The Tribunal finds that knowledge of these criminal activities was sufficiently general to justify declaring that the SS [including the Waffen-SS] was a criminal organisation […] It does appear that an attempt was made to keep secret some phases of its activities, but its criminal programmes were so widespread, and involved slaughter on such a gigantic scale, that its criminal activities must have been widely known.. […]

(International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 30 September 1946)[1]

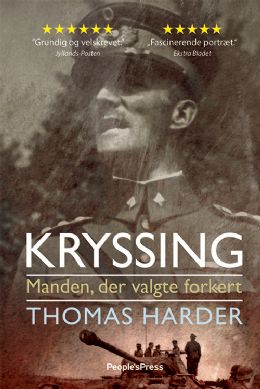

During the almost two years I have spent trying not only to chart C.P. Kryssing’s life, but also to understand his thoughts and feelings, people have often asked me whether I have ended up liking the man and whether I have come to find it wrong that he was punished. To the first question I must say that I find it hard, and to the second that Kryssing’s punishment was right and necessary, even though, for several reasons it was unjust, and the politicians and authorities involved in his case could and should have shown themselves more humane.

I have no doubt that Kryssing was an honest and decent man with a strong sense of responsibility and that he took good care of the men under his command and was loyal to his friends. I’m also certain that he was genuinely devoted to his wife and wished of all his heart to be a good husband to her. He probably loved his mother and his sister Ingrid and his two sons. He had a certain sense of humour and self-irony and was able to look at himself and his faults with an honest and detached eye. He was also a man of physical and moral courage, and a man who cared about his dignity and stood by his word. Good qualities, all of them. On the other hand, he was also naïve and proud and stubborn to an almost pathological degree, which in conjunction with a marked lack of political and moral judgment made him a dangerous man – dangerous to himself as well as to those around him – and drove him to make himself an accessory and accomplice to crimes of monstrous proportions.

Denmark’s judicial reckoning with those who had collaborated with the Germans was not pretty, neither from a legal point of view nor from a moral one. Retroactive legislation has no place anywhere, and it is hard to see the justice in punishing Kryssing and the other volunteers, while the politicians who had given them permission to join Frikorps Danmark went free and were mostly able to continue their careers after the war.

On the other hand, it is also hard to see any alternative to the retroactive laws and to the sentencing and punishment. It served to avoid mob justice and sent a clear signal to the Danish population and to the Allied powers that Denmark distanced itself from the occupation period’s active cooperation with Nazi Germany – as far as this was possible without also distancing itself from the political parties and persons who had been responsible for this policy. The punishment inflicted on Kryssing and the other volunteers was unjust, but from a pragmatic and political point of view it was necessary. And it was right to punish a man like Kryssing who had incurred a particular responsibility.

Kryssing did not break any Danish law when he joined Frikorps Danmark, and he even had the express permission of the Danish Government to do so. Nevertheless, he should have known better. Not in the sense, as it was suggested after the war, that he ought to have considered the Government’s permission invalid because it was granted under pressure and was in conflict with the opinion of the majority of the Danish population – citizens must assume that their Government will always stand by any permissions it grants. But Kryssing’s conscience should have told him that it would always be wrong, under any circumstances, with or without the Government’s permission, to fight alongside Nazi Germany. Kryssing was not a 17-year-old boy who knew nothing about the world and allowed himself to be dragged along by his much-admired father. He was a mature man who should have said to himself that no matter one’s opinion of the Soviet Union and Communism, it could never justify cooperating with Germany. Not only because Germany had occupied Denmark, but because Germany was ruled by a criminal regime based on a perverted and murderous ideology. Kryssing, however, was far from the only national conservative Danish officer to whom this thought apparently did not occur. It is striking that Kryssing’s officer colleagues who wrote him asking him not to go into German service did so because, in their view, a Danish officer could not serve the occupying power. They did not write that a German officer could not serve Hitler.

Nothing seems to indicate that during his service with Frikorps Danmark or the Waffen-SS Kryssing committed war crimes or crimes against humanity. He did not serve in concentration camps, he probably did not order the murder of Jews, Communist commissars or other prisoners of war or civilians, and he probably did not witness such crimes himself.

That does not mean that he did not know about them. Even before accepting command of Frikorps Danmark he knew how the Nazis linked communism and Jewishness, and like all other newspaper readers he knew how Jews were treated in Germany. After hearing Jüttner’s[2] speech upon the Frikorps’ arrival at Langenhorn, Kryssing cannot have been ignorant of the fact that Germany's war against Russia was not only a war against a competing great power and a political system, but also very much a war of annihilation. In Owinska he stayed in a house maintained by Jewish prisoners, and he must have heard how the former psychiatric hospital was cleared of its patients to make room for Frikorps Danmark. We don’t know what the future Standartenführer Poul Ranzow Engelhardt and his comrades did or did not tell about their experiences with the 1st SS Brigade, when they joined the Frikorps, but even giving Kryssing the benefit of the doubt and assuming that they kept the stories of the atrocities at Owinska to themselves Kryssing ought to have asked himself – at Langenhorn, if not before – what business a decent man like himself had among such criminals.

The Copenhagen District Court considered it an aggravating circumstance that Kryssing had chosen to stay with the Waffen-SS after being sacked from the Frikorps. One has to agree with the Court’s decision.

Apart from still wanting to fight ‟the butcher of Finland”, Kryssing also had his own very human reasons for staying on in the Waffen-SS: He did not want to leave his two young sons behind alone after they had volunteered because of him, nor did he want to return to Denmark as a failure. Both reasons are very understandable, but by remaining in the Waffen-SS Kryssing contributed to maintaining a system which made mass-murderers of hundreds of thousands of men who otherwise would not have become criminals. In that respect it is neither here nor there that, as the decent and well-meaning ‟K.K.” wrote to their comrades from the Danish Military Academy, Kryssing was an idealist convinced that he acted in the service of a good cause. Kryssing was on the wrong side, and even though his actions were not illegal according to Danish legislation, and even though he had his government’s approval, he incurred a moral co-responsibility for the atrocities of the Third Reich.

It would obviously have been impossible to allow Kryssing and the other officers who had volunteered for German service to stay on in the Danish military. It would have been a source of constant conflicts and disciplinary problems, and it would have sent some highly undesirable signals about the democratic mindset of the Danish armed forces and undermined the Danish Government’s efforts to secure a place for Denmark in the allied camp. It followed from the Danish Civil Service Act that officers who had been dismissed on such grounds should lose any pension rights earned through their service in the Danish armed forces – a service which in Kryssing’s case had lasted 28 years. It would have been becoming for the Danish authorities if they had found some discreet way to, if not actually pay out the lost pensions, at least offer men like Kryssing some sort of employment that would allow them to earn a living and perhaps contribute to their resocialisation – given the fact that the wartime government had explicitly approved their joining the Frikorps.

*

Kryssing’s CO in the Danish Army, Colonel C.D.O. Lunn, wrote about him that mentally he was on a tram ride: Once he had started his journey he was unable to leave the track. One might also say that Kryssing was politically and morally blind. He lacked the moral and political judgment, which prevented so many other Danish officers, who otherwise agreed with Kryssing about so many things, from serving the Germans and even made many of them join the Resistance movement. As an officer of the Waffen-SS Kryssing was a colleague and comrade of people who championed rabid Nazi and racist views, and he cannot have been ignorant of the German armed forces’ mass killings of prisoners of war, Jews, presumed Communists, and other civilians, just as the concentration camps cannot have been a secret to him. He was, however, able to ignore these crimes or to consider them insignificant compared to the higher purpose which he had gone to war to fight for. Kryssing was by no means alone in suffering from this political and moral blindness during the war, just as the disclosure of the full extent of the crimes of Nazism – which in no way made him regret his choice – has not protected later generations from allowing themselves to be struck by the same kind of blindness in other contexts.

Copenhagen, 21 August 2014

Thomas Harder

[1] International Military Tribunal, The Accused Organizations, Judgement: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judorg.asp The International Military Tribunal recommended that all SS-officers with the rank of sturmbannführer or higher be sentenced to ten years of prison, and lower-ranking officers to five years, simply for their membership of the SS. However, this recommendation was rarely followed

[2] Obergruppenführer Hans Jüttner, chief of staff of SS-Führungshauptamt (SS Leadership Main Office).