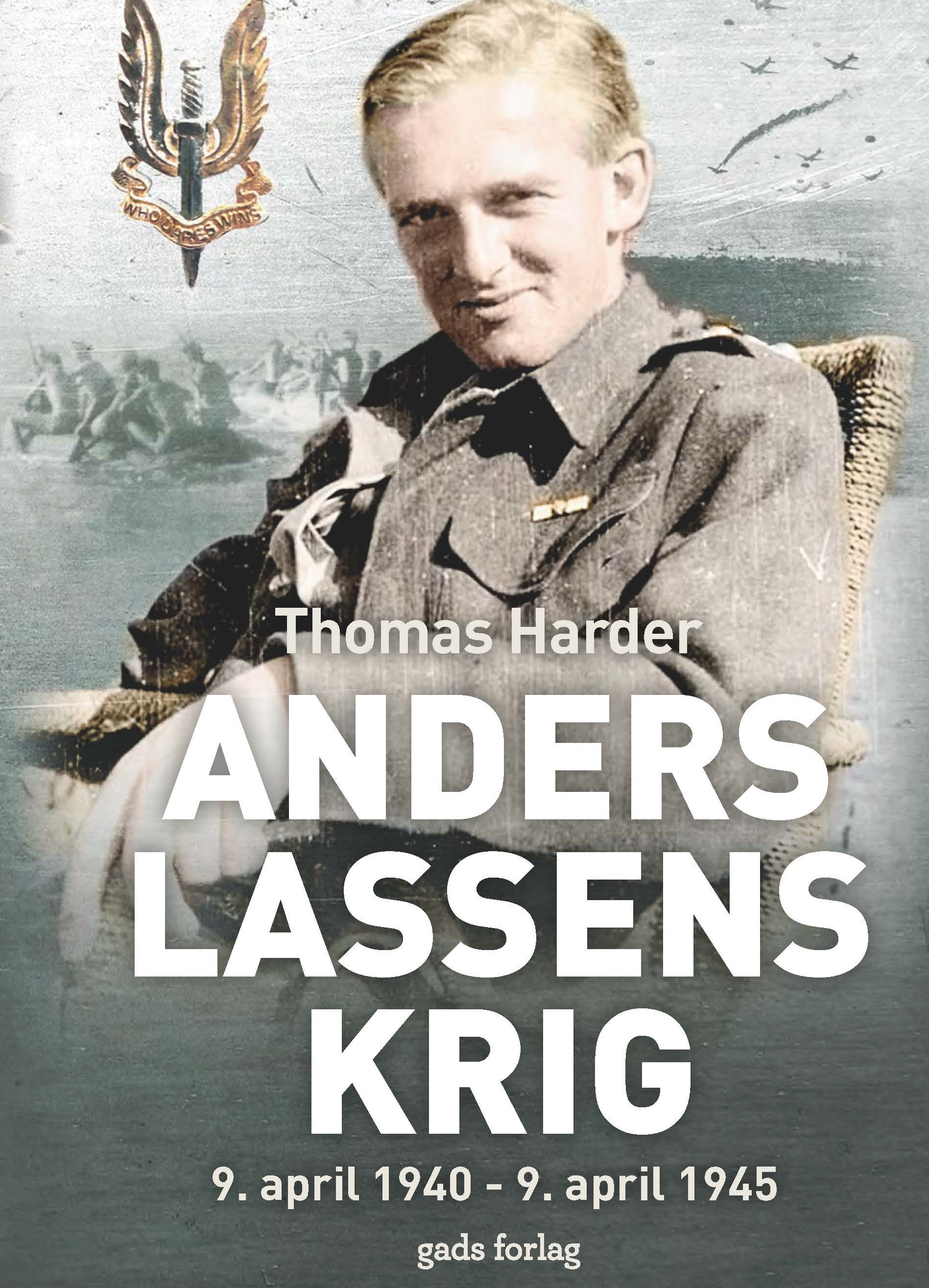

Review of: Thomas Harder: Special Forces Hero. Anders Lassen, VC, MC**. Foreword by General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith. Translated from Danish by Tam McTurk. Yorkshire (Pen & Sword), 2021

Greek version: Athens Review of Books Anters Lassen Iroas Iliadikis Vanafsotitas

Lars Baerentzen[i]

In his magnificent biography of the Danish soldier Anders Lassen, Thomas Harder has ambitious aims: To tell the personal story of the young man who died in 1945, (not yet 25 years of age) and his social background in pre-war Denmark, to tell in often minute detail all that is known of the operations carried out by Lassen and his fellow raiders; to explain the wider background and reasons behind these operations - and on top of that: to give an outline story of how S.O.E. and the ‘special operations’ evolved in British strategy and tactics.

Anders Lassen was a young sailor on a ship outside Denmark on the day when the country was occupied by Germany on April 9, 1940. He was in the British army from 1941 to his death on the Italian front on April 9, 1945. During 1943 and 1944 nearly all Lassen’s activity was in the Aegean and the Italian-occupied Dodecanese, and just after Liberation in October 1944 he was in Thessaloniki and then in Crete, now a Major and in command of Senforce (named from the “Sen” in LasSEN). The book is a biography of Anders Lassen but also a valuable contribution to the history of Greece during World War II.

In copious notes (598 – of which some are small essays) Harder gives the sources for every part of the story, some based on the memories of people who knew him in the war, but lived to tell their story. It seems that Lassen always made a strong impression on people: of admiration - or fear - or often both. Harder uses also official documents, British, German and Italian (for the fighting in the Dodecanese islands in late 1943 – a gamble which turned into a serious British defeat – for which Italian action, or rather inaction, was crucial). Harder typically begins by reconstructing each story in dramatic detail – and then questions whether the story is likely to be true. The notes frequently present various versions of what happened.

The story of Anders Lassen and his heroic exploits has been told many times: The first detailed account of his life was published in 1949 (in Danish) by his mother who was a talented author. She travelled to Greece and to Italy and to England in search of people who had known her son. Others, too, have been eager to describe a Danish war-hero, who had fought “for the right cause” and had done so from early in the war, when official Denmark was collaborating with the occupying Germans. Today, memorials to Anders Lassen are prominent in Denmark, for instance there is a bronze portrait in front of the Museum of National Resistance and at the headquarters of the Danish special forces. <see illustration>.

Thomas Harder’s book on Anders Lassen explains and upholds his fame as a war hero – and also tells of the human cost to Lassen himself and to those around him. Lassen and many other “Special Forces” raiders – Lassen perhaps more than any - were brutal in their dealings with the enemy but often also brutal to each other. Lassen’s own men were physically afraid of him, more afraid of him than of the enemy. But they trusted his instinctive talent for war and felt that his presence added to their own chances of survival.

His fellow raiders were glad when he helped them grab money - from the enemy but also from the golden Sovereigns supplied to them by their own headquarters. Thomas Harder remarks on the raiders’ persistent interest in blowing open every safe they came across. During the brief spell when Lassen had a role of (somewhat undefined) authority in Thessaloniki after the Germans had left, the city was full of people who feared that the Communists would confiscate the money they had gained during the occupation. Some gave the money to Lassen who promised to keep it safe – but then he kept the money for himself, confident (as Harder says) that he would not be around for the owners to reclaim it.

Thomas Harder explains Lassen’s courage largely as an inability to see danger or feel fear. Every time Lassen drove a car on a steep road (whether the enemy was near or not), his passenger was scared. Lassen’s ability to shoot fast to kill, aiming instinctively (as he had learnt when hunting with a bow and arrow in the forest in Denmark)[ii] became legendary. Harder quotes companions who thought, disapprovingly, that he was too fond of killing enemies with his knife. This may surprise when the official S.O.E. training (also quoted) recommended the knife as a quick and silent weapon.

In between battles and during his frequent periods of leave, Anders Lassen – when not in hospital for various illnesses – was to be found in bars (from London to Beirut) drinking heavily and often fighting with other guests. Just after arriving in the Middle East in early 1943, he was offended by something said by his commanding officer, Lord Jellicoe, - and hit him. But Jellicoe “did not want to lose a good man”, and they drove together back to their camp.

However, Lassen’s background among Danish ‘landed gentry’ gave his social life opportunities not open to other rough soldiers. Already during S.O.E. training in England in 1941, he was invited to visit the Danish Ambassador, Count Reventlow, who knew his parents. Lassen wrote a letter in August 1943 to Reventlow and his wife, in a jubilant and respectful tone, to celebrate that the Danish Government in August 1943 abandoned their collaboration with the occupiers and stepped down. Lassen saw this as giving added legitimacy for his ‘patriotic fight’ against the Germans. Thomas Harder also mentions that Lassen allegedly bragged that he had seduced two of the Ambassador’s three female servants.

Lassen’s sexual appetite is often mentioned in the book: In 1941 he had a seemingly stable relation with a woman in Bournemouth who had been widowed twice (thus referred to by Lassen as his “widow with a bar”). An un-named young woman in Piraeus lent Lassen clothes in 1944. While he was serving in Crete in the winter of 1944/45 important meetings seem likely to be held in brothels.

In Helwan, south of Cairo, Lassen was a welcome guest in the house of a Danish couple, Else and Vagn Hoffmann, who ran a cement factory. Perhaps the best photo of Anders Lassen (reproduced on the cover of Harder’s book), was taken in their garden in 1943: a study of a brilliant and complex young man. The photo was taken on August 29, 1943.

By military talent and bravery, Anders Lassen became an officer in the class-conscious British army. Thomas Harder writes (convincingly) that Lassen’s heavy Danish accent made him difficult to ‘pin down’ in the social system. No doubt it also helped that the British army had a lot of room for ‘buccaneers’ who combined a zest for ruthless fighting with a disdain (as Lassen often showed) for normal military discipline. It helped if an unruly warrior (like David Stirling, who formed Special Boat Service) had family connections such as being the neighbour in Scotland of Lord Auchinleck, the C-in-C. Lassen and many others who ignored military regulations and decorum usually got away with it. On a single occasion when Lassen had to show a superior officer that he took his reproach seriously, Lassen did it by kicking out the teeth of one of his own men. No complaint against Lassen was registered.

Thomas Harder’s technique is to use all the precise detail he can possibly extract from the sources to make his story as vivid and realistic as possible. Examples abound and here is one: On their operation in occupied Crete in July 1943 to blow up German aircraft, a helpful local Greek brought some food to the cave where Lassen and his fellows are hiding: “The village policeman Manolis Mourtzakis brought a pitcher of water and fourteen eggs”. 14! No naval boat or other military kit is mentioned without its serial number and other available detail. The method works, undoubtedly, but the reader sometimes wonders if he really needs to know all.

Harder’s addiction to detail is perhaps more fruitful in his persistent efforts to describe the political and the military context of all the diverse raids that Anders Lassen was part of from 1942 to his death in April 1945. The earliest operation was in the Spanish colonial possession off West Africa, the island Fernando Po, in January 1942. Lassen was with a small group who hijacked an Italian passenger ship, the Duchessa d’Aosta, under the eyes of German and Italian officers, who were lured away to a conveniently alcoholic party ashore. The desperate military situation of Britain – and also of S.O.E. as an organization - at this time is well brought out by the fact that the capture of this small liner was seen as an important success (at a time when Rommel was advancing towards Egypt and the battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse had been sunk by the Japanese etc etc).

This success in West Africa led to a short spell when Lassen was tasked with teaching local tribesmen how to fight, but this job was cut short just before Lassen had had time to negotiate the purchase of a wife from a local chieftain. Lassen himself wrote: “The father originally wanted the abominable price of 15 pounds and I would only give 10 pounds.”

Back in England Lassen took part in some raids on the German occupied Channel Islands near the French coast. They were dangerous and costly (also to the raiders), but for the purposes of this review it is best to move on to the chapters on Greece.

Lassen first came to the Middle East because he was chosen by David Stirling to be part of the Special Boat Service (the SBS). On 8 February 1943 he flew from England to Egypt on a B-24 bomber and joined his new unit, SBS, that was part of “1. SAS” (Special Air Service) - a unit that also included some Free French forces and the Greek Hieros Lochos under Colonel Tsigantes. The unit (as Harder remarks) was in a state of chaos because Stirling, its founder and commander, had just vanished during a raid in the Libyan desert. He also mentions that the “Hieros Lochos” was named from a Theban elite corps that defeated the Spartans in 330 B.C. They were sometimes called “The Sacred Greeks” by their British comrades.

Training in their new camp just south of Haifa, Lassen excelled in physical endurance and ruthless resourcefulness: being late on one training trip in French-occupied Syria, he commandeered a French truck, threw its Senegalese driver into a ditch and made it back to the camp on time. But his commander, Jellicoe, had trouble mollifying the French.

On June 23, 1943, Anders Lassen landed in Crete with a team of SBS soldiers to sabotage German aircraft stationed on two German airfields. The attackers themselves were not told, but this operation was part of the huge deception plan aimed at making the Germans believe that Greece and not Sicily was the target for an Allied invasion. The same plan was also behind Operation “Mincemeat” (“The man who never was”) and it was also the reason why the Allied Military Mission in Greece, under Myers and Woodhouse, were ordered to step up sabotage all over Greece at the same time.

In terms of German aircraft destroyed, the raid in Crete was not very successful, but it did cause upheaval in the island and very many Cretans were killed by the German army in reprisals. Lassen and his fellow raiders escaped from their hiding-place on the south coast with two German prisoners (whom they would otherwise have killed) when a motorboat arrived at the last moment and took them to Egypt where they soon enjoyed a large breakfast which included their German prisoners as guests.

The autumn of 1943 was dominated by the confused fighting on the Dodecanese islands, and Anders Lassen and the Special Boat Service took part in many of these operations which ended with a costly British defeat. These battles are described in detail by Smith and Walker in their 1974-book “War in the Aegean” (a book missing in Harder’s extensive bibliography though Lassen’s fighting on Simi is featured quite prominently on p.151.)

The operation started in September – though the Americans opposed it as an unwanted distraction from the main front in Italy. But the temptation was too great (as Harder well explains). For if the British had succeeded in gaining support from the bulk of the Italian forces and had taken control of the islands and put RAF bases on them, the prize would have been very great: Perhaps it had brought the elusive Turks into the war on the Allied side – and the liberation of Greece and the end of the war in the Balkans would probably have been better in accord with British aims. But the British gamble failed for two main reasons: The Germans acted quicker and had more luck than expected - and the Italian Admiral on Rhodes hesitated and had neither courage nor luck.

Harder describes the fighting on Leros and Kos and other islands - not just Lassen’s part - in riveting detail. During the German parachute attack on Leros the British defenders shot and killed many Germans as they were still suspended under their chutes. Harder is typically precise: 280 of the Germans were killed or wounded before they landed. The Germans won that battle anyway. Morale among the British (as Harder discreetly says) was not helped when the British commander moved his HQ from Leros to Samos as soon as SIGINT-intelligence had foretold the German attack. But fighting was fierce in Leros, Kos and elsewhere. In the fighting in Simi, “Lassen’s actions earned him his third Military Cross”. In the end, German seaborne attacks and virtually unopposed action by the Luftwaffe expelled all British forces and confirmed the Turks in their neutrality. Serious British losses had been of no avail.

Perhaps (one may ask) another deception scheme was the real reason behind the British attempt to occupy the Dodecanese? Surprisingly, it seems the opposite is true: The “battle for the Aegean Sea” (to which Harder devotes two full chapters) in fact destroyed some carefully laid deception plans by making it obvious that the British strength in the Middle East was far weaker than deception had made it seem to be.

In the Spring of 1944, Lassen and the SBS and other Special Forces went back to carrying out random attacks all over the Aegean. Harder writes: “Raid in the Eastern Mediterranean were designed to divert German attention away from Operation Overlord, the D-Day landing in Normandy. . . .Once again, those doing the work were unaware of the bigger picture”. Today we know that all this was part of operation Zeppelin, the codename for the Mediterranean part of operation Bodyguard, the overall deception plan to protect the invasion plan.

The raid on Santorini began on 19 April 1944. “Lassen’s mission was to destroy … ships that sailed for the Germans, destroy enemy communications equipment, neutralise soldiers on Santorini, and to attack any other targets that he identified” according to the SBS “Instruction no. 13 – Thira”, which Harder quotes in note 429. As told in painstaking detail over many pages, the raid was bloody for both sides. Lassen wrote in his report: “There is no doubt that shooting up barracks at night requires a great deal of skill and experience, such as only the older men in the S.B.S. have.” On Santorini Lassen met an American officer, Geoffrey Kirk, who wrote in his much later (1997) memoir that Lassen was “one of those people who are quite fearless and also, at times, quite ruthless, a potential berserker. A truly heroic figure in the Iliadic sense.” (Kirk was a classicist) Harder takes issue with some of Kirk’s account in one of his ‘note-essays’ (437).

By the summer of 1944, the end of the German occupation was in sight. After brief service in the Adriatic, Lassen was back in the Aegean from mid-September and he took part in the British return to Athens, staying for some days in the Grande Bretagne. But then Lassen and his force (M Squadron) which was the core of “Scrumforce”, a reconnaissance outfit under Lassen’s command, was sent north towards Thessaloniki.

Early on Monday, 30 October, Lassen led Scrumforce into Thessaloniki. Harder here quotes an eye-witness, professor John O. Iatrides, who lived with his parents in a side street off Queen Olga Avenue: “For a few moments we watched a single jeep go by, carrying four or five <?> men in khaki British field uniforms …Could that have been Lassen’s jeep? Impossible to say!”

Harder is right to say only that the young Iatrides “perhaps” saw Lassen and his jeep, but as it may well have been the only jeep in northern Greece, I believe the probability is high.

As said at the beginning of this review, Thomas Harder’s story of Anders Lassen is also a contribution to the history of the British involvement in Greece during World War II. This is especially true of the chapters at the end of the book, about the Greek Liberation, Lassen’s time in Thessaloniki and in Athens and finally in Crete as commander Sen-Force. Here Lassen was directly involved in the confrontation between the Communists and their opponents, both before and after the Dekemvriana. But he left Athens just before the fighting broke out and his role both in Thessaloniki and in Crete was to help avoid open conflict. Harder does not suggest that Lassen’s role or views differed from those of other British officers.

The battle in northern Italy at Lake Comacchio, when Lassen was killed on April 9, 1945, in a minor skirmish at a time when the German defeat was a certainty, took place five years to the day after the occupation of Denmark. Anders Lassen behaved with reckless bravery, but no different from in so many other battles. Thomas Harder explains in detail why and how Lassen was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously. It was surely well deserved – but would not have happened without influential friends who made it happen.

Anders Lassen had a younger brother, Frants Lassen, who also joined the S.O.E. and was parachuted into Denmark where he worked with the Danish underground until he was arrested by the Gestapo and tortured. He lived until 1997, and his story is told in one of Harder’s “note-essays” no 236

The book is well illustrated with many good photographs.

One should be wary of calling any book a ‘definitive’ study of any person or subject. However, unless new evidence appears, it is hard to see that a more comprehensive, fair and convincing study of Anders Lassen could be written.

[i] An interest must be declared: The writer was asked in 2017 by Thomas Harder to help him revise Greek aspects of the first Danish version of his book on Anders Lassen.

[ii] In the Summer 1941 Anders Lassen sent a letter to the British War Office, suggesting the use of the bow and arrow as a useful weapon in the war. The text is reproduced in his efficient if not quite correct English. The War Office replied (strangely) that the use of this weapon would be “inhumane”.