Dearest Kek

By Thomas Harder & Lene Ewald Hesel

Samples translated by Tam McTurk

Preface

It all began with a phone call out of the blue in May 2011. A friendly voice introduced herself to Lene as “a voice from the past: I am the 17-year-old girl who had lunch with Anders in London in 1942.” She was referring to Anders Lassen, a highly decorated Danish hero who served in the British Army in World War II, about whom Thomas had published a biography six months previously. Unfortunately, the girl’s surname had been misspelt in the book (it was in fact her later, married surname). Eighty-six-year-old Ellen Branth, née Karsten, just wanted to politely set the record straight

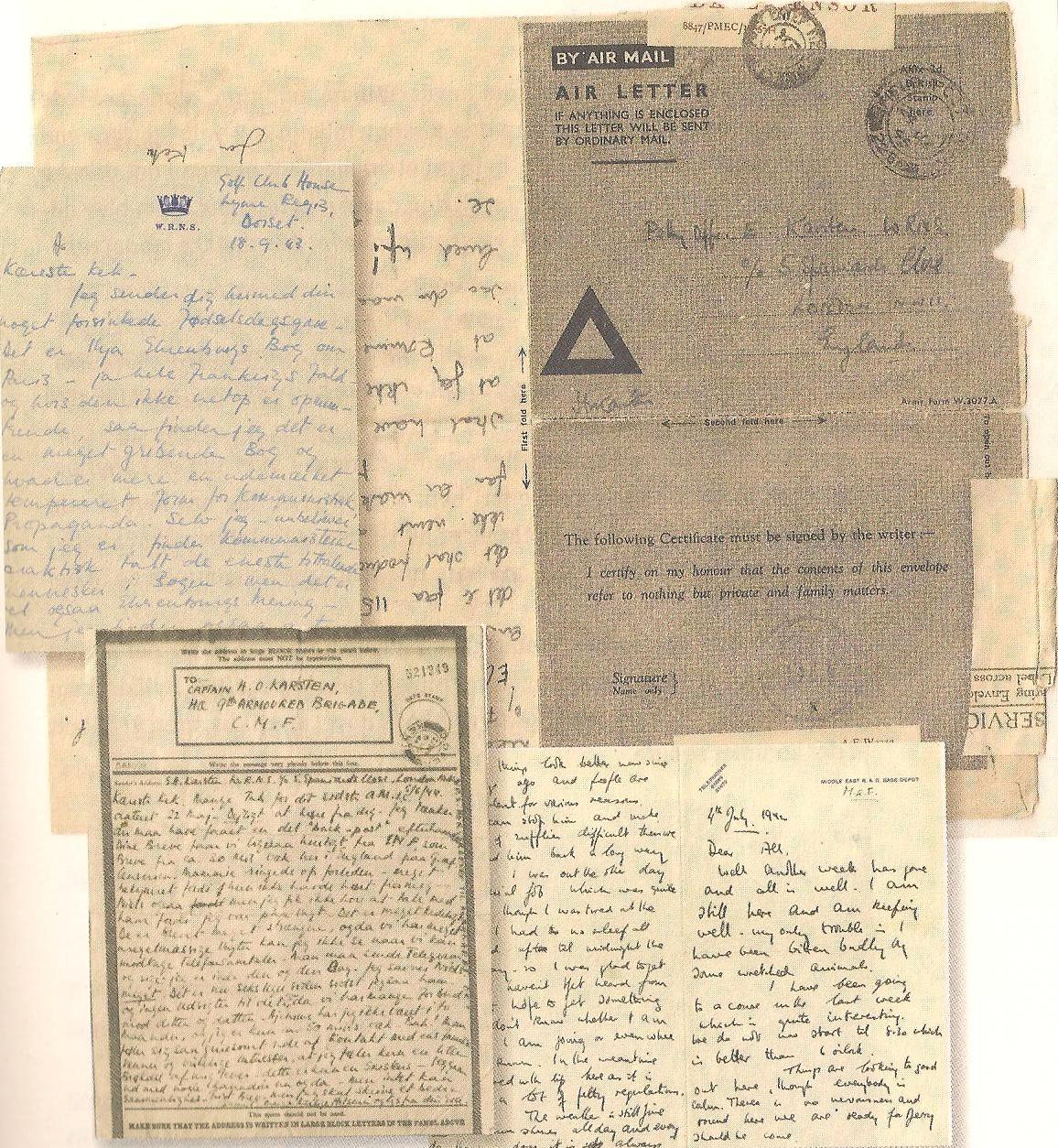

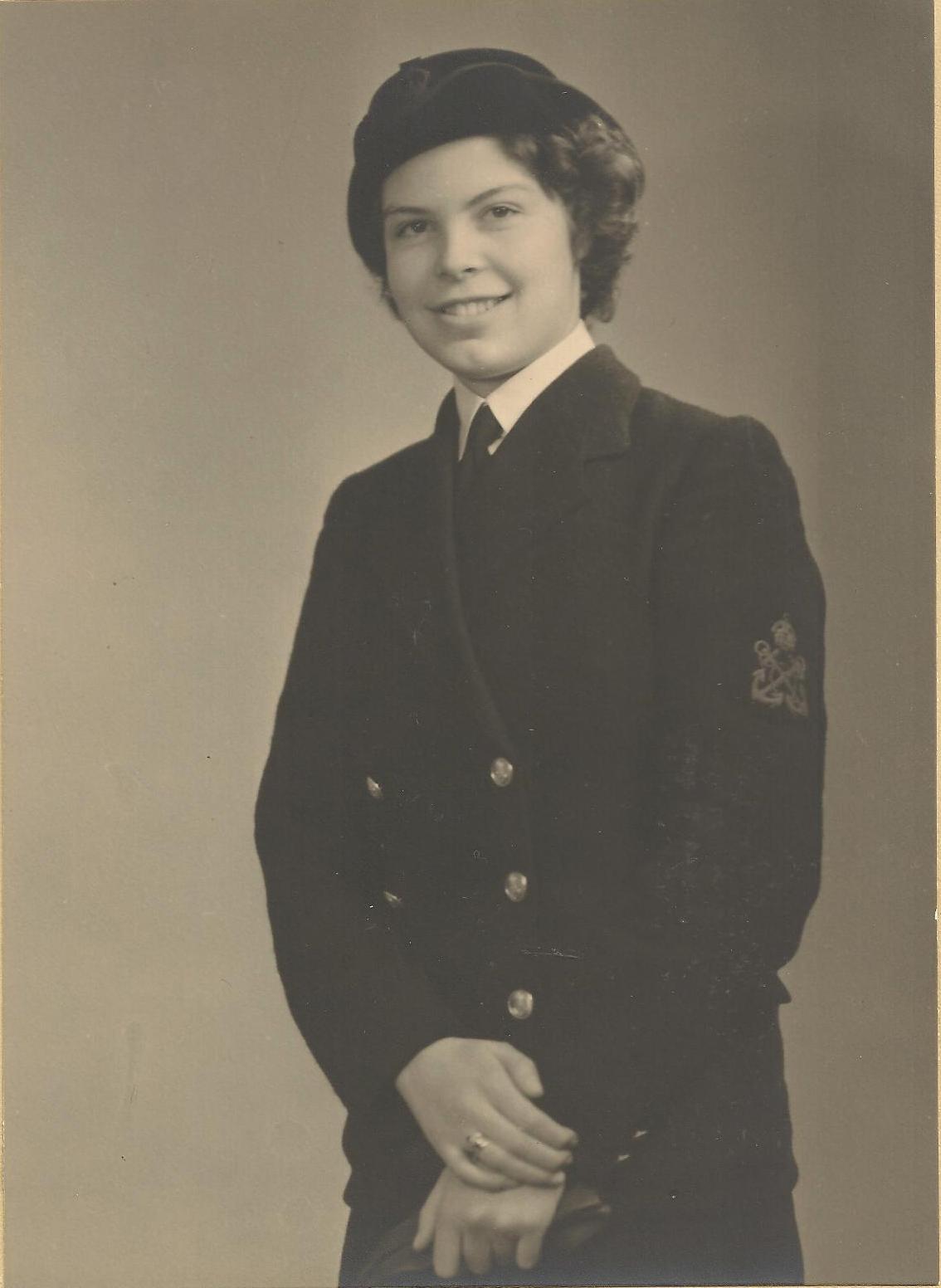

An hour’s very pleasant telephone conversation between Ellen and Lene, who very quickly were on first-name terms, led to a delightful visit to Ellen and her husband, Thore Branth. There, Ellen spoke in greater detail about her own and her brother Henrik’s experiences during the Second World War and showed us her study which contained a large and impressively well organized archive of personal papers from the time before, during and after the war. In addition to Ellen’s diaries, there were several hundred letters which she and Henrik had sent to each other from the time when he left home in Hampstead in 1941 to become a recruit in the British armed forces until he left the army in 1946 with the rank of major in the BAOR forces stationed in Berlin. It was particularly interesting that the collection consisted not only of his letters to her, but also hers to him, which he had kept and subsequently passed on to her some years before his death in 2010. (Unfortunately, Ellen’s first letters to Henrik from 1941 and his to her from 1946 are missing in the collection. In addition, there were her letters to and from their parents from 1943-45, when at the age of 18 to 20 she served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (the Wrens), along with a large number of other notes, documents and photographs. A recurring theme in our conversations with Ellen – espercially when we started to discuss the possibility of writing a book based on her correspondence with Henrik - was that sheseemed to be labouring under the misapprehension that, while her brother’s life had been interesting, there was nothing special about her own years of service as a Wren in intercept and direction-finding stations (“Y stations”) along the Channel coast. We totally disagreed – and still do. Henrik’s life at the front in North Africa may, at times, have been more uncomfortable, unhealthy and dangerous than Ellen’s in England – at El Alamein, he led his regiment through a minefield in the middle of the night and under fire, and he was just a few feet from death when a shell ripped one of his comrades’ head f. As a staff officer, he also played an important role in the 8th Army’s advance north through Italy. However, Ellen’s final posting at Abbotscliff was in an area on the coast between Dover and Folkestone that was under daily fire from German batteries across the Channel. In the summer and autumn of 1944, while on leave with her family in London, she lived, like everyone else in the city, in constant fear of V1 and V2 rocket attacks. Ellen’s work intercepting radio traffic from German motor torpedo boats and pinpointing their positions was highly specialised, and so secret that it was subject to the 30-year rule.

Henrik and Ellen’s stories are unique and individual, but they are also representative of many other British men and women at the time. Henrik was one of 210,500 officers to serve in the British Army during the war. Ellen was one of the millions of women whose efforts – as the recruitment posters proclaimed – freed up a man to serve at the front, and without whom the British war effort would have been impossible. Women served in all three wings of the armed forces, as well as a host of other uniformed corps and organisations, they worked in the war industry, agriculture and forestry, hospitals, in fact in virtually every part of British society, frequently filling roles that few imagined would ever be entrusted to women. The war disrupted everybody’s lives and put them under enormous strain, but it also opened up new and unique opportunities – especially for women.

Ellen and Henrik were also representative of the Danish volunteers who fought for the Allies, albeit with the significant difference that they were not just Danes in Britain, they felt both Danish and British. Unlike many other volunteers, they did not fight principally for Denmark, but for both their homelands. This dual loyalty, combined with their complete assimilation into British society, informed their view of the war and of events in occupied Denmark.

We may never have completely convinced Ellen that her story was just as interesting as her brother’s, but she did go along with the idea of a book based on their correspondence. She granted us full access not only to the letters she and Henrik sent to each other, but also to their correspondence with their parents, diary entries, photographs and numerous other documents and items. We found her faith in us deeply moving, just as we did when Henrik’s daughters later lent us their father’s letters to his parents.

The only concern Ellen expressed about the project was her reluctance to expose “the silly little girl I was back then”. We definitely do not see the Ellen of 1940–45 as “silly”, but as an earlier version of a person anybody should be proud to have been. Notwithstanding that opinion, we have, of course, respected her wish for privacy by using only selected parts of her diaries. For similar reasons, we have only had access to the parts of Henrik’s diaries that his daughters chose to make available to us.

We have only had access to those parts of Henrik’s diaries which his daughters have chosen to put at our disposal.

Ellen was 15 years old in August 1940, when she wrote: “Here in England, we are all prepared for an invasion by the Germans. I am not afraid, for I know we must win despite all the setbacks we have encountered.” Five years later, she emerged from the war as a young adult, scarred by stress and loss. In a letter to Henrik, she wrote that she found it hard to really feel anything or to become attached to anyone. Fortunately, she still had, as her discharge papers put it, “a bright mind and the ability to make the best out of any situation”.

In her letters and diary, Ellen comes over as a gifted and thoughtful young girl of a poetic bent, with a turn of phrase to match. She was driven by a resolute determination to do her bit for the war effort, like her beloved older brother, and in line with their parents’ wholehearted commitment to the Allied cause. The war gave the young Ellen the opportunity to play an independent, adult role and assume real responsibility. It also enabled her to meet people from parts of British society whom she would otherwise never have encountered. At first, the war was exciting. It afforded her the opportunity to discover the world – and herself. But the costs soon began to take their toll, with hard, stressful work often on night watch, constant relocation to new stations, and the accelerating loss of friends as they went missing in action or were killed. Ellen has since wondered if her nigh-constant infatuations (always platonic – “they were gentlemen, those Englishmen”) and generally highly charged emotional life was due to the war or just her age. In fact, the impression left by the letters, in which she describes her increasingly hectic social life, is of a generation partying in the full knowledge that each day could be their last. Or, as Ellen put it, “nobody knows who is coming back home from the war, so you might as well enjoy yourself while you can.” But then, suddenly, the war was over. Like the rest of their surviving fellow servicemen and women, Ellen and Henrik (now 20 and 24 years old) had to rebuild – or in Ellen’s case, build from scratch – their lives in a completely different world.

Henrik’s letters and diaries reflect a young man who found his feet in the army quite easily, who enjoyed the camaraderie and other pleasures offered by the life of a soldier. He wanted to do his new job well, and had both the courage and skill to do so. His combat exploits culminated three months after he arrived in North Africa, when he distinguished himself at the Battle of El Alamein. This was followed by a long, anti-climactic period of regrouping and dull military exercises. Henrik, a staff officer by then, enjoyed the beauty of Syria, the biblical sites and Cairo, but was frustrated by the lack of meaningful work. He made no attempt to conceal from Ellen that he sought solace in alcohol. His mood improved when he landed in Italy in 1944 and was assigned to a far more responsible role. On several occasions, he described the campaign in Italy as a “sideshow, albeit a quite useful one”, but he felt that he was really doing his bit.

In an interview in the Danish newspaper Berlingske Tidende in August 1945, Henrik was asked what he was in civilian life. He replied: “Nothing. I went straight from school to war.” In fact, he was working for Glen Line when the war broke out, but after four years as a soldier, three of them far away from England, he felt so completely removed from his old life that he was “nothing” outside of the army.

The book revolves around conversations between Henrik and Ellen – about the war, about everyday life in England and in the army, and not least about their thoughts, hopes, dreams, frustrations, what they missed and what they needed. We have supplemented their correspondence with a selection of Henrik’s letters to their parents (to whom he wrote more about the war and his work, but less personally and confidentially than he did to Ellen), their parents’ letters to Ellen and diary entries by their father, H.T. Karsten. We have tried to remain in the background as far as possible, but have inserted paragraphs and notes that expand on some of the topics in the original texts and put the protagonists’ experiences into a broader historical context. As both Ellen and Henrik were subject to military censorship, they were unable to say much about their actual work. Henrik’s movements in particular would be difficult to follow from the letters alone.

The material from the letters and diaries was so extensive (over 400 letters and diary entries by Ellen, Henrik and H.T. Karsten) that we had to select and abbreviate texts – not least to avoid the many repetitions that invariably arise when family members write to each other about the same period of their lives. The irregularity of the wartime postal service meant it was important for both sender and recipient to know which letters had arrived and when. We have almost consistently chosen to omit this information, as well as the often long and repetitive sign-offs. With few exceptions, we have decided not to insert explanatory notes about the large number of family members, friends, acquaintances, fellow service personnel, Danish and Norwegian volunteers, politicians etc. referred to in the letters. In the source list at the end of the book, we refer to books, websites, etc., that feature further information on some of these people. In order to let their voices speak as consistently and vividly as possible, we have chosen not to mark omitted words and paragraphs with “[...]”.

Henrik’s diary entries and his father’s Daily Notes were mostly written in English, whereas most of Ellen’s diary entries were written in Danish. Most of the letters were written in Danish with a sprinkling of English words and phrases. Abbreviations and some military terms, etc., are explained at the back of the book.

For the sake of simplicity, all of the texts are presented in chronological order, even if the irregularity of the postal service often meant that the parties’ letters were out of sync with each other.

Copenhagen, July, 2018

Thomas Harder & Lene Ewald Hesel

pp. 80-90 (October-November 1942)

31 October*

New plan ½ Nov. More preparations. All keyed up. [Henrik’s diary]

On 31 October, Lieutenant Colonel Farquhar received his orders: the purpose of the attack was once again to get X Corps through enemy lines. This would give Rommel no choice but to fight on open terrain, where the British forces’ superior manpower, equipment and firepower would destroy his armoured units, forcing him to use up his fuel reserves and disrupt his supply lines.

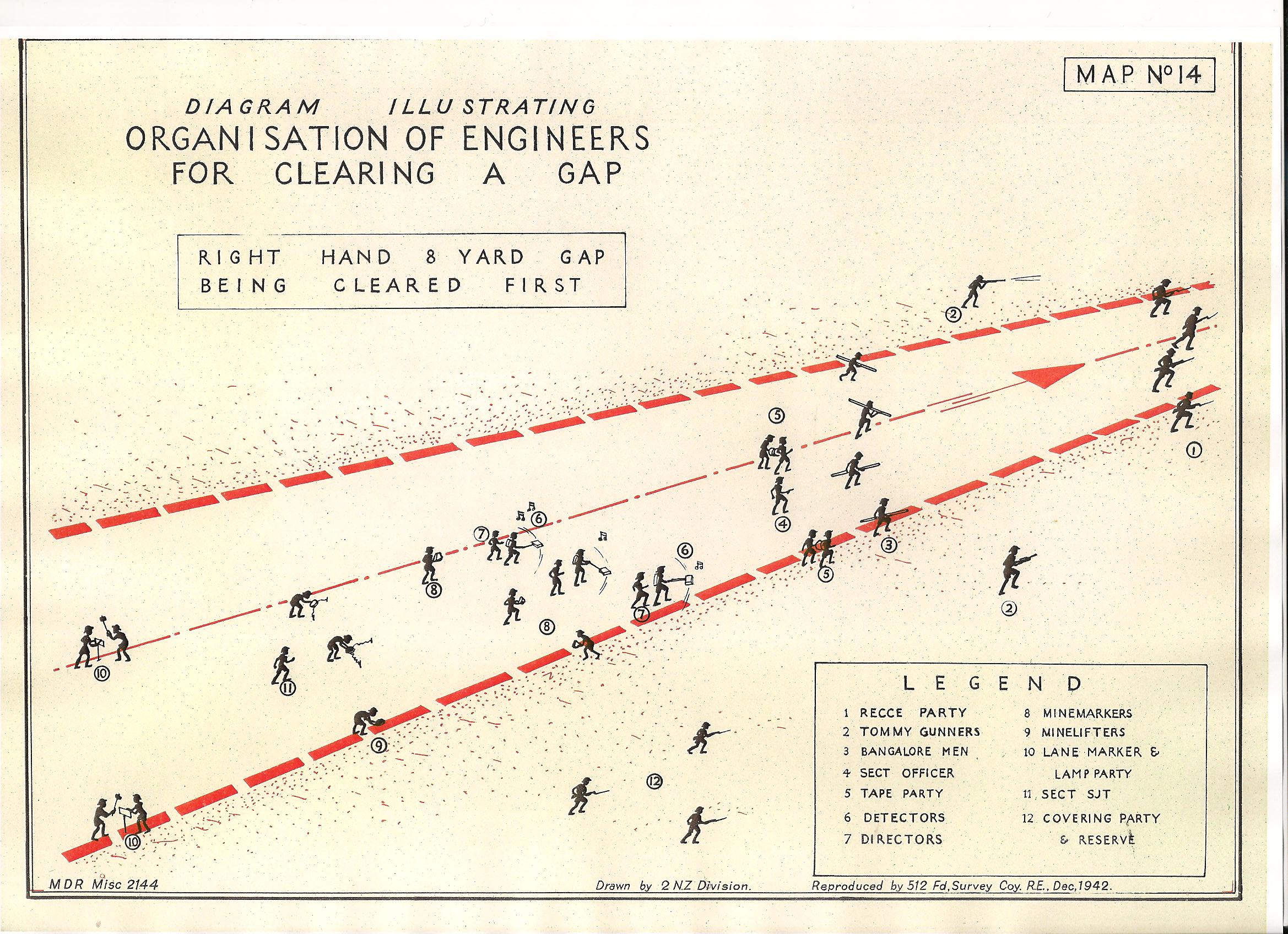

The attack began with an artillery barrage even fiercer than during Lightfoot. After this, two infantry brigades, supported by an armoured brigade equipped with Valentine and Matilda infantry tanks, were to fight their way through the German and Italian defensive positions while sappers cleared three paths through the minefields – one for each of the 9th Armoured Brigade’s three regiments: the 3rd Hussars, the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry and the Warwickshire Yeomanry. The infantry’s objective was to reach the Grafton Line, about 2 miles from their starting positions. The three armoured regiments were to meet there and advance another mile to the main road between Sidi Abdel Rahman on the coast and Tel el Aqqaqir, about 9 miles inland. Once this goal had been reached, the 9th Armoured Brigade was to “keep the door open” so that the 1st Armoured Division could pass through and engage Rommel’s reserves.

Montgomery stressed that “10 Corps must get through this time – otherwise the whole campaign may end in failure […] 9th Armd Bde must therefore reach their objective, whatever the cost, and, having got there, must hold it until the arrival of 1st Armd Div., even if this should involve 100% casualties.”[i]

My dearest Kek,

I expect you can understand that we are thinking of you in Egypt almost constantly - but we hope you are well. It is getting colder here now, and today we had a real fire for the first time. It is lovely, I must say. Yes, here at home the leaves have practically all gone, and it looks rather desolate.

Yesterday we went out to Waltham Cross where Christmas [Møller] was making a speech. We went because we thought it was our duty, for we had heard the same speech many times before. In the evening we went out to dinner with some Norwegians, all very charming.

Daddy has been re-elected to the Council and also to the Executive Committee. I went to an International Youth Meeting the other day. It was quite interesting. A Greek, Yugoslav, Pole, Czech spoke of their resp. countries. Jan Masmyk[ii] [1] presided. I have heard no more from the WRNS, but you know, I live in hope; one day I must hear. But I find typewriting and shorthand rather tedious. It takes time to learn.

1 November

Recce of route. Led Regiment into action positions. Very hard work and difficult. [Henrik’s diary]

At 20:30 on Friday 1 November, the 3rd Hussars left El Alamein, heading along the coastal road to the west. Several miles later, they swung southwest along Diamond Track, which led toward the front. The regiment was seriously weakened after incurring heavy losses during Operation Lightfoot: A Squadron consisted of only five tanks; B Squadron was in a little better shape with 11 tanks; while C Squadron was at almost full strength with 15. The Regimental Staff, where Henrik now served as intelligence officer, had four tanks and various vehicles, including Henrik’s Scout Car.[iii] So many officers had been lost during Lightfoot that two out of the three squadrons and most of the divisions were commanded by officers who were new to the regiment – many of whom had little experience with tanks. The much-diminished A Squadron replaced the regiment’s reconnaissance unit, which had been put out of action by losses and technical problems.

At 01:05 – following seven hours of air strikes against Tel el Aqqaqir and Sidi Abdel Rahman, and a four-and-a-half-hour artillery bombardment, during which 360 guns fired 15,000 shells at the German and Italian positions along a 2.5-mile front – the two infantry brigades attacked, advancing behind a barrage that slowly crept over the enemy positions. The attack proceeded largely as planned, and by 04:00 the infantry had fought its way to the Grafton Line. [iv]

The 9th Armoured Brigade rolled forward close behind the infantry, following the three 50-foot-wide tracks the sappers had cleared through minefields, marked with blue lights on each side. Driving at the head of the 3rd Hussars was Henrik, who had been appointed the regiment’s navigator, and Captain Richard Heseltine,[v] who led a unit comprising three tanks from A squadron. The regiment drove in a double column: tanks and other tracked vehicles to the left, wheeled vehicles to the right. Radio silence was the order of the day, but the darkness, the smoke from explosions and the dust stirred up by the vehicles was disorienting and made it hard for them to maintain contact by other means. It did not help that the compasses had been incorrectly mounted in some of the regiment’s new Sherman tanks – and even if they were working, the crews had not had enough time to learn to use them properly.

Shortly after the attack started, the 3rd Hussars came under heavy fire from enemy guns and mortars. The infantry company and anti-tank unit, which were to support the 3rd Hussars during the break out from the Grafton Line, were badly hit. As the tanks attempted to manoeuvre around destroyed and burning trucks, several of them collided or drove over mines.

The explosions blew out the blue marker lights, and Henrik and Heseltine had to leave their vehicles and traverse the darkness and the thickening haze of dust and smoke on foot to find a path through the minefield. While they were doing this, Heseltine’s tank was hit by a shell that blasted the engine’s air filters into three pieces, and would certainly have killed him if he had still been standing half out of the turret hatch, peering into the gloom. He wrote later: “Tanks and trucks ran on to mines and every single infantryman and gunner was eliminated: not one survived to get through. How Henry [Henrik] and I did is an absolute miracle.”

Henrik and Richard Heseltine eventually found their way through the minefield at around 03:20, and continued onward through the darkness and explosions – only to find, after travelling some distance, that nobody was following them. They had to go back and look for the rest of the men. Only once they had again made contact with the main force could they advance further and finally lead the 3rd Hussars out of the minefield.

Landmines, however, were still a serious threat. The idea was that sappers with mine detectors would walk in front of the tanks all the way from the minefield to the Grafton Line. A mine-clearing group usually consisted of about 20 men, three or four of whom worked the mine detectors, while the others removed the mines, marked the cleared lanes, etc. Only one sapper arrived until Heseltine’s reconnaissance unit reached the rendezvous point. He walked in front of Heseltine’s tank with his mine detector for a while, but progress was too slow. Farquhar’s orders were that the 3rd Hussars should be at Grafton by 05:00 to begin the attack on the enemy gun emplacements at 05:45, while it was still dark. Heseltine took a chance and decided to press on without waiting for mine clearance. It was a risky decision, but the 3rd Hussars arrived at Grafton at 04:50.

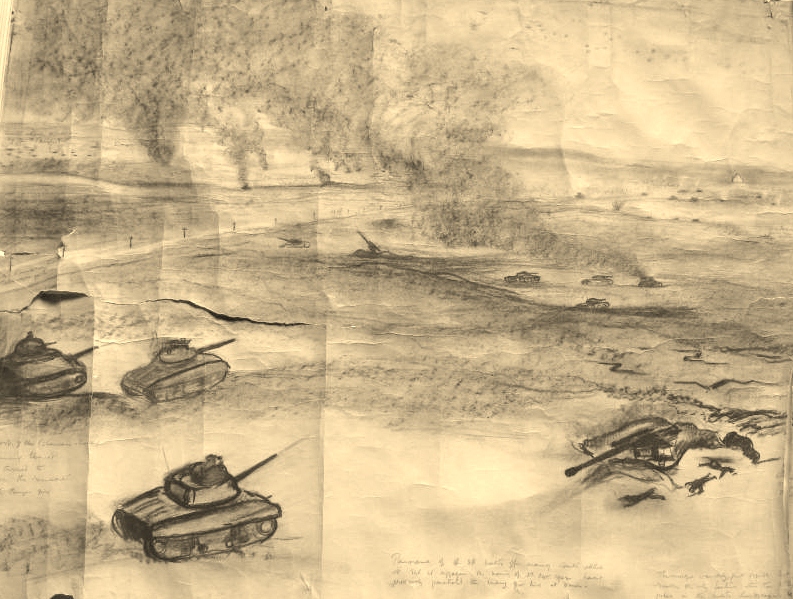

2 November*

Went with CO Tank as Adjudant away 0700 Very heavy fighting. God knows how I got out alive. I was expecting to be blown sky high any second. All day shelled. Heavy losses. Very few tanks left. Moved back slowly. Lots of prisoners. We held the gap. Did our job. Night simply heaven. Had no kit – in scout car. Slept just as I was. And well [Henrik’s diary]

Lieutenant Colonel Farquhar had been suffering from hepatitis for days. Shortly after the regiment had left the starting point, he collapsed. As Henrik had fulfilled his duties as navigator, he was appointed assistant adjutant and assigned to Farquhar’s tank – not a very comfortable workplace for someone standing 6’4” tall.

At 05:20, Farquhar received the message from brigade staff that “the Meet of the Grafton Hounds” was postponed for half an hour from 05:45 to 06:15, because the other two armoured regiments were delayed. The postponement from 31 October to 1 November and the waning moon had made it necessary to start at 01:00 instead of at midnight – they had lost an hour, but still had to reach Grafton before sunrise. They managed it, but the delay meant that the tanks would now be attacking the enemy as the sun rose. Launching a tank attack without infantry support against a line of anti-tank guns in well-prepared positions was tantamount to suicide, but no infantry were available, and “the door was to be kept open” – no matter the cost.

At 06:15 – half an hour before dawn and with visibility at about 300 feet – Lieutenant Colonel Farquhar ordered the 23 remaining tanks out of the original 35 to attack. To the left of the 3rd Hussars, the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry attacked, but the Warwickshire Yeomanry had not yet arrived. The creeping artillery barrage, at a speed of approximately 100 feet per minute, which was to pave the way for the attack, also failed to materialise. Despite all this, things went well for the first 4,000 feet or so. The 3rd Hussars took many prisoners, whom they left in their wake for others to pick up and take care of. By the time they reached the Rahman road, it was light enough for the tanks to be silhouetted against the eastern sky – perfect targets for anti-tank guns, which duly let rip at very close range. The German and Italian gunners had allowed the first tanks to pass and only opened fire when they were in their midst. The 3rd Hussars lost a dozen tanks during the first hour of battle. At one point, radio communications broke down, and for a while Lieutenant Colonel Farquhar only had five tanks at his disposal. Their commanders received orders by Farquhar and another officer walking back and forth between them and personally directing the battle.

Around 10:00, the 1st Armoured Division finally arrived. The remains of the 3rd Hussars helped them repulse a German counterattack, destroying five German tanks and an 88-mm gun. The regiment had already destroyed another 35 enemy guns that morning – in some cases, by driving over their positions and crushing both the guns and crews. “This was an adequate bag,” wrote Farquhar in his report. “We felt quite satisfied.”

Around 10:00, the 1st Armoured Division finally arrived. The remains of the 3rd Hussars helped them repulse a German counterattack, destroying five German tanks and an 88-mm gun. The regiment had already destroyed another 35 enemy guns that morning – in some cases, by driving over their positions and crushing both the guns and crews. “This was an adequate bag,” wrote Farquhar in his report. “We felt quite satisfied.”

Around noon, trucks arrived carrying food, ammunition and petrol. The 3rd Hussars, which by now had regrouped enough for Farquhar to have control of all eight surviving tanks, pulled back a little to resupply and let the men rest. Meanwhile, Farquhar met with the commander of the 9th Armoured Brigade, who ordered him to form a squadron from his eight tanks and temporarily serve under the command of the Warwickshire Yeomanry, which had just arrived. This improvised force saw action again later that day, destroying a German tank and a couple of 88-mm guns. As darkness began to fall, the remains of the 3rd Hussars withdrew a couple of miles to camp for the night. They then endured a five-minute and very precise enemy artillery attack, which Farquhar described as “bringing a particularly eventful day to a fitting conclusion”.

3 November*

Moved back after sitting in holding position all day. Still heavily shelled though more spasmodic. Had job of collating casualty figures. Very heavy. [Henrik’s diary]

The 3rd Hussars spent 3 November in a camp behind the front, occasionally exchanging fire, but incurring no losses at first. Lieutenant General Freyberg paid them a visit to congratulate Farquhar on the regiment’s exploits. At the end of the visit, the energetic Freyberg leapt into his car and disappeared in a cloud of dust, which attracted the attention of the German artillery. A shell destroyed one of the tracks of a Crusader tank and a lieutenant who was standing nearby was killed on the spot.

As intelligence officer and assistant adjutant, Henrik was one of those responsible for the regiment’s war diary. On 3 November, he recorded the regiment’s provisional losses during Supercharge: four officers dead or missing, two wounded (one seriously), and 60 NCOs and enlisted men dead, missing or wounded. According to a later account, the 3rd Hussars’ losses in the period 23 October–5 November amounted to 21 officers and 98 NCOs and enlisted men – approximately 80% of the men who took part in Lightfoot and Supercharge. These numbers include dead, wounded and “missing in action”. The ratio of “missing” was again disproportionally high.[vi]

During the afternoon, the regiment was ordered to hand over its tanks to the Warwickshire Yeomanry. They did so that evening, after which its remaining vehicles transported the men back to the train station at El Alamein. On 4–5 November, they travelled further east to Bay el Arab and Sidi Bishr on the outskirts of Alexandria. Later in the evening, Lieutenant Colonel Farquhar again met with the brigade commander, and it was agreed that the 3rd Hussars should be withdrawn from the campaign until new men and equipment were available.

4 November

Went to Bay el Arab on job. Very peaceful. Seems our job was well done. Jerry on run.

5 November*

Regiment back near Alamein. Went up forward to locate Brigade. No luck. Too far forward. Good news from the front Forward up by Matruh. [Henrik’s diary]

The breakthrough at El Alamein forced Rommel to pull back. During the withdrawal, British planes attacked the German/Italian forces and inflicted heavy losses. On 3 November, Rommel received an order from Hitler to hold the El Alamein position. Rommel obeyed. His forces stayed and fought for one more day but recommenced the withdrawal on 4 November, hoping to save what remained of his motorised forces. It was too late. In the next couple of days, the 8th Army took 30,000 prisoners and only gave up the chase when a violent rainstorm broke out on the evening of 6 November and rendered the terrain south of the coastal road impassable.

6 November

Slept near Alamein. Joined Regiment near Bay el Arab. Moving back to Sidi Bishr near Alex. [Henrik’s diary]

6 November

An ordinary kind of day in there. I live for 4:30 – especially on Fridays, because I don’t really like what I’m doing. But it’s absolutely wrong of me to be so ungrateful, especially considering the state of the world. [Ellen’s diary]

7 November

Camp routine life. [Henrik’s diary]

In between the daily notes on routine activities in camp and regrouping the scattered remnants of the 3rd Hussars, Henrik recorded a memorial service for the fallen in the regimental war diary, as well as the funerals with military honours at the Alexandria War Memorial Cemetery of two lieutenants, Johnson and du Pre, who had died from their wounds.

7 November

So, we have opened up a second front. At the same time as Monty’s armies are doing so well in Egypt, the Americans have landed in North Africa, Algiers, Oran, Casablanca, etc. It’s very exciting. We hope and have faith, but we still hold our breath for fear it might be a dream.

A young P/O Henriksen, who was in the EAC in Singapore and was torpedoed on the way here from Rhodesia and spent 8 days in a boat on the Atlantic, visited at the weekend, so we had a full house – quite cosy, but a bit of work for us. [Ellen’s diary]

10 November*

Sent on job to Brigade HQ and other places. Went first to Matruh, nearly to Sidi Bahrani. Very interesting. Lots of derelict enemy tanks and vehicles. [Henrik’s diary]

12 November

The main thing is that I’m alive, which is saying something since I have had a few far-from-fun experiences I can’t describe.

Tonight, I hope to sleep in pyjamas for the first time in a long, long time. I’ve had all my clothes brought up from Cairo, where I had left them.

As you can no doubt imagine, we are all in tremendous spirits out here. Morale is very high, everything is going well – it’s just a matter of how fast we can chase the Germans, many of whom I have seen dead recently, and have even been involved in firing on them. I have also seen lots of POWs, which is great. I hope you got the letter I wrote just before we went in. It is very strange, but I had no strong feelings before we attacked – I had enough to do just getting on with my job.

How’s everything at home? I thought of Daddy on the 5th. I haven’t received any letters for a few days, for obvious reasons, but should soon. I must say that I really like being in the desert. It’s a very simple life with a job to be done. I’m quite good at frying sausages, etc. It’s really not an art, but it’s good fun eating that way.

I’ve been out and bought some new clothes after mine were ruined by shrapnel, but I don’t think I have to pay for that.

I’ve just been out on a long drive, 450 miles, and am a bit exhausted, but it was a very interesting trip. The worst thing about it all is that I can tell you so little. Once I get home I’ll tell you the full story, but we did well. [Henrik to his parents]

14 November*

Sent on I.O. course at Helwan near Cairo. [Henrik’s diary]

British church bells had been silent since Dunkirk in May 1940, as they were to sound the alarm in the event of a German invasion. But on Sunday 15 November, they tolled across the land to celebrate the victory at El Alamein. Mass-Observation registered that after El Alamein and the almost simultaneous Allied landings in Morocco and Algeria, public optimism and interest in the daily news increased, war weariness receded and production in the war industry skyrocketed. Churchill said in a famous speech that victory had “warmed and cheered all our hearts”.

I rode my tank to Alamein

Prepared to do or die;

I led my few to victory

Now all I do is cry.

We the survivors did not raise our arms in salute to victory, as the historians would like us all to believe. On the contrary we behaved very differently. Alamein had a profound effect on us. I don’t think we were ever the same again. We knew we had achieved a great victory, but where were all those who had accomplished it? They would never be with us again. The old Regiment was gone; it was no more. For my part I marvelled at being left alive, but I was sorely distressed [...] We felt no glory: rather we felt sadness […].

Mike and I converged on Sir Peter, who was standing beside the jeep. I remember this so well. He was obviously very distressed. As we approached him he said to us. ”The Regiment must think me a butcher. I have destroyed the 3rd Hussars.”

“Oh, no, sir!” we both replied. “No one, not anyone, has ever thought that.

“But he was clearly very troubled indeed and we could not console him. [Richard Heseltine, Pippin’s Progress]

pp. 188-199 (May-July 1944)

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

25 May

It is so annoying when there is a shelling warning ... a rat-infested cellar is not the nicest place to spend the night.

I was very sorry to hear about Espelid.[vii] Four of my Norwegian friends are now gone ... But you know that even though I have my ups + downs, I enjoy life, spending time with other people and learning all the different things you only learn by having these ups + downs. If a shell should decide it would be nice to land here, rest assured that I thought it was good to be alive. [Ellen to her parents]

Abbotscliff was on the part of the Channel coast called Hellfire Corner, because it was within reach of the German gun batteries at Cap Gris Nez. Until the Canadians captured the batteries at the end of September 1944, 3,059 alarms sent people rushing to bomb shelters on the English coast. The German shells damaged 10,056 buildings and killed 216 people.

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

26 May

Dearest Kek,

I think I should write a letter and hopefully it will make a change for you. Everyone says that one should write to the troops. Not that anything special is happening. It is almost two, and when I finish my watch, I will have had one hour of sleep in the last 24 – but that is probably nothing new to you.

I haven’t even done anything special in those 24 hours: I went for a walk in the countryside, had tea at a farm; and then walked along the cliffs back to the house. I always reminds me of Wergeland‘s beautiful poem "Cliffs of Dover". The first verse goes:

That which glitters yonder west

‘Twixt the sea and skies above her,

That is England sun-caressed,

Lo, the cliffs of Dover![viii]

One day, when I was feeling a little lonely and depressed (probably because I hadn’t heard from Niels! [Danish RAF Flying Officer Niels Buchwald, photo below]), I sat on the rocks and learned it off by heart. In the evening, I had dinner with a Wren girlfriend in a dirty little restaurant where you get absolutely excellent food, which would even be acceptable in peacetime. I think it‘s a Swiss person who owns it. I was at a party the other day in civilian clothes, because ratings aren’t allowed in officers’ messes in uniform! Met an older, quite nice Canadian who said he had written a book called The Specialist. It’s about a man who built toilets – you know, outdoor ones. But I don’t really believe him.[ix] And because he was a bit difficile on the way home (my officer sat in front of us with the Padre), I was “out” when he phoned. It irks me that they think that because you talk to them and dance with them and even drink with them, that you also have to kiss them. I don’t want to (and don’t) kiss just anyone. I must say I have not yet had any "unfortunate“ offers the way that so many – almost all – of my pretty girlfriends have had. I am at a loss to know what has become of young people! Because there is a war on, they seem to think immorality can have free rein. (I’ve got my soap box out for Hyde Park!).

Undated, probably late May

Feeling totally cut off down here at the moment – from friends, family and real interests. This life in the Wrens, interesting and instructive (of life, I mean) though it may be, and apart from the fact that it is one’s duty and responsibility to do something for King and country, I feel that it is a life I only live with a small part of myself. [Ellen to her parents]

On 3 June, the 9th Armoured Brigade was at Frosinone, about 45 miles south of Rome. The next day, Henrik wrote in the Brigade war diary: “It is reported that the Americans have entered ROME this morning.” On 6 June: “The great news that everyone has been waiting for came this morning. The second front had started.” On 7 June, most of the Brigade passed through Rome and continued north. June and July were spent advancing laboriously through Central Italy. The Germans continued to alternate between skilfully conducted retreats and doggedly defending their positions. On 30 July, the 9th Armoured Brigade reached Perugia in Umbria.

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

5 June

Dearest Kek,

Mammie phoned the other day – very worried because she hadn’t heard from me. Niels called too, but I wasn’t allowed to talk to him because I was on watch. That was really annoying. They have become much stricter, and since we have highly irregular watches, I can’t tell people when to call. You have to send telegrams saying “I‘m in on such and such a day."

I miss Niels a lot. It‘s six weeks since I saw him, and there is no prospect of it happening again, as we have so many bans on this and that. I haven’t made it home in two months, and I‘m only 50 miles away. You feel so cruelly out of contact with your family, friends and real interests that I feel that only a small fraction of me is alive. This is just existing. I go out with some Canadians now and then, but nothing compares. Sad letter, but I will write a cheerier one soon.

Ellen’s letter of 5 June 1944 reflects not only the strict precautions imposed to keep the time and place of the imminent D-Day landings secret, but also how busy everybody was at that time. In early June, the station chief received sealed orders, which was taken as a sure sign that the invasion was imminent. In the listening stations, it was feared that the Germans would launch a counter-invasion or raids on the coast. The Wrens were told that if captured, they were only to state their name, rank and serial number..

6 June

Was awakened at 4 o’clock in the morning by Hilda Torrens Spence, who whispered: “Ellen, it‘s come, it‘s come, the invasion.” The vague, grey shapes in the early morning light, which I had expected would come, were like something from a dream. We got up and watched the small grey ships slowly sailing westward. It was said to be the second wave. God bless and protect all who sail in them. One‘s thoughts pound and slither. I/O received sealed orders, and they were all on watch, but rien, pas du tout. Later, we saw more ships (can’t say any more about that), and much to our dismay we saw one of them burst into flames. First flames and then an explosion, and it is still burning. Those poor souls, but we see so many strange things these days. The communiqués say it is Le Havre and Cherbourg. Eisenhower has issued the orders of the day, and Monty is over there. We get bulletins every hour, and everyone‘s mood is quite subdued. We are probably all thinking of our loved ones who are there. I myself feel a little distracted – and am greatly saddened that I have not managed to talk to him with whom my thoughts reside. God bless him and all the others. Oh, what joy there must be in Europe. God grant that all goes well. The explosion, oh! But the day has come. I think more will too. Rome fell yesterday. Nice. And without a fight in the city. And then Dunkirk Day on the 6th.

7 June

Progress is still being made, very slowly. Yesterday, 13,000 planes flew sorties. 4,000 ships and thousands of small boats also took part. It‘s so difficult to get your head around it all. Our forces are heading towards Caen. We see ships – and are forever being shelled – which is a bit tedious when you have been on and/or are about to go on night watch. I received a message from 501 and Garry [commander of 501 Fighter Squadron] that all is well. But Niels... Our telephone is hors de combat, which is doing nothing for morale! [Ellen’s diary]

Ellen and her friends also saw some huge, rectangular concrete structures being towed across the Channel. They later found out that these were some of the many Phoenix breakwaters that formed the basis of the temporary, mobile Mulberry harbours that were anchored at Omaha Beach (Mulberry A) and Arromanches (Mulberry B) to make it possible to land troops and supplies until the Allies controlled the French ports. The remains of Mulberry B, later renamed Port Winston, are still visible off Arromanches.

9 June

... and then the colossal, indescribable feeling of something much bigger than humanity that took place. I have seen things I would never have thought that I would see. [Ellen to her parents]

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

9 June

My dearest Kek,

Congratulations on Rome! We were amazed to hear that it had fallen without the Germans destroying as much as might have been expected of a “Kulturvolk", as they call themselves. It was a strange feeling to be woken up at 4 o‘clock on the morning of the invasion and be told that it had started. We went out on the cliffs to see what we could see, but that will have to be one of those things I tell you about when we all meet again. I was so glad I wasn’t asleep at zero hour. It meant I had a sense of what was going on.

I think of Niels a lot at the moment. There is no point in worrying. I haven’t heard from him for a while – and that doesn’t make it easier. Kjeld, my New Zealander and several other friends are probably there too – Peters‘ boys, you know. (I think I told you that Bunny is married now), and then, of course, I have you to be thinking of as well. It is so emotional to think about. It is what we have hoped for and dreamed about for so long, and it is finally starting to take shape. Slowly, but surely. I listened to a German broadcast to hear what they are thinking. The announcer began “Wir wissen Alle was los ist” [We all know what is going on] – Let‘s hope they understand that we are serious this time. We are shelled from time to time and have to wear our Tin Hats wherever we go. It feels a bit like wandering around with a shopping basket on one’s head.

11 June

It is Sunday morning. I am trying to listen to the radio from Denmark. There is a good sermon on, but the Germans are jamming it.

We are following everything that is going on, of course, with great excitement – it’s so strange to not actually notice that the invasion has started. Life goes quietly as usual here, while so many others fight for us. But that is just the way it is. Of course, there was a time when it was the civilian population who bore the brunt. [Elli Karsten to Ellen]

16 June

Thursday the 16th was the first night we had the pilotless planes. We didn’t know what the low humming sound was. They were met by plenty of anti-aircraft fire, and I saw one being shot down. We all went to the basement, of course, and I stayed there until it was my watch. Then we had a landing scare and the whole station sheltered in the watch room, which was pretty packed – it wasn’t easy to work with that many people buzzing about. A few nights before, we had a terrific shelling. I was in the tower, of course, but luckily I wasn’t afraid. [Ellen’s diary]

The first V1 struck London on 13 June 1944 and this new type of weapon was first mentioned in the British media on 16 June. “V” stood for Vergeltungswaffe (“vengeance” or “retaliation weapon”, because the Germans saw the rockets as a direct response to the Allied bombing of German cities. Due to their low humming sound and irregular flight patterns, the British quickly nicknamed them doodlebugs and buzz bombs.

Over the summer, the Germans fired over 10,000 V1 rockets at Britain. Of these, 7,488 made it further than the coast and 3,957 of them were shot down by anti-aircraft guns and RAF fighters. Of the remainder, a total of 2,420 hit London. At total of 6,184 people were killed and 17,981 injured. Thousands of Londoners left the city of their own accord and a new wave of evacuations was launched: by 1 September, over a million school-age children, mothers with children under five, pregnant women, sick and elderly people had been evacuated.

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone, 20 June

Dearest Kek,

Please forgive me for taking so long to write, but either I haven’t had the time, or else I haven’t had Air Letters handy when I did have the time – but I have just come off the night watch and am waiting my turn for the bathroom (we have only two between about 50 of us). After that, I might go into Folkestone for a coffee. A bad habit, but I enjoy it.

I don’t think I have written to you much since the invasion. It seems to be going very well, but who are we to judge as we get our news from the radio and the newspapers. It’s a very strange feeling that we just get on with the daily grind here, while out there, so close by, others are fighting so fiercely. We receive our share of small presents from the other side of the Channel, of course, but they really are so little by comparison.

Niels, I assume, is involved somewhere. Since he has an APO address now, I am unlikely to see him anytime soon. I haven’t had a letter for about a month and am a bit annoyed with him. But I don’t think it would be right to show it by retaliating in kind, so I still send small missives! I have to go now and take my bath while it is free.

Malheureusement, somebody skipped the queue – cheeky blighter, but I don’t really dare kick up a fuss and call whoever it was names in case it turns out to be my C.O.

Last night I was down in the Army Education Corps to speak French with the Sergeant Major who runs it. His French is fluent, and it was very pleasant. I find mine is so rusty. I presume you will be learning some Italian.

Fredrik Fearnley, one of my Norwegian friends who is dead now, once wrote that the only Italian he knew and found necessary was “Quanto costa una botteilla del vino” – but then again, he was a bit mad!

I am going out with some of the Canadians now and again. But to be honest Kek, I don’t much care for them. I like to drink, but not as the only thing to do – and I can’t stand uncouth stories – I grew out of that when I was at school!! Besides, one has to be careful not to encourage them, because one knows what they’re like, and I don’t want to neck (not just with any old bloke at any rate!!)

HQ 9th Armoured Brigade, CMF

23 June

Dearest Elle,

Today, it is two years since I landed in the ME, and it feels like several years. Two years is nothing really, and I quite enjoyed it, so no regrets. Life is a bit dull at the moment, and we all yearn to get it all over with. As long as things proceed fairly quickly in France, the war might be over soon. Italy is just a sideshow, but an important sideshow, nevertheless, because we are forcing the Germans to send not inconsiderable forces down here when they need them in so many other places.

I have certainly seen Italy, and it is a beautiful country, but you don’t really get to appreciate it when you’re in the army. We aren’t tourists after all, and I very rarely see a town, as we usually camp in fields.

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

27 June

Dearest Kek,

I think Mammie told you that Erik Kiær was killed on the first day in France and is buried on the beaches. It is so very sad, especially for you, dear Kek, as you were such good friends. He was also the one of Aunt Karen‘s children whom we knew best, for as long as I can remember. It feels like such a break with the past, but one gets so used to losing close friends.

Otherwise, my usual boring life drags on. Although I did have a nice surprise that will – and must – keep me going for a while. Niels sent a telegram to say he would come down to visit me – he had 24 hours free and was feeling very guilty, because he hadn’t written for so long! But he missed the train, and as the next one was much later, I said that I would meet him in Ashford, so we could have an hour longer. We only had 2½ hours together, but it was great to see him again. He looked well and has been busy although no “joy” as he doesn’t see much of the Germans. It’s so sad to say goodbye. I always get quite depressed, even though that doesn’t help. But two-and-a-half hours, after not seeing each other for two months! All we could get was bread and cheese, and I couldn’t find anywhere to sleep, although I did finally find some terrible place that I didn’t dare show him. He would have died of shock! I wasn’t exactly delighted either, but I had to sleep.

We have such fun with doodlebugs and buzz bombs, but they are being dealt with. Mammie doesn’t like the doodlebugs and sleeps downstairs. Then again, there seem to be significantly more of them in London. You lot are doing well in Italy and we often think about you. It is good that Cherbourg has fallen, and shows that the Americans can do their bit as well. I hear you are with Bob Larsen. Say hello to him from me.

Undated, probably June or July

Take care of yourselves – and look out for doodlebugs. I miss you. [Ellen to her parents]

1 July

We miss your short visits so much, but it is as well not to come here too often, it’s not healthy here. Your mother is a bit unnerved unfortunately and would like to get away ....

Things have really taken off in Denmark – and yet Denmark is still not considered a full Ally, which is such a shame for all those who are fighting over there. Many greetings to you, my girl, I hope the doodlebugs are not bothering you. [H.T. Karsten to Ellen]

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

3 July

Dearest Kek,

The weather is so awful. it’s pouring down, and since my job this morning involved running back and forth, you can probably imagine that I was a bit peeved. With just one exception, in April, we haven’t had a summer to speak of, and it’s particularly depressing when you think of the poor souls in Normandy. I don’t really know what it’s like where you are, but it ought to be good.

I think that I told you that I saw Niels for two lovely but far-too-short hours. I‘ve also been to an RAF party, which was very good. It was in Sir Phillip Sassoon‘s old house, which is very strange inside, but is in a beautiful location with a lovely garden. I met a lot of nice people, but even if they get your phone number (usually the wrong one so late at night!), you seldom see them again. You can bet I was delighted to be getting up again for a watch at 03:15 the next day. Ugh!

I just heard from Mrs. Peters and from Bunny‘s wife that he is in France. He is a doctor and with the Canadians. They are a bit worried because it’s been a long time since they‘ve heard from him. Most of my fellow Wrens here have friends or husbands either in France or in Italy, some even in Burma. We are all grass widows.

I hope you are hearing from Margaret regularly and that all is well with her. I think it‘s a long time since you have written to me, but even Mammie isn’t receiving letters from you right now. I often think of you, my dear Kek, and even though I try to imagine you as you are now, you usually look like a little boy in shorts in Rågeleje.

They are doing a good job in Denmark.

3 July

Your father is firewatching tonight. So they are protecting me. They had a bad time of it last night, with constant doodlebugs all the time, so I did not sleep much. Today, we have had warnings all day, and the weather is depressing, rain and yet more rain – Quisling weather. Life in London has changed: nobody goes into the city unless they have to – cinemas and buses are nowhere near as full as usual. [Elli Karsten to Ellen]

HQ 9th Armoured Brigade, CMF

9 July

Dear Elle,

I’m so glad you are fine, even though you don’t get home so often. Your experiences with the different men you meet are funny, but you’re quite right: men are hideous creatures, and not always moral and so on. But you seem to be able to take care of yourself.

I’m fine. We are billeted in houses now. We drive up to a nice one and just commandeer it. Usually, it isn’t a problem and the residents are very friendly and ply us with vino bianco. The first house was lovely, very modern and comfortable with a pink bathroom. We had a sitting room to ourselves, and I have rarely been so comfortable. It was owned by an English/Italian man married to a Norwegian lady, so I spoke a bit of Danish. In the next one, I had an actual bed to sleep in. Later on, we were just about to move into another house when Jerry started to shell it. We thought that was a bit much of them and camped out in a field instead. We’re in a house again now, an old one, but a house nonetheless. I don’t know who it belongs to, but it doesn’t really matter.

Otherwise, I’ve been pretty busy recently, and am really tired by the evening. We all drink our quantum of the local wine – there is nothing else, as my monthly ration of ½ bottle of whisky and gin is long gone. The wine isn’t too bad, a bit young and bitter at times, but there’s plenty of it, so we buy lots and usually only pay about 10 shillings a month, so it costs next to nothing.

The war is going well, I think. Perhaps it will be over before the end of winter. I hope so anyway. Progress here is slow but it is so easy for the Germans – what with all the mountains and them blowing up every bridge as they retreat.

8 or 9 July

Felt a little sentimental while reading Michael Drayton’s The Parting.[1] Mercy had some philosophical observations about meeting real people. [Ellen’s diary]

[1] The sonnet reads in full:

Since there’s no help, come, let us kiss and part,

Nay, I have done, you get no more of me,

And I am glad, yea, glad with all my heart,

That thus so cleanly I myself can free.

Shake hands for ever, cancel all our vows,

And when we meet at any time again

Be it not seen in either of our brows

That we one jot of former love retain.

Now at the last gasp of Love’s latest breath,

When, his pulse failing, Passion speech- less lies,

When Faith is kneeling by his bed of death,

And Innocence is closing up his eyes,

Now, if thou wouldst, when all have giv’n him over,

From death to life thou might’st him yet recover.

Abbotscliff House, Folkestone

9 July

Dearest Kek,

You will probably be a bit surprised to hear that the house – our home – was hit by a doodlebug. Apparently it struck at 21:15 on Friday the 6th. Fortunately, it landed on Hart’s small shed. The houses on both sides had to be demolished and our nice, quiet street looks a bit forlorn. Our house lost doors, windows and roof tiles. Aunty’s painting with the soldier has a tear in it but otherwise little damage was done – only the sides of the bathtubs, the oddest things. Mammie and Daddy are obviously a bit anxious and didn’t want to tell you, but I know how mad I was that they didn’t tell me quickly enough (I thought). They are all sleeping in the funkhole every night and, like during the Blitz, Aunt Lillemor and Peter are there too. I had to sleep between Mammie and the edge of Daddy‘s bed, but in spite of everything, it was great to see them again. As well as Aunt Lillemor and Peter, we had two other guests for lunch the next day.

Kek, I‘m in a bit of a daze at the moment, because despite Niels and all my other interests, I have met a man who is so definitely a kindred spirit – and the feeling is mutual. But curse my luck, he has to be married and have two children. I‘m not unhappy (!!), because it was so good to meet somebody so absolutely right, and so good to find out what the right thing is like. Now I know that everything else – no matter how nice – will never be anything like the real thing. But we have decided for the sake of everyone concerned that it has to be Ave atque vale [hello and goodbye]. This sounds a bit confused, and I am. But it hurts a little when you meet someone so marvellous and he’s already married!

17 July

It was so sad to hear about Erik, and totally out of the blue. He was always a good friend of mine. Give Aunt Karen my love. It is not easy out here either; some of my friends have also been killed, but you see and hear so much at war, perhaps it no longer makes the impression it should. But it is still terribly sad. [Henrik to his parents]

[i] Report on the action fought by 3rd Hussars Regimental Group in area NE of TEL EL AQQAQIR on 2nd November 1942. WO 169-4483.

[ii] Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of the Czech government in exile.

[iii] A squadron: 5 Crusader tanks. B squadron: 7 Shermans, 3 Grants and one Crusader. C Squadron: 7 Shermans, 7 Grants and one Crusader. Staff Squadron: 3 Grants, one Crusader.

[iv] Grafton is a hunt in Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire. The sources give no explanation as to why this name was chosen. Perhaps the cavalry regiments’ fox-hunting traditions and Sir Peter’s reputation as a hunter and “Master of the Foxhounds” played a role. Or perhaps it was to do with the fact that the British were hunting Rommel, who was known as the “Desert Fox”.

[v] Heseltine, who was a horticulturalist and artist in civilian life, had returned to the regiment on 30 October after serving with a special unit whose job was to camouflage the preparations for the offensive using all sorts of creative techniques. Heseltine had not been in a tank for seven-and-a-half months, but he was renowned for his uncanny ability to navigate through the desert.

[vi] The casualty figures are reproduced from Hector Bolitho’s regimental history The Galloping Third (1963) and Richard Heseltine’s memoirs Pippin’s Progress (2001). The numbers in Lt. Col. Farquhar’s report (presumably compiled by Henrik) are somewhat lower – 93 in total – but reflect the same ratio of dead and wounded to missing.

[vii] Halldor Espelid (6 October 1920 – 29 March 1944), known as "Harold", Norwegian fighter pilot; shot down on 27 August 1942 and taken prisoner by the Germans; participated in the 'Great Escape' from Stalag Luft III in March 1944; re-captured and shot by the Gestapo.

[viii] https://archive.org/stream/cu31924028465684/cu31924028465684_djvu.txt

[ix] Ellen was right to be skeptical. The author of the bestseller The Specialist, the American variety artist Charles Shine, died in 1936. Unless, of course, the “nice Canadian man” was one of the two journalists who helped Shine turn his variety monologues into a book.