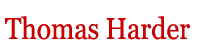

Order Special Forces Hero directly from Pen & Sword Books

Anders Lassen-thessaloniki, October-November 1944

Anders Lassen - From Opertion Postmaster to Comacchio

A short talk obout Anders Lassen on Crete - Operation Albumen - SENFORCE

There is such a thing as a ”natural soldier”: the kind who derives his greatest satisfaction from male companionship, from excitement, and from the conquering of physical obstacles. He doesn’t want to kill people as such, but he will have no objections if it occurs within a moral framework that gives him justification – like war – and if it is the price of gaining admission to the kind of environment he craves.

Whether such men are born or made, I do not know, but most of the end up in armies (and many move on again to become mercenaries, because regular army life in peacetime is too routine and boring).

(Gwynne Dyer: War)

A moonless night. Eighteen British soldiers and two Italian fishermen are crossing a huge lake. The soldiers row their storm boats as silently as possible. Their Italian helpers punt their long, flat-bottomed boat through the shallow, cloudy water.

The soldiers have spent most of the day lying in muddy holes on a small, flat, mosquito-infected island. Anybody who stood up would be visible from the observation post in the church tower on the opposite side of the lake, and draw fire from the German 88-mm guns.

Under cover of darkness, they complete the five-mile crossing to the bank occupied by the Germans. Most of the men are veterans of numerous landing operations, but they have never before seen a battlefield quite like this.

Commanding the patrol is a 24-year-old Dane. In a few hours, it will be exactly five years since the Germans occupied his homeland. He has been at war ever since.

Foreword

Anders Lassen was very young when his war began in 1940. He was still young when he died in action five years later. He became an adult during that time, and the war allowed him to express himself. Fervently patriotic, Lassen fought for his country – but he also had a strong desire to prove his own worth. War presented challenges that he could face on his own and with honour. Although not greatly enamoured by life at sea, he loved “the feeling of sole responsibility – when you zigzag in a convoy – and feel the ship obey you and you get to steer her as hard as you want [...] and the Skipper and Mate [... ] don’t bother you at all but let you get on with your job.”

Anders Lassen did not want to be a soldier, but became one because he felt it was the right thing to do. He was highly decorated, receiving the Military Cross three times for gallantry in action. He was also awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, the highest award for valour presented by the British Army. His courage, spirit of self-sacrifice, strength and military skills were legendary. In death, he has become an almost mythical figure. But he was also a human being, a man of flesh and blood. Like everyone else, he was the product of his family, his childhood and the people he encountered during his formative years. Although in many respects he thrived in wartime, it also wore him down. He was a historic figure, and his movements, actions and life can, to a certain extent, be reconstructed from various sources. This book attempts to do just that. It also seeks to put his life and military career into a wider historical context.

I have endeavoured to get under the skin of the man, as far as the sources permit, but still have much to learn about him and his war. I have not sought to fill these gaps with fictitious accounts, and where I do resort to speculation, assumptions or hypotheses, I make this explicitly clear.

Whenever I quote from sources in English, I retain the spelling and standards of the original. Every effort has also been made to preserve Lassen’s somewhat idiosyncratic style and spelling, including in quotes from his letters and journals, so these may differ somewhat from contemporary norms and expectations. Translations of sources in other languages conform with modern English standards, norms and spelling conventions.

Copenhagen, 22 January 2021

Thomas Harder

Introduction – 9 April 1940

Anders Lassen’s war began on the morning of 9 April 1940, when news that the Germans had occupied Denmark reached the tanker Eleonora Mærsk in the Persian Gulf. At the time, he had been at sea in wartime conditions for seven months, but the war declared by Britain and France on Germany on 3 September 1939 had not been his war.

He thought about volunteering to fight for the Finns in the Winter War with the Soviet Union in November 1939, but that probably had more to do with frustration and boredom with life on board the tanker, and a lack of interest in a career as a ship’s officer, rather than ideology or an actual lust for war and the military life. He was tempted to prospect for gold in Brazil, and emigrating to the United States also crossed his mind. Both options required seed capital, and Lassen welcomed the war supplement – 250% of the standard rate – that allowed him to save up and enjoy life at sea and in port. He was annoyed when Eleonora Mærsk was sent to waters not classified as war zones and he had to smoke a pipe or roll-ups instead of cigars, and drink beer instead of brandy.

Then Germany occupied his homeland – and for Anders Lassen, the world war suddenly became a personal matter.

[…]

Symi, 17 September–7 October 1943

On 13 September, Lassen was promoted to acting captain. He was also head of the Irish Patrol, which included three big, heavy-drinking scrappers: Sergeant Sean O’Reilly, Corporal D’Arcy and former gymnastics instructor Patsy “the Brown Body” Henderson, all three of whom had served in the Irish Guards but were none too enamoured of its rigid discipline. O’Reilly became a particularly close friend of Lassen. Assigning the men to patrols with similar backgrounds (the Irish patrol, the Guard’s patrol, etc.) was an informal means of encouraging solidarity within the patrols and competition between them. When the Englishman Hank Hancock was assigned to the Irish patrol, his comrades didn’t speak to him for the first three months.

[1]

The Irish patrol were, in Lapraik’s words, “an incredible collection of bandits”, but they “worked very well” under Lassen’s command. Concerning Lassen’s abilities as an officer, Lapraik said:

Some people found him a little bit trying and insubordinate, but I got on with him very well. Most of the officers and pretty well all the sergeants would have followed him anywhere because he knew his job.

However, not all of the officers shared his admiration:

They had the idea that Andy was a pirate, which was very far from the truth. […] Andy […] could have commanded a battalion. […] He didn’t need to be told.

[2]

*

On the evening of Friday 17 September, Lapraik and his men arrived on Symi. The noise of the ship’s engine caused great consternation on the island, where people thought it was a plane and that an air raid was imminent. When the ship came into view, as a dark shadow behind the headland off Symi town, the Italian forces on the island fired a warning shot that made the skipper slightly change course. Lapraik put a few boats into the water and sent Lassen and former boxing champion Doug Pomford to the quay to explain to the Italians that they were not Germans. Once that had been cleared up, the newcomers were well received by the Italian officers. The rest of the force could not come ashore until it was ascertained whether the harbour was deep enough for the ship to dock safely. No one seemed to know exactly how deep the harbour basin was, so Lassen dived in to find out. Once the depth had been measured and deemed adequate, the ship docked and Lapraik and his men landed. The ship set sail again shortly afterwards to avoid being seen in open water in daylight and present an easy target for the Germans, who still ruled the skies.

The Greek inhabitants rejoiced at the arrival of the British. The head of the Italian school system on Symi, Maria Luisa Caporali Cavallari, said that some of the British and the Greeks seemed to know each other from previous nocturnal visits, when local families had sheltered British agents. She also noted that the British soldiers were well-armed, well-supplied with provisions, well-disciplined and always preoccupied with their duties:

[...] no aimlessly wandering about, no wooing women.

The residents noticed the difference between the discipline of the British and Italian troops.

The Italian officers who had so warmly greeted the British officers, were somewhat ill at ease with their reserved and cool behaviour.

The same applied to our troops, [...] with whom the English would not enter into any form of comradely relations. The two groups lived side by side, but deeply separated.

[3]

The somewhat chilly relationship between the British and Italians did not prevent them working together on the island’s defences. Lapraik and the two Italian officers who shared command on Symi, Lieutenant Andrea Occhipinti and Lieutenant Commander Corrado Corradini (a former port commander in Rhodes wanted by the Germans for his anti-German attitude), were willing to do their best to hold the 26-square-mile island. Occhipinti and Corradini had at their disposal a machine-gun company, two 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, some carabinieri and members of the military customs corps Guardia di Finanza.

[4]

The Italian Navy also had a lookout post on the island and the harbour commander had his own staff. Symi’s Italian garrison numbered approximately 150, bolstered by around the same number of soldiers and sailors who had fled to the island from Rhodes. Occhipinti had been promised 200 men from the Italian naval force on Leros, but they never arrived. Nor did Lapraik’s force receive any reinforcements, although he asked for them and stressed that Symi was crucial to operations on Rhodes.

[5]

Corradini moved the Italian forces from Buormiti and Dracunda, near Symi town, to various high points from where the most obvious landing places along the coast might be covered. On 13 September, General Mario Soldarelli on Samos, who had assumed command of the Italian forces in the Aegean Sea after the fall of Rhodes, ordered Occhipinti to mount the strongest possible defence of Symi against German attempts to land. By this point, the lieutenant had already made great efforts to strengthen his positions and prepare his men.

[6]

On 25 September the Levant Schooner LS Hedgehog arrived in the port of Symi carrying a party of six men of the LRDG commanded by Captain A.G. Redfern.

Redfern, who was born in 1906 in Harare, Mashonaland East, Southern Rhodesia, had been a civil servant, hunter and wildlife photographer before the war. When war broke out he volunteered for service and received a commission in the newly formed Rhodesian African Rifles in 1940. At a time when an Axis invasion of Southern Africa was considered a real possibility he was put in charge of training men for commando and guerrilla warfare (much as Lassen had been in Nigeria). Many of his trainees joined the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa, as did Redfern himself; as temporary captain he was appointed OC of the LRDG’s S1 Patrol.

After liaising with Lapraik, Redfern and his men sailed on, this time in a local caique, to the large St. Michael monastery in the village of Panormitis on the west side of the island. After some initial confusion during which the LRDG party was fired on by Italian troops, without sustaining losses, Redfern and his men were received by the monastery’s abbot, who had the church bells peal in their honour and placed the monastery at their complete disposal. Redfern also met with the Italian lieutenant whose men had fired on him and who was now ‘most apologetic and all out to please’.

The monastery’s abbot, Chrysanthos Maroulakis, was a very active member of the local resistance movement. His activities had included helping the SOE smuggle agents into and out of Rhodes and hiding Italian deserters. After the SBS occupied Symi, the abbot had worked with both Lapraik’s people and with his SOE contacts, who in turn worked in parallel with and independently of SBS. The abbot hid weapons, radio equipment, food and personnel in his monastery.329 He now assisted Redfern’s party in setting up an observation post with a wireless set on a hill approximately 45 minutes climb from the monastery from where Redfern’s men could monitor the narrow strait between Rhodes and Turkey and report on sea and air traffic to and from Rhodes, Kos, and Leros.

[7]

The British were primarily interested in Symi because of its proximity to Rhodes, which they regarded as the key to the Aegean. From Symi, it was relatively easy to smuggle agents into and out of Rhodes, where they could spy on the Germans and make contact with local resistance fighters and SOE agents. From Symi, the highest point on which was 2,000 feet above sea level, it was also possible to monitor the narrow strait between Rhodes and Turkey and traffic to and from Kos and Leros. Had the Germans occupied the island, it would have been more difficult for the British to maintain the link between the Aegean and their bases in the Middle East and Cyprus through Kastellorizo. Symi was also a good starting point for expeditions to the islands of Halki, Alimnia, Nisyros and Tilos between Rhodes and Kos.

Unable to count on reinforcements or air support, Lapraik had to rely on the Germans’ lack of interest in Symi or the German forces on Rhodes not having the resources to take on his British/Italian garrison. Despite Corradini and Occhipinti’s professions of goodwill, Lapraik did not know how fiercely their men would fight against the Germans if it came to it. He also feared that the Italians’ poor relations with the islanders might pose a problem.

Lapraik, a lawyer by profession, took it upon himself to govern Symi. He sought to prevent clashes between the Greek population, emboldened by the British presence, and the deeply unpopular Italians. A couple of incidents arose when Greeks and a few British soldiers refused to stand during the evening ceremony when the Italian flag over the harbour commander’s office was lowered. The Italian carabinieri arrested four Greeks and complained about the British to Lapraik. Soon, around 70 Greeks had congregated in front of the British command post, demanding guns to kill the Italians. Lapraik explained in no uncertain terms to the angry Greeks that their island was still under Italian sovereignty, and as such they had to show respect for the flag and to obey its representatives. At the same time, he also made it clear to the Italians that they should not insist that civilians solemnly salute their flag. To avoid further incidents, Lapraik ordered that, every morning and evening, the British flag should be raised and lowered alongside the Italian one, and urged local people to attend the joint ceremony. When a drunken SOE-officer shot portraits of the Italian royal couple on the wall of a taverna one evening, Lapraik deported the culprit to Kos right away.

[8]

Once Lapraik had made it clear to all three parties that trouble would not be tolerated on the small island, a period of relative calm ensued. He left the civilian administration to another officer and focused instead on what he had come to Symi to do.

[…]

Symi, 7 October–2 November 1943

On 6 October, a contingent of 45 men – ground personnel, medical orderlies, an RAF doctor and reserve pilots from the South African Air Force (SAAF) – arrived on Symi. The doctor, Lieutenant Leslie Ferris, and his assistants took over a house near Lapraik’s command post in the middle of the town and set up a makeshift infirmary to receive people injured and wounded in fighting or air raids. Ferris immediately began examining two SBS men who appeared to be suffering from malaria, and Lassen’s extensive burns.

[9]

The newcomers were placed on sentry duty that night. Lassen and his patrol seized the opportunity to get a proper night’s sleep before they were to embark on an expedition to Rhodes the next day.

The SBS was not the only force to conduct raids in the Aegean. The same morning, at 02:30, the German Sturm-Division Rhodos received a telephone call from Army Group E’s headquarters in Salonika. The commander of the Army Group, Colonel General Löhr, who was in command of German, Bulgarian and Mussolini-faithful Italian forces throughout Greece, ordered “immediate clarification of the situation on Symi”, which the Germans knew was a base for spying on Rhodes. At 08:00, the commander of Sturm-Division Rhodos, Lieutenant General Kleemann, met with half a dozen key officers from his division and the Kriegsmarine. Half an hour later, he gave the order to launch Unternehmen Trianda.

The operation involved landing a “pirate detachment” on Symi to locate and destroy a radio station the Germans suspected was on the island. (This may have been the transmitter that Lassen had helped to establish in the Panormitis Monastery, another that Lapraik used to communicate with Kastellorizo, or perhaps one that the SOE had set up on the island befre Lapraik arrived.) Any enemy combatants they encountered were to be captured or killed. The whole operation was to last no more than three hours. When it was finished, the force was to withdraw, continue to Nisyros, 30 miles due west of Symi, and carry out a similar operation there.

[10]

At 04:00 on Thursday 7 October, the 120-ton caique Esperia, with the motorboat Parma in tow, sailed into the long, narrow Pedi Bay, approximately one mile east of Symi town. On board were 59 men (of which 17 were sailors, wireless operators, interpreters and other more or less non-combatants) some of whom had volunteered for an operation with an unknown target and purpose, under the command of First Lieutenant Fresemann from Grenadier Regiment Rhodos. Fresemann and his men had set sail from Rhodes at 21:45 on Wednesday evening. They now sailed unchallenged into the bay. Esperia dropped anchor about 200 feet from shore. At 04:25, Parma brought the first group ashore at a small fishing village at the westernmost end of the bay. It was already light, the sky was clear and it promised to be a hot day.

Pedi Bay opened up to the sea to the east. North and south of the bay were steep, barren hillsides. However, to the west, the landscape was relatively flat and open, rising gradually up towards Symi town, the highest points of which were 200–300 feet above sea level. A dirt road ran from the fishing village up towards Symi, passing through vineyards and scattered houses.

As the Germans came ashore, curious locals greeted them with a surprisingly cheery, English “Good morning!” They told them that all of the soldiers had left Symi (in recent days, there had been a lot of traffic back and forth with men and supplies, which had given many locals the impression that the British and Italian forces were evacuating)

[11]

and they knew nothing of any radio transmitter. However, the Germans had caught sight of a tall mast on top of a citadel-like building on the outskirts of the town, which they thought might be the antenna.

[12]

*

With a Greek as a reluctant guide, the Germans headed towards the town. At 05:20, the two German groups at the front – each comprising approximately ten men – came under heavy fire from (as far as Lieutenant Fresemann could make out) four 20-mm anti-aircraft guns and ten light and heavy machine guns, located in a row of old windmills on a ridge at the edge of the town. Part of the Italian garrison had taken up position there.

The Germans returned fire immediately. Fresemann sent a runner back to the main body with an order to send a group north of the windmills to attack from the rear. The runner never arrived, but a dynamic NCO, on his own initiative, launched the attack anyway. This forced the Italians to retreat westward, into Symi and upward into the high part of the terraced town.

The battle raged from house to house and from gateway to courtyard. The labyrinth of narrow, steep streets made it difficult to maintain an overview of the whole battlefield. The fighting dissolved into a series of clashes between small groups of often only two or three men. The Germans almost reached the citadel on the city’s eastern edge, but could not make it past the 50–60-foot-high walls, and were driven back by machine-gun fire and hand grenades.

Just after 08:00, as fighting raged in the town, the 20-mm guns around Symi – especially from the tall citadel, and most likely Lassen’s cannon – opened fire on Esperia. The caique was forced to leave Pedi Bay and wait in open water, covering the foothills along the mouth of the bay.

At 11:15 – after six hours of continuous combat – Lieutenant Fresemann pulled his men out of the town. They were exhausted, weakened by heat and thirst (although the locals gave them water after they banged for long enough on the closed doors and shutters), and running out of ammunition. Fresemann had no more reserves to deploy, and had lost faith in the reinforcements and air support promised to him from Rhodes. He feared that his retreat would be cut off by British and Italian forces advancing from other parts of the island. He ordered his men to retreat to a bridgehead at Pedi Bay and Muglia mountain, which formed a peninsula along the north side of the bay.

The SBS and Italians harried the Germans as they withdrew. Some of the Italians fought under Lassen, who had seized command from the Italian lieutenant – who in his opinion showed insufficient gumption. Lassen led the attack, and his example encouraged the faltering Italian soldiers to follow.

[13]

Despite his dysentery and burns, Lassen’s lead made an impression on his companions. They later described his inexhaustible energy and ability to “be everywhere”, instinctively “read” his surroundings, sense where danger lurked, and move quickly and quietly. Lapraik said of him:

He had a natural eye for ground, for fire, for movement. […] He was what he was fortuitously. All the elements of a first-class soldier and very quick-thinking [...] I’d never known Andy hold fire. It could be said he was a killing-machine; you stayed alive if you became that.

[14]

Lassen’s actions on Symi earned him his third Military Cross. The citation gave Lassen much of the credit for the fact that the Germans were driven back – the British did not know that the Germans were not there to occupy the island – and stated that he stalked at least three Germans and killed them “at the closest range” – which may be a euphemistic way of saying “with his knife”. Several of Lassen’s comrades spoke of his love of this weapon, and of the way in which he put himself “in a trance, so that he saw no danger in anything” during the fighting in Symi, and how “once he got going he’d kill anyone”.

[15]

It cannot be ruled out that Lassen used his knife on Symi, but eyewitness accounts concentrate on the ferocity of the firefights.

Several of Lassen’s comrades, who were not particularly squeamish otherwise, found his eagerness to “slaughter bastards” somewhat alien. Some attributed it to a particularly bloodthirsty nature, others likened his hatred of the Germans to that of the Greek resistance. Both he and the Greeks fought against an enemy that had occupied their homeland. The eyewitnesses on Symi – like other places where he saw combat – agreed that Lassen showed extraordinary bravery and cold-bloodedness, even by SBS standards.

*

Around noon, First Lt. Fresemann was informed by radio that he could not count on air support as the Stukas were busy elsewhere. Shortly after, he found out that his men at the bridgehead on Muglia were running out of ammunition. At the same time, Esperia was being fired on by a 20-mm gun mounted on a British caique off the mouth of Pedi Bay. The Germans returned fire with a 28-mm anti-tank gun. After a 10-minute firefight, the British vessel pulled back, but the Germans were now under fire from both ends of the bay. At 13:00, Fresemann gave the order to withdraw. The last man was on board Esperia by 13:30, and Fresemann immediately gave orders for departure. During the embarkation, the motorboat Parma and the confiscated rowing boats that ferried the Germans from the beach out to Esperia came under fire from a 20-mm cannon in the town. No one was hit, but the shelling made it abundantly clear that the time had come to leave Symi. Just as the last Germans climbed aboard Esperia, three Stukas flew over the coast and bombed the town. At 16:30, Fresemann received instructions by radio to resume the attack, with a promise that reinforcements were en route from Rhodes. Before he had time to so much as think about obeying the order, the sailor responsible for Esperia informed him that there was only one vessel in the harbour at Rhodes ready to sail, and it could take a maximum of ten men. Fresemann continued to Rhodes, arriving at 19:00.

It perhaps says something about the severity of the fighting that both sides dramatically overestimated the enemy’s strength. In his report, Fresemann estimated an enemy force of about 100 British (all “big and powerful figures”) and 200–300 Italians. According to a British report, the Germans landed 120 men.

[16]

While the German estimate of the number of Italians was fairly acurate, the number of Britons (even including the 45 RAF and SAAF men) was unlikely to have been 100, and the German landing force, as mentioned previously, consisted of only 54 men. When the reports about the abortive landing on Symi reached Marinegruppenkommando Süd, the number of British troops on the island had risen to 300 men “in bunkers”. The very next day, the Germans started to plan a new raid on Symi, with a larger force from Division Rhodos.

[17]

British losses amounted to one dead (hit by several shots to the head and chest, according to Dr Ferris) and a handful of wounded. Five Italians were wounded. Among the British wounded were Lt Charles Bimrose, who was hit in the right upper arm, but insisted on fighting on. When he later underwent surgery at a hospital in Cairo, two 9-mm bullets were found side by side in his arm. Seven Greeks were killed and several wounded. German losses amounted to two dead and four badly wounded (one of whom later died in the field hospital), plus one slightly wounded and nine missing. Six of the missing Germans had been taken prisoner, while the other three were probably killed – either during the fighting or perhaps later by Greek civilians when they tried to hide in the mountains.

[18]

If the information that Lassen killed at least three Germans is to be believed, he alone was responsible for over half of the German casualties.

*

According to the Italian head teacher in Symi, the locals were impressed that the Germans managed to get away from the island under the noses of the British and the Italians: “What devils, the Germans!” Nevertheless, the raid on Symi was a rather costly defeat, and the Germans did not attempt to land again right away. Instead, the island became the target of a series of massive air strikes. On 8 October, Stukas attacked the town five times. Four British troops were killed when Lapraik’s command post was hit. The Italian carabinieri barracks were destroyed, the port commander was injured, many homes were destroyed, and Dr Ferris’s infirmary was razed to the ground, killing two nurses and six civilian patients. In total, more than 40 Greek civilians were killed during the first attack. The air raids continued for three days and destroyed most of the town. The bombing was so violent that Lapraik and his Italian colleagues assumed that it was the prelude to a new German landing, and had their men take up defensive positions. However, around 22:00, Lapraik received orders to evacuate Symi immediately. At 23:00, the British sailed for Kastellorizo, and at midnight the Italians followed with all of the garrison’s weapons, food, etc. Before leaving, the British set fire to the Italian ammunition and fuel depots, resulting in a fire that destroyed all of the homes in the town’s Murajo district. Lapraik’s men also burnt some caiques that were being repaired, while 17 seaworthy vessels, along with their crews and their families, were taken to Kastellorizo. Many young Greeks left the island with the British to sign up for the Free Greek forces in Cyprus.

[19]

The Germans did not notice that their enemies had left the island, so the air strikes continued until 22 October.

[20]

In the weeks after the evacuation, the SBS returned to Symi several times. On the night of 18 October, a caique sailed into the town’s harbour, and the two British officers on board met with the Italian harbour commander for two hours. Over the following week, the British paid two more night-time visits to deliver food to the locals. The food was of Italian origin, and the final shipment, which came from Leros, consisted entirely of canned goods. The locals concluded that the British were clearing out stocks ahead of an evacuation of Leros.

Around the same time that the two British officers were visiting the port commander, Lassen and his patrol went ashore at Panormitis, on the opposite side of the island. Here, they blew up the Italian radio station and took eight Italians prisoner.

On 24 October, a German reconnaissance mission to Symi was postponed due to engine trouble. It was not until 2 November, after a spy had informed the Germans that the British and Italians had evacuated, that a new German force arrived on the island. It was set ashore from a motorised vessel accompanied by two patrol boats, two motor boats and fighter planes. According to the Marinegruppenkommando Süd war diary, the force only met “resistance from light anti-aircraft guns, which were silenced by Junker Ju 88s”. Unfortunately, the diary does not say anything about who was manning this battery two weeks after the British evacuation. This time, the Germans installed a small garrison consisting of two officers and 50 Italians who remained loyal to the Axis. Its primary task was to staff and protect a telephone exchange that secured the connection to Rhodes via an underwater cable, and a radio station that connected Symi town with Panormitis.

[21]

[…]

. On the night of 6–7 April, two SBS patrols, each consisting of nine men and an officer, sailed to the north shore and attempted to land. They came across a dike and a deep channel that ran parallel to the shore, behind which was another dike. The moon was about to come out, and the raiders could hear German patrols on the coast road. They abandoned the plan to go ashore but blew holes in the dam with plastic explosives to let the enemy know they had been there.

On the night of April 7–8, Lassen sent three folboats to Comacchio to reconnoitre the coast between Comacchio and Porto Garibaldi, where he planned to go ashore with a force the following night. In one of the boats was Greece expert Sergeant Les Stephenson, who still felt rather out of place in these strange surroundings, and Trooper Freddie Crouch, a former policeman from London who had recently been plagued by nocturnal out-of-body experiences – which he interpreted as an omen of his own death. The three patrols were rowing into a fierce headwind and made very slow progress. It was shortly before dawn when they finally approached their goal. This meant that they had to return without achieving their objectives in order to avoid being caught in the middle of the lake when the sun came up, which would have given away the fact that the raiders were interested in this particular part of the coast.

Lassen was concerned about the lack of reconnaissance, but 2nd Commando Brigade maintained that the operation should go ahead.

[22]

On 8 April, the men on Agosta and Caldirolo again had to spend a whole day hiding in mud holes. But that night they were to carry out the biggest attack of Operation Fry. Lassen divided his men into four groups and sent them into action at various locations along the northern shores – some to fight and draw attention to themselves, others to reconnoitre without being detected. The Royal Engineers detachment was sent up to the dike that demarcated the lake to the west, to investigate whether patrols could be sent ashore east of Argenta. A small patrol from M Squadron landed at the salt works in the north-east corner of the lake, where they conducted a thorough reconnaissance and questioned local people – a sure-fire way of ensuring that the Germans would get wind of British interest in this area.

One of Lassen’s two combat groups, under the command of Captain Stud Stellin, made another attempt to climb the high dike and cross the deep channel along the northern shores west of Comacchio, but had to retreat when they were spotted by German sentries.

Lassen himself led the last of the four groups – 17 men divided into two patrols – which would disembark on the shores of Comacchio and Porto Garibaldi and from there head north-west along the coast to Comacchio. Their job was to kill as many Germans as possible, take prisoners for interrogation and cause maximum confusion. This would presumably give the Germans the impression that a much larger force had landed, in advance of a major attack on this part of the front. Lassen led E Patrol, which consisted of ten men besides himself. Lieutenant Turnbull, a newcomer to the SBS, had six men under him in Y Patrol.

[23]

*

The sun went down over Lake Comacchio at 20:00, and the attacking force sailed from Caldirolo shortly after. The waning moon had not risen yet. Some of the raiders sailed in folboats, others in larger craft. Lassen, Stephenson and Sergeant Waite sailed with Ettore Tomasi and Mario Foschini Cavalieri in their batana. From Caldirolo, they sailed toward Valle Fattibello, crossed the Cona and Fosecchie dams, sailed on through the Pallotta Canal and into the dam along the shore by the village of Raibosola, just south of Comacchio.

[24]

*

As they lay off the dam, Lassen produced a bottle, took a swig, and passed it to Tomasi and Cavalieri. The drink was strong and Tomasi had not tasted it before. Lassen asked where they should go ashore. Tomasi pointed out the German positions and left the rest up to Lassen.

As Lassen led his men ashore, they first had to cross a canal that ran parallel to the shore, before moving up to the road between Comacchio and Porto Garibaldi. The road, which was around 15 feet wide, ran parallel to the railway track on a low dam, with the canal to the west and a flooded area of six-feet-deep mud to the east. Lassen sent two scouts up the road, followed by the rest of E Patrol, with Y Patrol about 100 yards further back. He himself was in the rear of E Patrol from where he could maintain contact with Y as well

After about 500 yards, the raiders were challenged by a guard shouting from a dug-in machine-gun post.

[25]

*

Lassen did not entirely trust the two fishermen, so he had left them at the boats. The force’s only Italian-speaking member, Private Freddie Green, was sent up to join the scouts. He told the guards that he and his comrades were fishermen from Sant’Alberto on their way to Comacchio. Out of sight, the raiders had taken up positions in the darkness behind Green, ready to intervene if something went wrong. Green had no experience in bluffing, especially not enemy machine-gunners. Nonetheless, he succeeded in delivering his message and repeating it three or four times. At first, the Turkmen sentry seemed to be convinced by Green’s Italian. But just as the raiders were about to advance on the position and silently despatch the men occupying it, two machine guns in the post opened fire.

[26]

*

The opening salvo wounded the two scouts and Freddie Crouch, and alerted the two machine-gun positions further up the road. The three posts had been positioned so that the ones at the back could fire over the top of those in the front. The raiders returned fire, but in the darkness and confusion, some of the men had advanced too far and risked being hit by friendly fire. It was a hugely difficult situation – but Lassen acted decisively to save his men. Lassen had been just behind Green when he tried to fool the sentries. When the machine guns opened fire, he had thrown himself to the ground. Now, he ran toward the machine-gun position and threw two hand grenades in quick succession before storming it, followed by his men. Lassen was known for his ability to throw far and accurately, and the grenades did their job. Four stunned Turkmenian soldiers were killed, either by the grenades or by bullets.

The two machine-gun positions further up the road then opened fire, as did a fourth position slightly to the left of the road, about 300 yards further away. Five or six machine guns were now firing down a road that was just 15 feet wide. Lassen braved the hail of bullets to run towards the next position, to the left of the road. This allowed his men who had taken up positions on either side of the first machine-gun nest to shoot freely without risking hitting him. From here, Lassen threw three hand grenades towards the second German position. This shocked the crew so much that they ceased fire momentarily. Lassen seized the opportunity to lead another assault. He fired a green flare and stormed forward, alternately blowing his whistle and yelling at his men: “Come on! Forward, you bastards!” This position, too, was manned by four soldiers with two machine guns. Two of the defenders were killed in the attack, while the other two were taken prisoner and sent back for interrogation.

[27]

In the meantime, the third machine-gun position in the row, as well as the fourth, further back in the dark, had sent up flares. They now concentrated their fire on the position that the raiders had just stormed. The heavy fire killed Fusilier Stanley Raymond Hughes and Corporal Edward Roberts. Sergeant Waite was hit in the leg and was unable to move, but continued shooting from a prone position. Sean O’Reilly was also wounded, his shoulder shattered by a machine-gun bullet. The total force was now down to ten men armed with handguns, a Bren gun and hand grenades.

Disarray and confusion reigned among the raiders. Trying to get away from the road and the railway line, they took cover in the water and mud on both sides of the dam. Lassen gathered his men and ordered them to concentrate their fire on the third and nearest machine-gun position. He had already used all of his grenades, but took more from Stephenson – who in return received a lecture because he had not pulled out the pin.

The thing is you don’t pull that till the last minute, you don’t run around with a loose pin. But that went over my head, I knew that was Lassen, it didn’t bother me, those remarks, one would expect that, it was almost a compliment.

[28]

From inside the machine-gun position they now heard the cry “Kamerad”, the standard call meaning that the crew wanted to surrender. Lassen stood up, but ordered his men to remain under cover. He stepped onto the road and ran toward the machine-gun position. He stopped around three yards away and shouted in German to the defenders that they should come out. At that, a machine gun opened fire from the left side of the post.

[29]

*

Maybe it was a trick by the defenders, or maybe they were unsettled to see Lassen running toward them holding weapons while unseen enemies were still firing on them. Lassen’s men could barely see the machine-gun position. They had seen Lassen run up to it and then fall or throw himself to the ground and disappear from sight. They did not know if he had been hit or sought cover. When the shots were fired, Lassen threw a hand grenade into the post and wounded some of the defenders. One of the machine guns continued to fire, but the raiders responded in kind – and it fell silent.

After “a few seconds but it seemed like twenty minutes” the raiders heard Lassen shouting: “SBS! Major Lassen wounded!” Stephenson was the first to react. “I heard him shout again so I then went across to the pill box, you’ve got to make your mind up.” Stephenson found Lassen lying on his back, apparently unconscious, to the right of the entrance to the post. He had been hit by gunfire in the side of the abdomen or groin. Stephenson put his arm under Lassen and supported him against his knee, trying to lift him up. Lassen started to talk. He said that he was dying and that Stephenson should leave him, because trying to evacuate him would just put the other raiders’ lives at risk. Stephenson was to tell Lieutenant Turnbull to take command and continue the attack.

[30]

*

Stephenson reached into his back pocket and fished out the morphine tablets that raiders always carried with them on operations. He placed one on Lassen’s tongue. He again tried to lift the wounded man up to carry him back to the others. But Stephenson was not a big man, and had difficulty lifting the wounded Lassen, who weighed around 12½ stone. His backpack then got tangled in a phone line that had been downed by one of the explosions. He tried again to carry or drag Lassen away and yelled at his comrades. At last, another raider joined them. Stephenson wanted him to help carry Lassen, but the man said: “Oh, he’s dead, there’s no point.” Leaving Lassen behind, Stephenson and his companion headed back through the darkness and the shooting to find Turnbull.

[31]

According to the report that Turnbull wrote a month after the event, he shouted “Andy, Andy!” and heard the reply “Carry on, carry on!”

Regardless of which order Turnbull received from Lassen, and when and how he received it, he decided to abort the operation. By now, the raiders had almost exhausted their ammunition – and without Lassen to spur them on, it was pointless trying to continue. Turnbull fired a red flare as a signal to retreat. As well as Lassen, who was either dead or dying, the force left behind two dead and five missing, of whom at least two were wounded. Some of the boats had been hit by gunfire and were useless. Tomasi and Foschini used mud to patch holes in their batana, and took eight men on board instead of the three on the outward journey. O’Reilly, his shoulder smashed and bleeding heavily, tried to soothe the pain with cigarettes.

[32]

When the raiders sailed out onto the lake, they left one of their boats on the shore in the hope that the missing men would find it and escape.

It was around 03:00 when Tomasi and Cavalieri punted their boat out on the lake. To get out of range of the German weaponry as fast as possible, they steered first south-west and then west. This was not the course set by the British. “[They] were angry with me because I did not follow the routes that they had stipulated. But afterwards they understood it.”

When the remains of the force made it back to Caldirolo, O’Reilly’s wound was treated, but it proved impossible to remove the bullet with the limited medical resources on the island. The next morning, he was sailed down to the south coast and taken by jeep to Ravenna, from where he was flown to a hospital. The other wounded were transported to San Alberto, just south of the lake, and treated there.

[33]

Of the five missing raiders, Alfred John Crouch was killed, but the two unharmed men managed to help their wounded comrades on board the abandoned boat and row to a nearby island, where they remained hidden until they were extracted safely the following night.

[34]

*

At dawn on 9 April, the Germans and Turkmen brought their dead to Comacchio but left their enemies where they had fallen. The people of Comacchio did not dare venture out of town after the gunfire during the night. Nor did they dare show sympathy for the German’s enemies, so the corpses were left there until the town priest, Don Francesco Mariani, did something about it. He had repeatedly risked his life to help escaped Allied prisoners of war with shelter and money. Now, with the aid of some of the townswomen, he collected the bodies of Lassen, Hughes and Roberts. (Crouch was not found until later and was buried where he fell.) The bodies were brought into Comacchio, after which Don Mariani and the women prepared them for burial and laid them to rest in the town’s old cemetery. It had been demolished during Napoleon’s reign, but was brought back into use after the flooding perpetrated by the Germans had made the newer cemetery inaccessible.

[35]

*

The news of M Squadron’s losses reached the other SBS units during 10-12 April.

[36]

Private Ken Smith, who knew Lassen from the Aegean, responded with a shrug when he heard that “Lassen’s ’ad it” and that Roberts, Hughes and Crouch had also lost their lives. Neither Smith, nor the other raiders who responded similarly, were particularly unfeeling. It was just that:

after five years of war, human life was just not as precious as it is in peacetime. We had lost a lot of friends, and we all knew that we could be killed at any time. So, when we heard that Lassen and the others had died, we shrugged our shoulders, said “Oh well” and drank another mug of coffee.

[37]

Those closer to Lassen responded more strongly, of course. Freddie Green, who himself had almost been killed during the battle on the Spit, “cried incessantly for two days”. Others reacted with sorrow, shock and disbelief.

David Sutherland was in the Yugoslav mountains when he received word.

I went as white as a sheet, we all did, we simply couldn’t believe it. We thought that this man was totally indestructible. He’d been through so much and this was the last thing that he’d get killed doing. We were very upset about that and morale went down, absolutely rock-bottom.

[38]

"Word is 'Vendetta'" - The abduction of General Kreipe

Anders Lassen-thessaloniki, October-November 1944

Anders Lassen - From Operation Postmaster to Comacchio

A short talk obout Anders Lassen on Crete - Operation Albumen - SENFORCE

[1]

Hancock: Interview with Mike Langley.[2]

Langley 1988/2016, p.161.[3]

Cavallari 1943.[4]

On Guardia di Finanza: Cecini, Giovanni (2014): La Guardia di Finanza nelle isole italiane dell'Egeo 1912 – 1945. Gangemi. Rome[5]

WO 201/1663.[6]

Le operazioni delle unità italiane nel settembre-ottobre 1943, chapt. IV.[7]

rhodesianafricanrifles.co.uk/alan-gardiner-redfern-mbe-%C2%B7-november-11-1943/ and unithistories.com/officers/Army_officers_R01.html (both acc. 16 December 2018); Lassen 1949/1965, p.85; HS 5/716; Report on Erratic Operation conducted from Cyprus; Base between 22 Sept 1943–8 Oct,; Long Range Desert Group, Operation Report No. 99, in Private Papers of Major General D.L. Lloyd Owen CB DSO OBE MC at the IWM. According to Suzanne Lassen’s account, ‘After a few days had elapsed, Anders contacted the Abbot and managed without the knowledge of the Italians, to get a radio operator installed on the mountain behind the monastery… The Greek who was to operate the set was introduced to the monks as the Abbot’s nephew.’ (Lassen 1949/1965, p.85). Suzanne Lassen does not mention the source of her information. It seems unlikely that both the SBS and the LRDG (which by now was specialised in this form of work) would have an observation post in the same place, or, if in fact they did, or if Lassen had helped the LRDG.[8]

Cavallari 1943; Lodwick 1947/1990, p.83.[9]

Ferris: Account.[10]

Betr.: Unternehmen “Trianda”, Sturmdivision Rhodos, 6.10.43 (RH 26-1007/6); operation reports RH 26-1007/10).[11]

Cavallari 1943.[12]

The various German accounts (RH 26-1007/10) do not fully concur on this point, nor on the geography, but taken together, they suggest that the Germans felt that the antenna was on or in the immediate vicinity of the citadel where Lassen had positioned his patrol and his 20-mm cannon.[13]

Cavallari 1943.[14]

Langley 1988/2016, pp. 160-161.[15]

Hancock: Interview with Mike Langley; Langley 1988/2016, p.177. Here, Langley also quotes Porter Jarrell and Dick Holmes, who again cite an unnamed eyewitness.[16]

Lassen 1949/1965, p.90.[17]

RM 35-III/63[18]

The German casualty figures are taken from Fresemann’s Gefechtsbericht über das Landungsunternehmen Simi, 1 November 1943 (RH 26-2007/10). These figures are significantly lower than those in Lodwick and Suzanne Lassen and Lapraik’s account, cited in Le operazioni delle unità italiane nel settembre-ottobre 1943, Ch. III, from which the Italian casualty figures are taken.[19]

Le operazioni delle unità italiane nel settembre-ottobre 1943, chapt. III; Cavalari 1943.[20]

Gefechtsbericht über das Unternehmen gegen die Insel Simi vom 1. bis 3.11.1943 (RH 26-1007/7).[21]

Gefechtsbericht über das Unternehmen gegen die Insel Simi vom 1. bis 3.11.1943 (RH 26-1007/7); Abendmeldung 2.-3. november 1943 (RM 35-III/65).[22]

Lassen 1949.[23]

As well as Lassen, E Patrol consisted of Company Sergeant Major Workman, Sergeant O’Reilly, Bombardier Crotty, Trooper Crouch and privates Shaw, Thompson, Barbour, Medcalfe, Green and Stephenson. Y Patrol consisted of First Lieutenant Turnbull, Sergeant Waite, corporals Roberts and Watkins, Fusilier Hughes and privates Williams and Hunter. The men had not volunteered for the operation, but had been handpicked by Lassen.[24]

The countryside around Comacchio has changed much since 1945. The land that the Germans had flooded was drained again after the war. Since then, several other new areas have also been drained. Part of the route that Lassen’s force sailed would today cross the dry land north of the lake.[25]

In British sources, these machine-gun positions are often referred to as “pill boxes”, which suggests a small concrete structure above the ground. In fact, they were foxholes, which were presumably covered with turf-lined boards. The German infantry’s foxholes for light machine guns were generally intended for a single weapon operated by a gunner and an assistant. However, the positions on the Spit were apparently wider, with room for two machine guns operated by a total of four men (Langley 1988/2016, p. 234; in general on German field fortifications: Rottmann 2004).[26]

According to Tomasi, he asked Lassen, as they parted on the lakeshore, if he knew the password. Lassen said that he did, but that very night the Germans had changed the password, and so the sentries opened fire on Green and his comrades. None of the British witnesses mention any password.[27]

The prisoners belonged to 6th Company, 2nd Battalion, 303rd Infantry Regiment, 162 (Turk.) Infantry Division (2 Cdo Bde Report on Op ”FRY”, WO 218/76). About the green flare: Sergeant Waite, quoted in Lassen 1949, p.226.[28]

Stephenson: Interview with Mike Langley.[29]

According to 2 Cdo Bde Report on Op “FRY” (WO 218/76) of 17 April 1945, the men in the machine-gun post came out with their hands up. Another position to the north-west then opened fire. This description of events is inconsistent with that of Stephenson, Lieutenant Turnbull, Company Sergeant Major Workman and Bombardier Crotty. It is difficult to imagine who might have been able to see the Turkmen leave their position. The brigade report also fails to mention one of the German machine-gun posts. According to this report, the raiders defeated the first post without losses, but then Lassen was killed in front of the second in the row – and not, as in the other reports, the third.[30]

Shortly after the war, Stephenson sent Suzanne Lassen a written account of the night’s events. He told her that Lassen had said that he should give Turnbull the order to withdraw (Stephenson: Interview with Mike Langley). However, according to Turnbull’s own report of 8 May 1945, Lassen had given the order to press home the attack. In principle, the two versions are not mutually exclusive. Lassen may well have given the order to continue the attack, but impressed on Turnbull that he should get his men out safely.[31]

Stephenson: Interview with Mike Langley.[32]

Tomasi: Interview with M. Paiola.[33]

Tomasi interview with M. Paiola.[34]

2 Cdo Bde Report on Op “FRY” (WO 218/76).[35]

Nazareno Bellini: Interview with author, Comacchio, 9 April 2002. Don Francesco Mariani helped 1,034 Italian and Allied soldiers cross the Gustav Line into Allied territory during the war. For this effort, and for providing pastoral care and practical assistance to the victims of the Allied air attacks in 1945, Comacchio council honoured him with a gold medal in 1955.[36]

Milner-Barry TS, p. 341-342.[37]

Kenneth Herbert Smith: Interview with author, Comacchio, 9 April 2002.[38]

Sutherland, 1999, p.143. Interview with Mike Langley.