Special Forces Hero is based on the 4th revised and enlarged edition of Anders Lassens krig, Anders Lassens krig which was originally published in Danish in 2010 and has since appeared in several new editions and reprints. For every new reprint or edition the book has been slightly – in some cases, more than just slightly – improved thanks to corrections and new information offered by the various researchers and experts who have been helping me throughout this decade long work-in-progress, by kind readers or, in many cases, by people who had particular knowledge of the events described, often because their fathers or grandfathers had participated in them. I am very grateful for all these contributions. Keep them coming!

After the publication Special Forces Hero and Ο Πόλεμος του Andy in early 2021, the Dutch researcher Niels Henkemans (twitter.com/niels_1944) made me aware of certain German documents regarding Operation Basalt (Sark, 3-4 October 1942) which I had missed when I wrote the chapters on Operation BASALT a dozen years earlier, notably the death certificates of the German soldiers who died on Sark on 3-4 October 1942 and certain reports from local German army units to higher commands. This material allowed me to clear up some of the loose ends of the story. The following is a revised version of the relevant chapters of Special Forces Hero. So far, it has been included in the Danish audio book version of Anders Lassens krig audio book verson of Anders Lassens krig (January 2022) and in the 5th revised and expanded edition of the printed book (April 2024).

Articles, reviews, video talks etc. on Lassen

Operation BASALT, Sark, 3–4 October 1942

An initial attempt to raid Sark, on the night of 19–20 September, had to be abandoned due to an unfortunate combination of wind and currents. Appleyard and his men tried again on the night of 3–4 October. The mission was preceded by the usual study of aerial photographs, guidebooks and multiple other sources, including the Appleyard family’s own cine films from a holiday on the island.

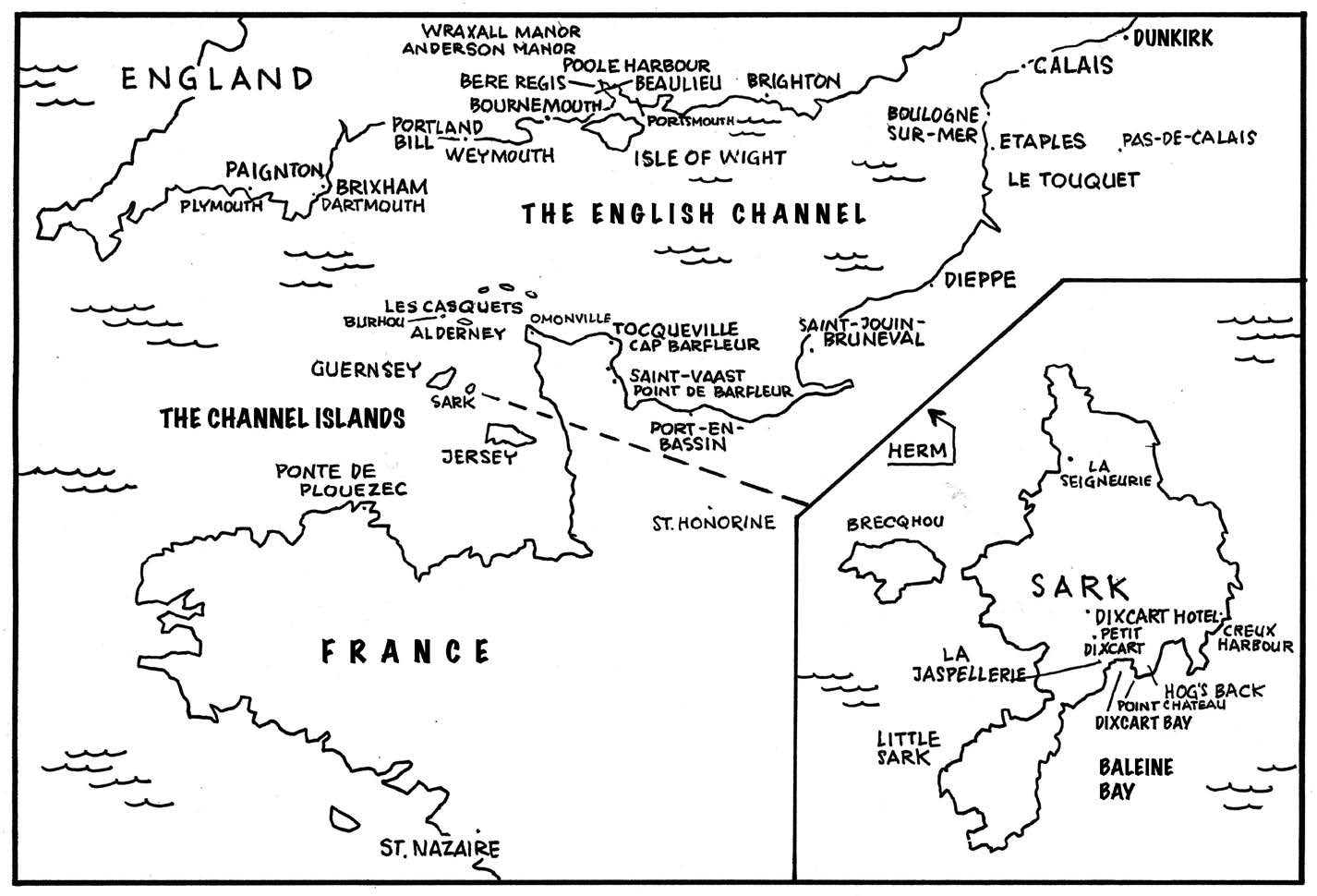

MTB344 sailed from Portland Bill at 19:03. The wind was light and variable, but mainly south-easterly, and the sea was calm, with a light swell. Visibility was four nautical miles – but due to mist, only one along the coast. The force under Appleyard’s command consisted of seven men from the SSRF, including Anders Lassen and his companion Denis Tottenham from Maid Honor, Captain Colin Ogden-Smith, Captain Patrick Laurence Dudgeon, who had also been involved in Operation Dryad, Ogden-Smith’s brother Bruce (a sergeant) and Captain Philip Pinckney from 12 Commando, along with four of his men, lance sergeant (a corporal acting in the rank of sergeant) Joseph Henry “Tim” Robinson, lance corporals Jimmy Flint and Horace Stokes and gunner Eric Forster, making a total of 12 raiders. Captain Warre from “M.E. raiding group” went along as an observer. The purpose of the expedition was to take prisoners and gather intelligence about German defences.

Pinckney was a talented and brave officer. He was also an avid ornithologist, botanist and hunter, passionately preoccupied with finding new ways for soldiers to “live off the land”. He had taught at the commando schools in Scotland, where his penchant for grasses, beetles, raw snails and other unorthodox foodstuffs had made the otherwise very well-liked officer widely feared.

MTB344 dropped anchor near Point Château, where the steep Hog’s Back promontory juts out into Baleine Bay. Moments before this, a German observation post on the southern peninsula Little Sark had asked MTB344 to identify itself using a Morse lamp. Appleyard had replied that they were Germans seeking shelter for the night in the bay. The Germans took no further action.

The raiders rowed ashore, and Lassen, acting as lookout on the bow, guided the boat right up onto the beach. For once, his comrades landed with dry feet. Less fortunately, they had landed in the wrong place – not on Sark, but on a small rocky island off the tip of Hog’s Back. A second, successful attempt was made, and by 23:30 everybody was on dry land and in the right place. Second Lieutenant Young and Tottenham were to guard the boat – which lay in deep water, a safe distance from the rocks, secured by a kedge anchor and a rope fastened to the shore.

Lassen was sent to scout ahead, climbing the steep 160-foot crag to the top of Hog’s Back to look for a rumoured machine-gun position. The rest of the men followed slowly in his wake. The darkness and loose rocks hindered this dangerous progress, but by midnight the whole force had reassembled at the top. Lassen told them that he had found no German positions anywhere on Hog’s Back.

The landing site was neither mined nor guarded as the Germans thought that the steep cliffside and the difficult approach from the sea – not least the strong currents – made any attempt at landing highly unlikely. According to a report from the German LXXXIV Army Corps, responsible for Sark, to the German 7th Army, covering the coast of Brittany and Normandy, conditions around Point Chateau were so difficult that the raiders must necessarily have been aided by a former resident of Sark with local knowledge or by agents on the island with whom they communicated by means of carrier pigeons. The British files on the operation mention neither local helpers nor agents but contain an extract of a guidebook describing the difficult ascent undertaken by Lassen and his comrades.[1]

The raiders now moved north, along the top of the promontory, until they saw something that reminded them of British Army prefabricated Nissen huts and an aerial mast. They immediately stormed the site, but the antenna turned out to be just a flagpole and the Nissen hut was part of a shooting range. The advance continued through dense thickets of bracken and gorse. The raiders proceeded in single file with Appleyard taking point, Lassen in the middle of the column, along with Corporal Flint and another raider, and with Captain Pinckney at the rear. After some time, they heard a German patrol approaching. They scurried off the path and hid in the bushes until the Germans passed by and disappeared into the darkness. No more patrols were encountered, but there were several false alarms whenever one of the men stepped on a dry twig or something moved in a thicket.

At 01:15, they reached the group of small buildings known as Petit Dixcart, the main target of the raid. Two men were sent in to reconnoitre. All of the buildings turned out to be empty and abandoned. Appleyard led the men through the dark toward the secondary target, La Jaspellerie – a larger, detached building atop a small hill, approx. one mile inland, on the other side of a small gorge. The main force remained hidden while three men searched the outhouses and the exterior of the main building. They found a French door to the south-east. The raiders stormed it at 01:50. The ground floor was empty, but Appleyard and Corporal Flint found the owner on the first floor. Forty-one-year-old Frances Pittard seemed unperturbed by being awoken by two armed men with blackened faces. She was the widow of an army doctor and the daughter of a naval officer who lived in England, as did her daughter. She may have had family connections to military intelligence, and it is possible that Appleyard knew her from his holiday on the island. At any rate, he and another member of the force spent about an hour talking to her while the rest of the men secured the building. Mrs Pittard brought out a map and told them in detail about the German fortifications and minefields, the number of soldiers, where they were billeted, their morale, etc. She gave Appleyard the latest edition of the local newspaper, Guernsey Evening Star, which reported that the Germans intended to deport 2,000 able-bodied men from the islands, as well as other pamphlets and interesting papers.

Mrs Pittard told that the German soldiers on the island were below average height and behaved kindly and respectfully to the islanders. The officer in command was a first lieutenant Herdt, a quiet, small, bespectacled man who had been a schoolmaster before the war. No German soldiers were billeted at the nearby Dixcart Hotel, but five sappers who had been working on the harbour facilities at Creux since 23 September were staying at the annexe of the hotel, 5-600 meters southwest of the German quarters containing the garrison’s reserve.[2]*

The German garrison, the size and organisation of which Mrs Pittard obviously cannot have known in any detail consisted of approximately 300 soldiers from the 6th and 14th Companies, Infantry Regiment 538 of the 319th Infantry Division supplemented by a heavy machinegun platoon, a heavy mortar group with four heavy machineguns and two heavy mortars, three antitank guns, three flamethrowers in fixed positions and a group of border guards with a light machinegun, as well as 939 S-mines (anti-personnel landmines that, when triggered, launched into the air and exploded at waist height in a hail of steel fragments), spread over 22 different minefields.[3]

The raiders set off again, heading toward the hotel. They had already been on the island for an hour longer than planned, so a corporal was sent back to the Goatley boat to signal to Bourne on MTB344 that everything was in order and that he should keep waiting for them.

Appleyard sent his men towards the annexe. They advanced in formation, but there were no Germans to be seen. Breaking the door down made a noise, but not enough to alert the occupants. They forced their way into a room with a door at the far end. Lassen opened it. It led into a corridor with half a dozen doors along the two sides. Appleyard ordered his men to take one each and enter at his signal. The five Germans in the building were sleeping in separate rooms and the raiders overpowered them with little difficulty. The prisoners were brought into the hall. A raider kept them covered while their hands were tied behind their backs with rope, which the raiders had brought along for that purpose, and their uniforms and rooms were searched. They were then led outside under a group of trees.

However, in violation of SOE procedures, the prisoners had not been gagged. Once they emerged into the moonlight and saw how few attackers there were, they began to shout. Appleyard yelled “Get the prisoners to shut up!” In the ensuing melee, a prisoner, corporal Klotz, managed to free his hands, knock down his guard and disappear into the darkness. The other prisoners tried to free themselves as well. Captain Dudgeon hit one of them, corporal Just, on the head with a pistol. The weapon was not secured and a shot went off. Dudgeon thought that the shot had hit Just in the head, however the corporal was only bruised by the blow and managed to get away in the confusion. Two other Germans, the 28 years old sergeant August Bleyer and the 30 years old corporal Heinrich Esslinger, were less fortunate: Their attempt at escaping ended with them both being killed by knife wounds and shots to the stomach; at least one of them was stabbed, and possibly shot, by Lassen. The raiders probably tried to kill the obstreperous prisoners silently with their knives, as they had been taught to do at Arisaig, shooting them only as this did not work out. Beyer appears to have died immediately, Esslinger a few hours later.[4]

Irrespective of whether Lassen used his knife on both August Bleyer and Heinrich Esslinger or on only of them, there was a world of difference between this and the two killings he thought he had perpetrated during Operation Barricade. During the fighting in front of Post 4, Lassen fired his machine gun into the darkness, in the direction of voices or shadows. On Sark he was in close physical contact with his victim.

Lassen’s last note in his hunting journal reads: “Was on again the other day trickiest and hardest work I’ve ever done used my knife for the first time.”

The fifth German, senior corporal Weinreich, kept quiet and put up no resistance.

As shouts were heard in the darkness in the direction where Klotz and Just had disappeared Appleyard ordered an immediate retreat.

The fighting outside the hotel annexe lasted from 02:30 until 02:50. The raiders made it back to the beach after a frantic dash over difficult terrain. The exhausted, pyjama-clad Weinreich had to be dragged along for the final stretch. At the boat, they met the corporal who had been sent to report the delay. The terrain’s dense vegetation had delayed him, too. Had Lieutenant Bourne not decided to wait beyond the scheduled time – he opted for 03:50 but not a minute longer – MTB344 would have been on her way back to England.

The raiders left Sark with their German prisoner at 03:35, and were back on board MTB344 at 03:45. Bourne set sail for England immediately, and they docked in Portland at 06:33.[5]

Operation BASALT - Loose Ends: Redborn, Foot, Kemp

In his report on Operation Basalt Appleyard wrote that his men had shot and probably killed four Germans, whereas the correct figure, based on German reports and death certificates, was two dead and one wounded by a blow to the head. Appleyard did not mention that two of the Germans had not only been shot, but also stabbed. (He may have found the use of knives insignificant compared to the shooting, or he may have had other reasons for preferring not to mention the knifings). It’s important to bear in mind that Appleyard had to rely on his own and his comrades’ recollections of the dramatic and confused events in the nightly darkness, whereas the German reports were based on records from the various local units and, not least, on physical evidence found in the days after the raid and on the forensic examinations of the dead soldiers.

Although it is fairly clear what happened on Sark during the night between 3 and 4 October 1942, two alternative, and in all likelihood erroneous, accounts, both involving Lassen, keep appearing. The source of the first one is a Bombardier Redborn who supposedly took part in the raid and later told Lassen’s mother[6] that after the visit to Mrs Pittard he and Lassen were sent ahead to reconnoitre the hotel’s surroundings. They spotted a German guard which they reported to Appleyard, who sent them back to take care of him. Lassen remarked, jokingly, that it would have been helpful to have a bow and arrow with him.

At Arisaig, Lassen had learned that, ideally, two men were required to kill a sentry – one to hold him while the other stuck a knife into his kidneys (or stomach if his equipment got in the way). The helper could also seize the victim’s rifle to stop it making a noise as it hit the ground. It was also easier for two people to hide a corpse. Lassen, however, insisted on dealing with the German on his own. He and his comrade hid for a while, watching the sentry The other raiders arrived just in time to catch a glimpse of the German before Lassen crept up on him. There was a stifled scream, and then Lassen returned.

The story of Lassen stalking the German sentry is undermined by two important facts: According to German records only two German soldiers were killed in combat on Sark that night, and it has not been possible to confirm that a soldier called Redborn took part in the raid – or that he ever existed. Redborn seems to have made his first appearance in Suzanne Lassen’s book on her son which appeared in Danish in 1949 and in English in 1962. Suzanne Lassen described Redborn as a modest little man with a large black moustache, who was a ladies’ milliner in civilian life. Redborn’s account is quite expansive and contains a number of details which may be true and others which fit neither with Appleyard’s report nor with the German files – the most conspicuous one being the dramatic story of the killing of the sentry. Redborn was probably invented by Suzanne Lassen, and his account was then repeated by Langley, Ramsey, et al. She may have wanted to combine information from several sources in a single narrator’s voice, or perhaps for reasons of discretion or confidentiality she felt compelled to conceal the identity of her source. Whether the fictitious additions were made by her or by her source (or sources) remains unknown.[7]

Another, apparently equally fictitious, story of a knifing was told by the official SOE historian M.R.D. Foot who in SOE in France theorised that a German prisoner was stabbed to death while resisting being dragged off to the boat. Lassen’s comrade Peter Kemp tells the same story in his own war memoirs.[8] This story presumes that the raiders took not one, but two prisoners from Dixcart Hotel, only one of whom made it to the boat alive, while the other was stabbed to death when he refused to obey. This version probably derived from the use of knives in front of the Dixcart Hotel annexe, which Appleyard didn’t document in his report, but which Kemp, who did not participate in Operation Basalt, will probably have heard of from his comrades. In his wartime memoirs, published more than a decade after the events, Kemp may have deliberately distorted the facts or may simply have remembered the story incorrectly. Foot undoubtedly knew Kemp’s memoirs.[9]

Operation Basalt – Aftermath

The confusion about what actually happened on Sark on 4 October 1942 stems in part from the propaganda war waged in the weeks that followed Operation Basalt.

Hitler was already furious about secret instructions the Germans had found on Canadian troops involved in the attack on Dieppe on 19 August 1942 that any prisoners were to have their hands bound so that they could not destroy secret papers. This was interpreted as a violation of the Geneva Convention on the protection of prisoners of war (which the German Wehrmacht itself had violated on countless occasions). Nor did it help that it turned out that some German prisoners actually did have their hands tied behind their backs – and some were even shot by British or Canadian troops who had taken more prisoners than they could cope with.[10] There were also rumours that the Commandos who took part in the raid on the Lofoten on 3 March 1941 had been encouraged to shoot German soldiers before they could surrender. (The British took 216 prisoners at Lofoten, many of whom had their hands tied.) In addition, much of the rhetoric that surrounded the Commandos contributed to the impression that they were criminals – an image Hitler probably believed in, and which his propaganda machine certainly found easy to exploit. Now, there was the treatment of the prisoners on Sark.

On 7 October, the Führer’s HQ proclaimed that all of the British soldiers the Germans had captured at Dieppe would be “shackled” or “bound” (“Fesselung”) until the British War Office confirmed that in future it would ensure that the British forces complied with the ban on tying up prisoners of war.[11]

The British government threatened to retaliate. On 9 October, the Germans announced that 1,376 British soldiers had been shackled. The next day, the British shackled a similar number of German POWs in Canadian camps. The Swiss government offered to mediate and suggested that both parties remove the shackles at the same time. The British did so on 12 October, and the Germans followed suit once they had received an assurance that the British would ban the practice completely.

“The shackling crisis” was over, but Hitler was not finished with the Commandos. On 18 October 1942, he issued the “Commando Order”, which instructed the Wehrmacht to kill every last man involved in “so-called commando operations”, whether they wore uniforms and were armed or not, whether they were engaged in combat or on the run, and even if they “appeared to make moves to surrender, in principle no mercy is to be shown to any of them”.[12]*

The German military authorities carried out an in-depth investigation of the events on Sark of 3–4 October 1942. They believed that the islanders had helped the raiders. When they interrogated Frances Pittard, she confessed that she had given them detailed information on the garrison and defence installations.[13]

Mrs Pittard, Miss Duckett and Miss Page (who owned the Dixcart Hotel) and other specially selected Sark residents were deported to France. To prevent further attacks, the Germans sent reinforcements to Sark and extended the minefields, further restricting the residents’ already limited freedom of movement. As elsewhere in occupied Europe, there was widespread reluctance among civilians to help saboteurs, partisans or, in this case, raiders whose actions triggered German reprisals and counter-measures.[14]

Books etc. mentioned in the text and/or notes

Foot, M.R.D. (1966): SOE in France, An Account of the Work of the British Special Operations Executive in France 1940–1944, HMSO, London.

Fournier, Gérard & Heintz, André (2006): “If I Must Die …”. From “Postmaster” to “Aquatint”, The Audacious Raids of a British Commando 1941–1943, Orep Editions, Cully.

Kemp, Peter (1958/1960): No Colours or Crest, Cassell, London.

Langley, Mike (1988/2016): Anders Lassen VC, MC of the SBS. Pen and Sword

Lassen, Suzanne, Anders Lassen VC, Frederick Muller, 1962

Lee, Eric (2016): Operation Basalt, The History Press, Brimscombe Port

Lett, Brian (2013): The Small Scale Raiding Force, Pen and Sword.

Messenger, Charles (1985): The Commandos 1940–1946, foreword by Brigadier Peter Young,

DSO MC MA FSA, William Kimber, London

Parker, John (2000/2005): Commandos, The Inside Story of Britain’s Most Elite Fighting Force,

Bounty Books, London.

Ramsey, Winston G. (1981): The War in the Channel Islands Then and Now, After the Battle.

Robinson, Graham (2015): ‘Sergeant Joseph Henry ‘Tim’ Robinson and the men from E Troop 12 Commando’, https://operationbasalt.apps-1and1.net/page/4/

Robinson, Graham (2016): ‘Remarks by Graham Robinson on Sark, 21 May 2016’, https://operationbasalt.apps-1and1.net/remarks-by-graham-robinson-on-sark-21-may-2016/

(The bulk of this text was translated from Danish by Tam McTurk. Provisional translation of additions and revisions by Thomas Harder).

© Thomas Harder 2022

[2]”Force Commander’s Report” and ”Intelligence Report” (DEFE 2/109). »The investigations have shown that the successful British attack on the Channel Island of Sark was made possible by a British citizen who provided the detailed information on the island’s garrison and defences.« (Report from Abwehrleitstelle Frankreich to OKW, 22 December 1942, RW 49/97). On the German sappers and main garrison: ID 319 to LXXXIV AK, 6.10.41,”Bericht über den Überfall an Sark”, RH 24-84/6.

[3] Generalkommando LXXXIV AK to AOK 7, 4.10.42; Generalkommando LXXXIV AK to AOK 7, 6.10. 42, RH 24-84/6; AOK 7, Ia to Ob West, 23.10.42, RH 20-7/69.

[4]”Force Commander’s Report” (DEFE 2/109). On the discovery of rope and various pieces of equipment left behind by the raiders: Generalkommando LXXXIV AK to AOK 7, 6.10.42, RH 24-84/6. Death certificates: Kartei der Verlust- und Grabmeldungen gefallener deutscher Soldaten 1939-1945 (-1948), Bundesarchiv B 563-2 Kartei. Berlin, Deutschland: Deutsches Bundesarchiv. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61641/

[5] Ramsey 1981/2005, pp. 148–157; Langley 1988/2016, pp. 108-112; SOE Channel Islands No. 1, Report on Operation “BASALT”, signed Appleyard, 6 October 1942, HS 6/304; DEFE 2 109. On Redborn: Lassen 1949/1965, p.51-54. Doubts about the existence of Redborn and a meticulous study of the available sources referring to the participants in Operation Basalt: Robinson 2015 and 2016. See also Lee 2016.

[6] Lassen 1962, pp. 51-54.

[7] Redborn’s account appears in i.a. Winston G. Ramsey, The War in the Channel Islands Then and Now (1981); Mike Langley, Anders Lassen (1985); Sir Peter de la Billière, Supreme Courage, Heroic Stories from 150 Years of the Victoria Cros (2004); and Brian Lett, The Small Scale Raiding Force (2013).

[8] Foot 1966, p.187; Kemp 1958/60, p.63.

[9] A third German soldier died on Guernsey on 4 October 1942, the 35 years old senior corporal of Flak-Regiment 39 Peter Oswald. His gravestone stands in the cemetery of Creux on Guernsey, next to Bleyer’s and Esslinger’s. According to his death certificate Oswald was neither stabbed nor shot but was killed in an accident causing a compression of the fifth vertebra leading to paralysis and death.

According to some versions of the story of Operation Basalt, the purpose was to bring back a Polish SOE agent who was hiding on the island. (Fournier & Heintz 2006, pp. 234–235 and Messenger 1985, p. 158.) This version is based on an eyewitness account from a certain Leslie “Red” Wright, who served in the Royal Marines from 17 June 1942 to 16 January 1946, but neither in the Commandos nor the SSRF. At no time did Wright leave Britain during his military service, but he managed nonetheless to fool journalists, writers and many others with his carefully prepared tall tales. Excerpts of his service records, etc. are in the SAS Regimental Archive.

[10] Parker 2000, p.111.

[11] RW 49/662; Ramsey 1981/2005, p. 156; Langley 1988/2016, pp.109-112.

[12] The full text is available at: http://www.documentarchiv.de/ns.html. Retrieved 6 December 2017. There was apparently a certain degree of uncertainty about how the order should be executed – but perhaps some officers just did not like the order to shoot enemy prisoners. In June and November 1944, the head of Sipo SD/IV A2a Amt M, Colonel Hansen, impressed upon OKW several times that when the Wehrmacht took enemy commandos prisoner, the unit concerned was responsible for carrying out the order. The prisoners were not, as was the standard practice for other enemy combatants, to be handed over to Sipo, but immediately “killed in combat” or “while escaping”. If it was considered appropriate to interrogate the prisoners, the Sipo should be brought in, but afterwards the unit was still responsible for shooting the commando. (RH 49/662; RW 5/244; RW 5/502).

[13] Letter from Abwehrleitstelle Frankreich to OKW, 22 December 1942, RW 49/97.

[14] Ramsey 1981/2005, p.150; Messenger 1985, p.160.