(This text was translated by Tam McTurk from an early version of the manuscript. It does not correspond 100% to the published book, but does give a fair impression of En sten for Eva.)

Foreword

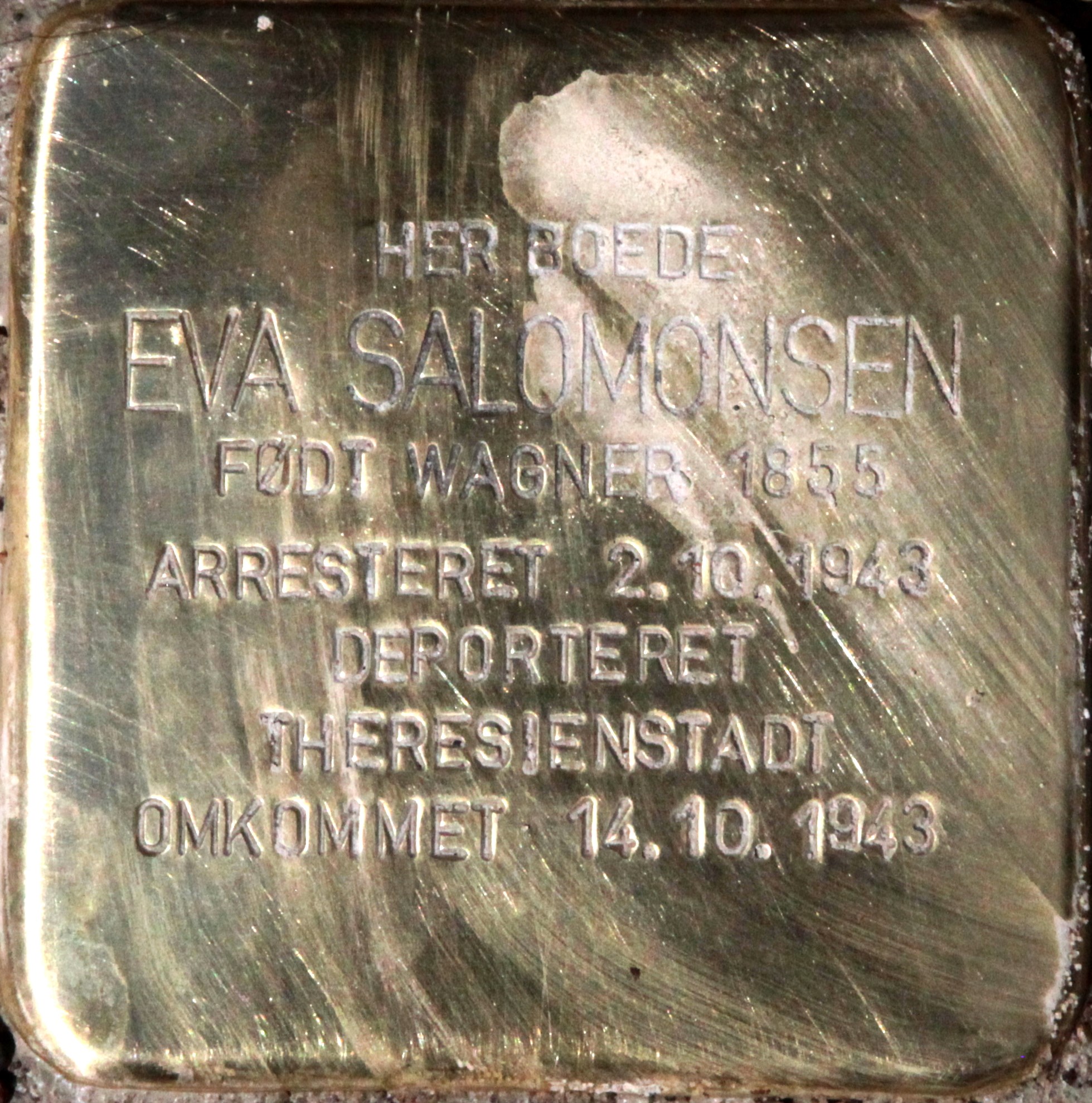

The “stumbling stone” outside Bredgade 51 marks a crime scene. On the night of 1–2 October 1943, a crime was committed here – against an ailing 88-year-old, and against humanity.

We do not know the names of the individuals who dragged Eva Salomonsen from her home to begin the journey to Theresienstadt, where she died shortly afterwards. But we do know a great deal about the system of which they were a part. We are only too aware of its ideology and aims, which included the eradication of whole swathes of the population who were considered undesirable.

The intention was not simply to murder individuals – albeit in their millions – but literally to wipe whole groups from the face of the Earth, to erase all memory of them, as if they had never existed.

The idea behind this book, like the stumbling stone project (Stolperstein in German), which names the victims and connects them to specific places, is to prevent memories of the Holocaust from fading into oblivion. It does so by telling the story of Eva Salomonsen’s life, her world and her final days.

Although it is about a single victim of the Nazis, the book also seeks to remind us of the many

The book also tells the story of how Eva Salomonsen’s son, David, and his two daughters escaped to Sweden during the war. It recounts their lives as refugees, the two young women’s work in the Danish Brigade, their return to Denmark, what they found when they came home and what they brought with them.

At one point in Otto Gelsted’s novel Jøderne i Husaby [“The Jews in Husaby”] – a fictionalised account of fleeing to Sweden during the German occupation and life as a refugee – Sonja, a Jewish woman, says to the author’s alter ego, Tingsted:

“I’ll tell you one thing, though: if you write about us, it’s bound to be wrong.”

“That’s highly likely. But what makes you say so?”

“You weren’t brought up in a Jewish household. You haven’t lived among us. Your prejudices, your tastes, will keep getting in the way. You’ll judge us from the outside. No matter how sympathetic you are, it won’t help. You’ll still get it wrong.”

“Yes, well, I’ve given that some thought and decided it’s a risk I’ll just have to take. It’s impossible to write anything that nobody could misunderstand and distort with a little goodwill.”[1]

Neither of us comes from a Jewish background. Like Tingsted, our view of the Jewish world is from the outside. We have gone to great lengths to learn about Jewish culture and history to help us relate the story of Eva Salomonsen and her world as faithfully and comprehensively as possible. We have read a great deal, searched for information in all sorts of sources, and sought advice from many knowledgeable and helpful individuals. If we have misunderstood anything or written anything that is wrong or flawed, the fault lies with us alone and not with the many kind souls who have helped us in our work.

We have made an honest attempt to learn as much as we can about Eva and her loved ones, and to portray their surroundings and the world in which they lived as accurately as possible. However, there is still much we do not know about her. If you are able to add to our picture of Eva, we would very much like to hear from you.

Lene Ewald Hesel & Thomas Harder

Bredgade 51, June 2022

Introduction

It did not take long before the initial idea of a stumbling stone for Eva Salomonsen led to us thinking about a book about her life. At first, the information we unearthed suggested that we might end up with a rather narrow depiction of her life and fate, and a brief glimpse of her son and his daughter’s flight to Sweden. We established contact with the researcher Silvia Goldbaum Tarabini Fracapane, genealogists, the Jewish Community in Denmark and the local museum in Eva’s hometown of Bogense. This provided a solid foundation for our work, along with Danish Holocaust survivors’ published recollections, our own notes from conversations with survivors and other witnesses, as well as, of course, the extensive literature on the history of the Jewish people in Denmark, the occupation, Theresienstadt, etc.

We placed ads in the Jewish Community’s printed and digital newsletters in an attempt to locate relatives of Eva or people who could add something to her story, but to no avail. In May 2020, thanks to Søren Dalsgaard and the genealogical website MyHeritage.com, we made contact with Eva’s great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren, people with personal memories of David Salomonsen and his daughters, and who still live in a family marked, for better or for worse, by Eva’s fate. In addition to the relatives’ own memories and observations – direct personal experience and oral family history – we gained access to photographs, letters, diaries and a variety of other materials. These significantly broadened the book’s horizons and made it possible to learn much more about Eva’s son and grandchildren. In particular, Annelise’s diaries and memoirs from 1943–45 tell the remarkable story of her and David’s escape from Denmark, and depict everyday life as a refugee in neutral Sweden.

The genealogical trail also allowed us to trace Eva’s lineage through time and across Europe. October 1943 was not the first time her family had faced persecution in Denmark. Her father was three years old in 1819 when his father’s shop in Odense was plundered during the anti-Jewish Hep Hep riots.

[...]

Eva’s Childhood home – Bogense in the mid-19th century

Odense has been called ‘The Sun in the planetary system of Funen towns’ because it is the biggest and located approximately in the centre of the island, surrounded by all the others, which appear to be rather regularly spaced along the arc of the coastline. Kjærteminde thus becomes Mercury, the name of the planet closest to the Sun, and since Bogense is a fraction closer to Odense than Nyborg

Søren Harries Clausen, under the pseudonym Literis Mando, Bogense Byes og Skovby Herreds Topographi og Historie fra Sagntiden til Nutiden [The Topography and History of the town of Bogense and Skovby Herred from the Mythical Era to the Present, 1859]

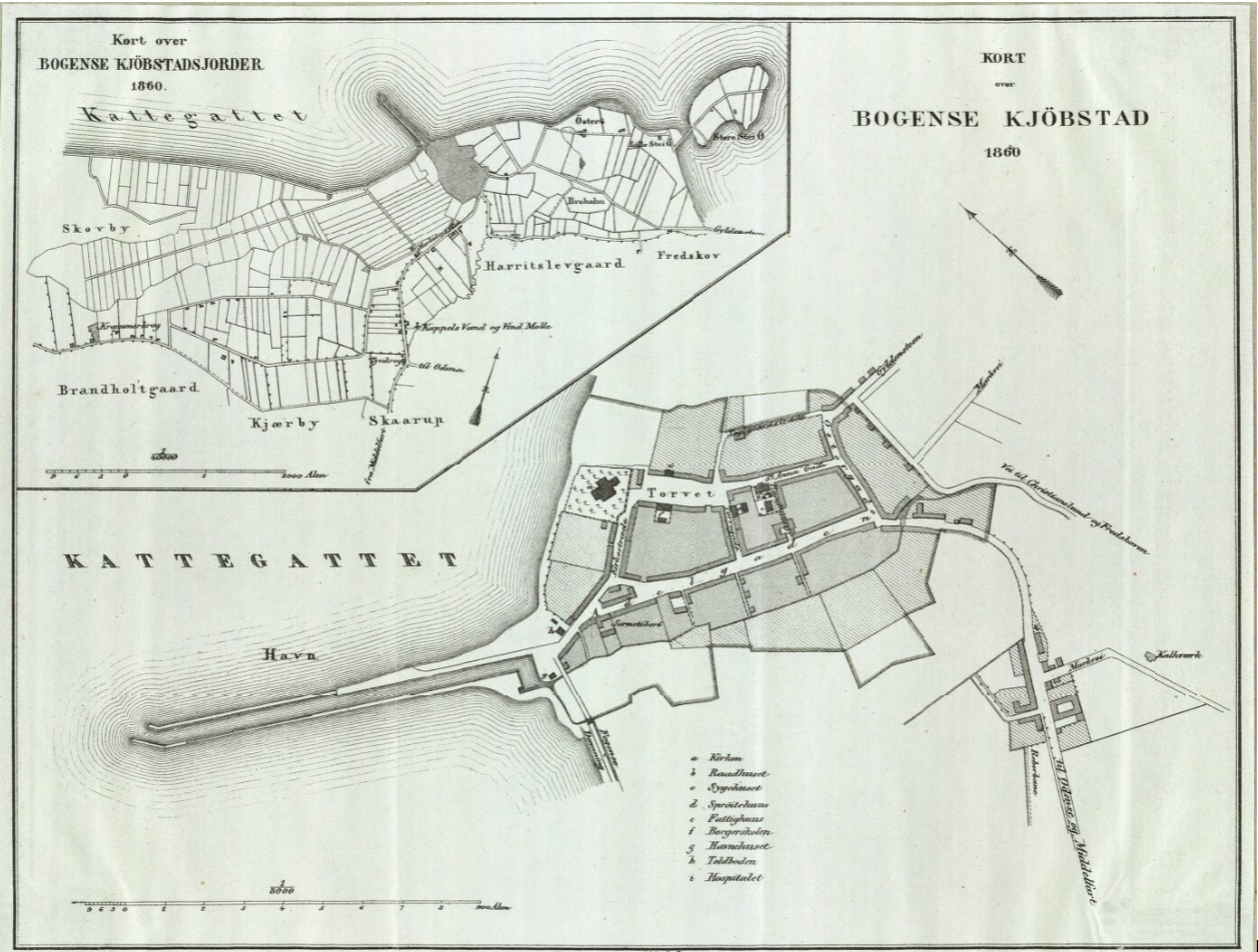

Ill.: Map of the borough of Bogense, 1860

The smallest market town on Funen in 1860.

The heart of Bogense in the mid-19th century was the square

Primarily, however, the square was a place where people gathered for smaller markets and trading. (Larger markets and cattle shows were held on a bigger site out of town. As might be expected when town and country came together to make merry, these were lively affairs – with stalls purveying fancy knick-knacks and tents in which strange and disturbing phenomena were on public display.)

Thursday was market day on the square, with stalls selling vegetables, poultry and delicacies (including rich foods such as pork, hams, sausages, butter and tallow). It was also the site of various other markets, such as a girls’ market (known as “the Cabbage Market”) in autumn, a summer market in early July, a Michaelmas market (29 September) and a big herb market in autumn.

From the square, St. Annagade passes the old town hall, which had its own jail, and leads to Østergade, formerly “Tjæregade”, a commercial hub lined with shops and workshops. This street was the site of the old general store – originally several smaller buildings that were amalgamated into one big one in the 18th century Here, you could purchase almost anything your heart desired:

The shop contained a coffee machine, tubs of margarine, barrels of rice, salt, grains and peas, glass cabinets with tobacco and wine; from the ceiling hung kitchenware, on the wall whips, ropes, cow tethers and bits. Under the long counter were drawers with sugar and flour, a space for soap – not to mention jars of sweets – while bags of weighed goods, spices, preserves and the like were kept on the back counter. In the back store were barrels of schnaps, spirits and vinegar. The floor was scoured white and strewn with sand.[2]

It was very much a mixed bag – and it had to be because the customers came not only from the town, but from miles around. Farmers could not just nip into town whenever they felt like it, so when they did, they bought in bulk. A trip to town was a day out, and once they had done their shopping, they would repair to the taproom and partake of their packed lunches. Big grocery stores like this remained popular until the advent of smaller, local shops and village cooperatives in the villages.

Bogense also had butchers, bakers, blacksmiths, saddlers, tailors, doctors, barbers, coopers, brass-finishers, hatters, brush-makers, clog-makers, soap-makers, distillers, tanners, ropemakers and maltsters – not to mention vendors selling shells and sand. Crushed seashells were an important dietary supplement, primarily for the chickens many of the townspeople kept in their backyard. Sand was sprinkled on the floors, either before brushing them to keep the sweepings together, or afterwards, as decoration, for which fine, light-coloured sand from the beach was popular. “The first thing a new apprentice had to learn was the knack of strewing sand evenly across the floor.” In the latter half of the 19th century, people stopped using floor sand and began to treat their floors with varnish or veneer.[3]

Further down Østergade were the hardware store S. Quist, the pipe-maker J. Rasmussen and coppersmith Arthur Storch, whose name still adorns the gable to this day. Across the road, David I. Wagner’s draper’s shop occupied one of the smaller buildings – formerly the one-storey abode of a postmaster and revenue inspector.

Ill.: Photo from Gamle Bogense Billeder [Old Bogense Pictures]

Wagner’s draper’s shop was in the small one-storey building on the left, between the painter Willemsen (with the awning) and the baker Pedersen (with the pretzel sign) (1880).

In the 1830s, the streets of Bogense were finally paved – not with flat setts but with rounded cobblestones, which made a terrible noise when farmers rode into town on heavy carts. In 1873, the local newspaper Bogense Avis opined that “the paving of the streets here in the town, as everybody knows, is in such a state that no other market town in Denmark has any claim to worse”. Only later were setts laid, and the “[open] gutters that served to keep the streets clean” replaced by proper sewers.

Originally, the public water supply in Bogense came from the stream that runs through the town. Maids fetched water from the channels that connected the stream to Adelgade. The quality of the water was questionable to say the least, and in 1847 a number of health and safety measures were introduced: under no circumstances were “sweepings, dead dogs, cats or other carrion to be thrown into the stream”; the many local dyers and tanners were only allowed to rinse their goods at certain spots; and “privvies”, pigsties and dunghills had to be at least 10 alen (about 20 feet) from the stream. It was usually the nightman’s job to empty the “privvies” or latrines. If he was unable to access the privy from a backyard, he would carry the buckets out through the house.[4]

Ill.: Bogense, the stream ...

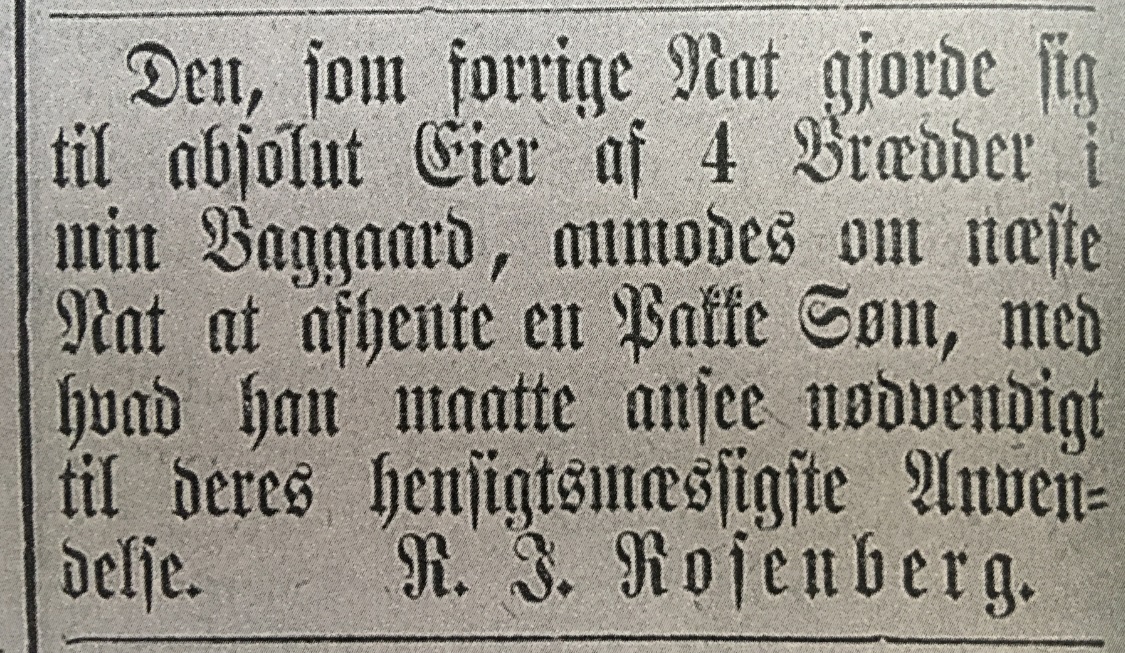

Bogense Avis was first printed in 1859, on a late-18th-century hand-operated press. Although it brought news from Denmark and abroad – the many theatres of war and royal courts in particular were accorded plenty of column inches – the main emphasis was on local stories. For example, on 29 January 1861, R.I. Rosenberg placed the following notice in the small ads section:

Ill.: Rosenberg’s ad, Bogense Avis, 29 January 1861

Whomsoever made himself the absolute owner of four planks of wood from my backyard last night is requested to pick up a bag of nails tonight, along with whatever else he may deem necessary for their appropriate use.

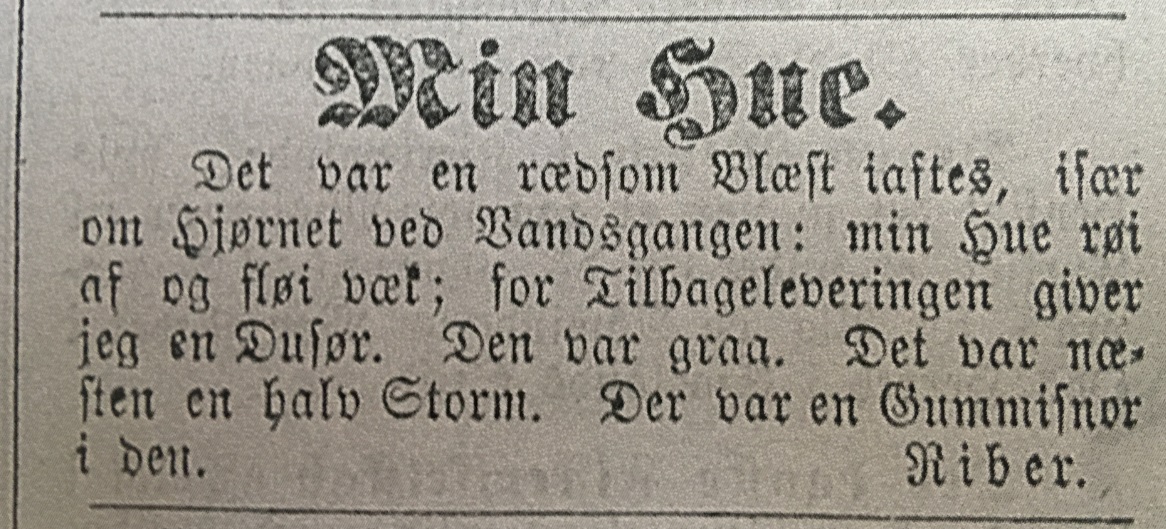

On 4 February 1868, iron founder and head of the town constabulary B.C. Riber placed this notice in the paper:

Ill.: Bogense Avis, 4 February 1868

My cap. A terrible wind was blowing last night, especially on the corner at Vandsgangen: my cap blew off and away; for its return I offer a reward. It was grey. It was blowing half a storm. It has a rubber strap. Riber

In 1855, the population of Bogense was 1,709. On 15 July, that number increased by one with the arrival of Evaline Wagner. The draper David I. Wagner and his wife Amalie now had four children: Julius (8), Emilie (6), Bertha (4) and newborn Evaline.[5]*

Amalie (née Bernhard) hailed from Malchin – a small market town in the northern German Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The town had a Jewish community from the mid-14th century until a wave of pogroms in 1492. A new one was established in the mid-18th century, partly as a result of immigration from the east. A synagogue opened in 1764, followed by a Jewish graveyard in the early 19th century. However, Jewish people remained second-class citizens, reliant on “letters of protection” issued by the authorities, which granted them certain limited rights to live and trade in the town. They were also subject to a number of restrictions and taxes. At its height in 1824, the Jewish community in Malchin numbered 124.

Amalie moved with David to Bogense, where he had a “licence to trade” as a grocer. At first, he sold delicacies such as cigars and wines and “Steam chocolate from the ‘Elisabethsminde’ factory in Copenhagen”.

Ill.: Advert

Steam chocolate was cooking chocolate “produced by steam power”.

Later, however, perhaps due to growing competition from the grocer’s store, David concentrated on manufactured goods such as calico, carpets and “arthritis felt” (“This relief from arthritis manufactured by Mr. C.F. Machold in Copenhagen is recommended by esteemed physicians”).

The household also included a young man – a shop assistant – who helped David while learning his trade. In 1855, the position was held by 19-year-old Nathan Marcus Heckscher, who came from Copenhagen and later returned to his native city, where he became a wholesaler. In 1860, the position was held by Amalie’s 17-year-old nephew Sigismund Bernhard, from Malchin. Some years later, the apprentice was, by all accounts, a boy named Benny from Copenhagen.

In the mid-19th century, traffic was lively across both parish and national borders. In 1850, Amalie’s unmarried older sister Friederike (known as Rieka) moved in with the family to lend a hand. She is unlikely to have spoken Danish, so

The household also had, of course, at least one maid to take care of the domestic chores. And there was more than enough to do. Aside from endless hours of toil cooking on the wood-fired stove, doing laundry in the copper boiler, and looking after the tiled stoves for heating, paraffin lamps, spittoons, chamber pots, etc., every household had to fetch water every single day of the year. In the 19th century, there were six pumps in Bogense. One, as mentioned, was in the square, another was at the Adelgade/Østergade junction, and a third was on St. Annagade. The standpipes also served as notice boards, and maids would meet here and enjoy a brief respite while swapping news and gossip.

The monthly “big wash” used colossal amounts of water, so on these days the children were probably sent to the pumps, too. The wash was heavy, hard work that took days and required lots of soda crystals, yellow soap and elbow grease. As a rule, a seasoned washerwoman directed the course of the battle, which generally proceeded as follows: On day one, dirty cotton and flax garments were soaked in large vessels with water and soda crystals. On day two, the clothes were boiled in the copper boiler with soda and yellow soap. On day three, the washboard came into play. Once the clothes had been thoroughly scrubbed with soap, they were rinsed several times – the last time with bluing, to counteract the yellowish hue that many textiles assume with age (despite the name, bluing makes the garments look whiter). After that, the clothes were hand-wrung and hung out to dry – nice ones in plain view, more intimate garments such as underwear and menstrual “aprons” more discreetly (inside pillowcases, for example). Eventually, the clothes were taken in and sorted, ready for the mangling board, the roller or an iron, which was either heated on the stove or filled with charcoal and/or embers.

During the winter months, ice had to be collected to keep food cool. A handful of men equipped with special long saws headed to the frozen lakes and streams to carve out blocks of ice. These were then carefully wrapped in insulating straw or raw peat and stored in cellars or pits to make them last as long as possible – preferably all the way into the summer.

In 1856, the first streetlamp in Bogense was installed on the busy corner of Adelgade and Østergade. Later, more were installed around the town, and it became the watchman’s job to fill them and to turn them on and off. At first, they used expensive whale oil, then paraffin, which proved just as costly. In 1862, residents complained that the watchman was squandering fuel. He was instructed not to “turn on the lamps on moonlit nights”.

Those who were out and about in the dead of night might encounter the watchman. Equipped with a lantern, bell and mace, he maintained law and order and marked the hour by singing a watchman’s song. At 10 pm, he would sing:

Do you want the time to know,

Girl, boy or sire?

Then, it’s off to bed you should go,

Succumb to that desire.

Our Lord commands all men!

Be smart and bright!

Careful with fire and light!

The clock has now struck ten.

Fire had ravaged Bogense several times, so when he called on people to take care with fire and light, the watchman was being quite literal. In the event of a fire, a drummer would parade the streets warning townspeople and gathering men to fill leather buckets from the stream that wound through the town.

The town policeman also used the drum as he walked around making public announcements. He was even willing, for an appropriate fee, to convey messages of a more private nature. After an initial drum roll, he would proclaim “It is hereby announced...”, followed by all manner of information, about everything from court hearings and auctions to “Smoked herring now available!”[6]

When Evaline and her siblings were not at school or helping out in the shop or home, they would make the most of the surrounding area’s rich opportunities for play. Girls and boys probably indulged in different pursuits, but it is unlikely that the girls’ upbringing was unusually strict – Evaline’s older sister Emilie, for example, was constantly running in and out of the neighbours’ houses (see later). Behind several of the shops were large timber yards, where children could play hide and seek. In winter, they ice-skated. In summer, they could spend hours on the beach, swimming and fishing for sticklebacks. Sometimes, they would place improvised miniature boats made of bark into the stream at Skovvejen, and then run along the watchman’s path, follow their boats all the way to the harbour and watch them sail off across the sea. However, the beach was not without its perils – the area was infested with mosquitoes. A single bite could infect the victim with malaria, which required treatment with quinine powder. The disease was not eradicated in Denmark until the late 19th century.

Other forms of entertainment included markets and cattle shows, travelling theatres and menageries. In 1855, the Jewish circus family Goldkette visited Bogense, presenting their “Art Performance”, “the content of which will be announced on posters”. On Sunday 18 March 1866, assuming that their parents had given them permission, Evaline and her siblings may have seen this magnificent specimen of a camel and other exotic animals on display in widow Thomsen’s coach yard.

“Also on show are a Russian bear and a mandrill exercising with a sabre and a rifle. All of the circus’s animals do tricks.”

Evaline’s father joined

In 1863, the guild posed for a photograph in the square complete with flags and top hats. In the middle of the square is the standpipe; in the foreground (far right), the town constable.

Every year, the town council published a list of local taxpayers (whose contributions were measured in “stones” – a system unique to Bogense). [7]* These lists suggest that David Israel Wagner was rather wealthy. In addition, public bankruptcy announcements suggest that he was highly regarded – enough to be chosen as an executor. During 1854–60, David also served as a member of the town council.

All the indications are that Wagner’s draper’s shop was popular and reputable, and that the family was well integrated.

And yet, perhaps life was not as idyllic as it seemed.

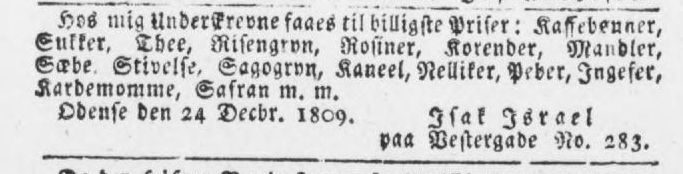

David had not always lived in Bogense and not always been called Wagner. As a child, he lived in Odense, where his father, Isaac Israel, who had immigrated from Germany, had a combined clothing and grocery store, where he sold delicacies such as coffee beans, tea, currants, cloves, ginger, cardamom and saffron.

Ill.: Fyens Stifts Kongelig allene privilegerede Adresse-Avis og Avertissements-Tidende (Newspaper on Funen) 1809:

If on Christmas Eve 1809 you needed the last few items for the big festive meal, you could always send an errand boy to Evaline’s grandfather in Vestergade.

In the same newspaper on the same day: “A red-embroidered christening gown is being sold by Isaac Israel,

Ill.: Christening gown

Advert for christening gown. Note that the street number is different from the previous notice.

One important observer of the Wagner family’s life in Bogense is professor and chief surgeon Peter Kisby Møller (1847–1940), who as a child lived with his grandparents in Bogense, where the grandfather was a district court judge. His memoir

From this time I have retained several other memories: of the neighbour, the Jewish draper Wagner, whose little daughter Emilie regularly came in and played with me. She was very lively and amused Grandfather a lot, including at her naïve outburst:

“There was still […] in the early 1850s” may refer to the aftermath of the

Ill.: “Letter of freedom” 1814

Frederik VI’s Decree of 29 March 1814, laying down the Rules to be Observed by Adherents of the Mosaic Religion who reside in the Kingdom of Denmark, is often called “the Jewish Letter of Freedom”. However, it did not grant new rights to Jewish residents – they were still subject to a number of restrictions. In fact, it obliged them to comply fully with the laws of the country, denied them the right to invoke specific religious laws or rabbinical regulations on any civil matter, and imposed upon them a number of new obligations. The decree also granted the state influence over the leadership of Jewish congregations and required rabbis to be appointed by the king. The Jewish community was not granted full equality with other faith communities until the Constitution of 1849.[10]

The young Hans Christian Andersen, who had just moved from Odense to the capital, later

The night before my arrival, the rioting had broken out, the whole city was on the move, it was almost impossible to make your way along Østergade; the expectations I had of the mass of humanity thus struck home. The troubles disheartened me quite severely, I felt so alone, and in a strange city.[11]

A few days later, the rioting spread to several provincial towns, including Odense. Isaac Israel, Evaline’s grandfather, was among those worst affected: his shop was razed and looted, and he heard an angry mob outside his home, intent upon burning it to the ground. Fortunately, the troublemakers gave up and moved on to the next victim, but only after causing quite extensive damage:

Around 8pm, a large throng gathered in Overgade, where several Jewish families lived. However, probably warned by the mood in the city, they had closed their shops early.

The crowd clapped their hands and shouted, “Jews out – hep, hep, hep”. The chief constable turned up twice and called on the crowd to disperse in a calm and orderly manner, but he was drowned out. Having failed, the chief constable removed himself from the scene, leaving two officers behind. However, they were only able to observe subsequent events powerlessly.

Immediately afterwards, stones were thrown at David Israel’s house. The windows were smashed, but the crowd did not force their way inside.

At the same time, stones rained down on Isaac Israel’s property and shop in the same street. On the ground floor, the shutters initially offered protection against the stoning, but in the living quarters on the first floor, all 45 windows were smashed. The mob attacked the shutters and doors on the ground floor with sticks and stones and broke them open. Several people forced their way in. The shop was badly damaged, the inventory smashed up, drawers broken into and all of the wares either destroyed or strewn about the street, where rioters quickly helped themselves. The proprietor stayed in a room behind the shop while all of this was happening but could do nothing to stop it on his own. At one point, Isaac Israel heard one of the intruders say that they should burn the building down. To prevent this, he rushed into the kitchen and put out his fire. Immediately afterwards, the merchant – hiding under the kitchen table – saw three men enter the kitchen, where they were disappointed to find that there was no fire on the hearth. The looting lasted about an hour, during which time the merchant stayed with his family on the second floor, as far from the shop as possible. They suffered no physical harm.[12]*

Ill.: Fyens Stifts Kongelig allene privilegerede Adresse-Avis og Avertissements-Tidende from 14 September

Odense. Contrary to all our hopes, here too, wanton individuals of the simplest class dared to defy law and order on Sunday evening by attacking the houses of inhabitants of the Mosaic faith. The police and the Diocese Commander made amicable representations to those breaching the peace to refrain from their actions, but in vain. First, the windows and doors of a merchant on Overgade were broken. After the shop had been looted and many of his wares strewn across the street, the riotous mob made its way to Korsgaden, where another shop was attacked, the windows smashed with stones and the ironwork on the stairs broken. Finally, the violence was stopped, and the crowd dispersed by a horseback patrol from the army and local militia, which continued to patrol last night, thus preventing further outbreaks. The Constabulary had warned everybody in advance to keep their boys off the street and keep their gates and doors closed after 8pm. Several participants in these disgraceful events, mainly young men, were apprehended and can now expect public punishment for their deeds, as a deterrent to like-minded individuals. Due to the effects of the measures taken and the intense loathing that every righteous citizen feels for such abominations, one can surely hope that the peace will not be breached again, and that the sanctity of the home, which under the protection of the laws should be sacrosanct for all, will not be violated again.

Nothing speaks more strongly of the degree of baseness and depth of ingratitude to their benefactors to which people can sink, than that one of the apprehended rioters’ parents has for several years received considerable weekly sustenance from the family whose place of residence he was particularly active in attacking. Nor was there any lack of examples of the opposite way of thinking, however. Thus, one house against which the mob rallied was saved by the swift and steadfast actions of

Ill.: The last pages of the inventory of Isaac Israel’s losses[13]

“The list of goods that were abducted with violence from me on 12 September 1819.” The list spanned six densely written pages.

The shocking events of 1819 led several members of the Jewish community – both in the capital and in the provinces – to convert to Christianity. This did not stop them from following Jewish precepts or marrying into other Jewish families, but it made them feel less vulnerable. Others changed their names or moved house. Isaac Israel did neither, but the experience seems to have broken his spirit. Even though it seems that he received some compensation for the stolen and damaged goods, his hitherto thriving business wasted away, and his marriage to Elle broke down. The couple divorced, and Isaac ended up in the poorhouse, where he died in 1840, aged 90. Elle died in 1848, aged 71.[14]

David Israel did not convert, but as an adult he assumed the less conspicuous surname Wagner and moved to Bogense in 1839.

As the town’s leading draper, it was important for David to show off his wares. His wife and daughters undoubtedly wore garments of the finest fabrics and highest quality. During his many business trips to suppliers and factories, he amassed “a very wide selection of the newest and most tasteful fabrics that the fashion of today has to offer, and in terms of fashion I now have a larger stock than ever before”.

Many feet of fabric went into a single dress, not to mention the numerous petticoats, with or without stays of various kinds. The dome-shaped crinoline, which consisted of horizontal steel rings suspended from wires, had its third heyday in the mid-1850s, when it replaced the heavy horsehair petticoat that had previously been used to give dresses their voluminous shape. The crinoline was lighter than the horsehair petticoat and allowed greater freedom of movement. However, the crinoline was only for adults and older girls – the younger girls still wore petticoats, as well as visible pantalettes that could be decorated with lace edges.

Note the different dress lengths in the photograph below. Amalie’s dress goes all the way down to the ground, while Emilie’s is slightly shorter so you can see her footwear. Both are probably wearing a crinoline under their dress. Bertha and Evaline’s dresses are only slightly below the knee, so their pantalettes are visible.

Ill.: Photo of Amalie and her three daughters

Amalie and her three daughters, probably photographed in the mid-1860s. From left: Bertha, Evaline, Amalie and Emilie. Evaline is holding her mother’s hand, but all of the daughters look somewhat ill at ease. The makeshift outdoor stage suggests that the picture was taken by a travelling

The Jewish community in Bogense was very small. Aside from the Wagner family, there were the brothers Meyer and Hirsch Levinsohn – a butcher and merchant, respectively – and a few others. But although most were well integrated, some stuck out in the small community, such as the pauper Ruben: “a skinny old Jew who sometimes forayed the town and surrounding area to beg for food, which he placed in a barrel that he wore on his back. He would dress in black, with a top hat and wooden clogs, and wander off mumbling and pointing with his stick at the houses he intended to visit. He lived in the poorhouse.”[15] Even Levinsohn, the butcher, apparently caused a stir:

There were a number of notable characters in Bogense: I remember old Meyer, for example, who was Jewish. I once met him down in the hotel yard, where he was shuffling along in a pair of giant pants. He was a distinctly Jewish type, and I clearly remember meeting this old man and his unusual look.[16]

It is difficult to say anything about the nature of the Wagner family’s Judaism at this time. Evaline’s older brother Julius is not registered as circumcised,[17] but that may have been an error. We do know that he later married a Jewish woman and his own sons were circumcised. However, we do not know whether the family ate kosher food in Bogense. Levinsohn, the butcher, may in theory have sold kosher meat, but there would only have been a limited market for it in the town. On the other hand, it would have been relatively easy for the family to avoid eating pork. They may have eaten a slow-cooked stew (cholent) on the Sabbath: “because Jewish people, as we know, may not light a fire on Saturdays, and so brought their food to the boil on Friday afternoon before sunset and placed it in a sealed dish in a kind of oven.” This “oven” was an insulated box filled with ash and glowing

Ill.: Recipe

The same year that Evaline was born, Juliane Dahl’s Praktisk Kogebog for enhver Huusholdning [Practical Cookbook for Every Household] was published. It contains several recipes rooted in Danish-Jewish cuisine, such as “Jewish Easter Eggs”: butter-fried, sugar-strewn cakes

The difficulty involved in eating kosher food was not the only obstacle to Jewish life in Bogense. Not only was there no synagogue, there was not even a private prayer room, because a minyan (the congregation that must be present for important prayers) requires 10 adult men – fewer than lived in the entire town. Nor was there a Jewish graveyard – the nearest ones were in Odense, Assens and Fåborg. Virtually all provincial Jewish communities faced similar challenges, and the vast majority of them were dissolved in the late 19th century.

Whether it was due to business reasons, a desire for greater contact with the Jewish community or better marriage prospects for the children, the Wagner family moved to Copenhagen in 1867. Thanks to a series of closing down sale ads, followed by advertisements for auctions of the remaining inventory, and a few notices announcing that the family house in Østergade was first for rent and then for sale, we have been able to follow their preparations for the move.

Ill.: Advertisement, Bogense Avis 1867

We also gain an insight into how the small home in Østergade was furnished, with “Mahogany, birch and beechwood furniture such as sofas, chairs, tables, wardrobes, pedestals, writing desks, 1 buffet, mirrors, linen and bed clothes, 2 lamps, kitchenware of all kinds, stoves, 1 mangle, 1 clock and all other domestic utensils such as glass, faience, 1 dinner set, copper and woodenware, etc.”

In P.K. Møller’s words, Bogense was:

isolated from the outside world and external influences and left to its own little area, with its limited – both in number and scale – interests, partially stagnating. As far as shipping is concerned, a few schooners sailed corn to England and brought back coal, small cutters sailed with general cargo to towns in Jutland, and perhaps once in a while to Copenhagen, or had fairly regular routes to the small island of Endelave. Once a week, a steamship sailing between Copenhagen and Fredericia would stop in the roads, picking up or dropping off a small amount of goods and, occasionally, a passenger. The main link with the outside world was the daily stagecoach between Bogense and Odense, which left Bogense at 7pm, Odense at 6am.[19] [...] As a rule, the small town was quiet and idyllic. Under the bailiff and local minister, the townspeople felt safe. It was also comforting to know that your life and health were in good hands with the two doctors, District Doctor Larsen and Dr. Nees.[20]

What did this seclusion mean to a girl like Evaline? Was she fond of living in a small town where everyone knew each other, and uncomfortable with the prospect of moving somewhere bigger, which would place new and greater demands on her? Or was she tired of small town life where everyone knew each other and longing for something bigger, somewhere she could live more freely?

Did she feel as if she stood out? Had she or her family sensed an underlying or even thinly veiled anti-Semitism? Did she feel lonely?

Unfortunately, we do not know her thoughts, hopes and dreams from that time, as there are no oral nor written accounts from her years in Bogense.

The bark boat of her childhood now set its course for Copenhagen.

[...]

Deportation

On 8 September 1943, Reich Commissioner for Denmark Werner Best sent a telegram to Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop saying that the state of emergency should be used to resolve the “Jewish question”. The recommendation, which conflicted with his previous policy, was accompanied by multiple provisos and warnings. It is likely that Best thought Hitler would soon issue orders to strike at the Danish Jews, and that it would be in his interests to be seen to take the initiative

On 17 September, the German Foreign Ministry replied to Best, stating that the deportation of the Danish Jews had been approved in principle, and requested that he submit tangible plans. The following day, Best responded that there were 1,673 Jewish families in Greater Copenhagen and 33 in the rest of the country, plus 1,208 people who had emigrated from Germany and 110 families who no longer belonged to the Jewish community. To facilitate transport from Greater Copenhagen and the rest of Zealand, Best asked for “a ship capable of accommodating at least 5,000 people”. Trains were to be used for deportation from Funen and Jutland..[22]

The number of Jews in Denmark was estimated on the basis of information from a range of sources, including a card index prepared for the German Embassy by the anti-Semitic genealogist Lorenz Christensen. This index, consisting of over 2,000 cards, was completed in August 1942 and handed over to the Gestapo. It was supplemented with material from two raids: on 31 August 1943, three armed Gestapo officers, including the Dane Paul Hennig, entered the office of Supreme Court lawyer C.B. Henriques in Nybrogade and seized older records concerning the Mosaic Community. On 17 September 1943, the Gestapo raided the Jewish community office on Ny Kongensgade, confiscating ledgers for 1942–43, a 1935 voter roll and an overview of Jewish immigrants to Denmark since 1933.*[23]

Following the dissolution of the Danish government, rumours were circulating that action was imminent, and many Jewish people no longer slept in their homes. A small number had already fled. The two Gestapo raids heightened the sense of unease, as did the fact that members of a German police battalion who transferred from Norway to Copenhagen on 26–30 September were overheard speaking openly about coming to Denmark to deport the Jews.*[24]

Ill.: Paul Hennig

One of the three Gestapo men who seized records on 31 August was the Dane Paul Hennig. He was a former writer for the anti-Semitic publication Kamptegnet, an independent genealogist who produced Arierregisteret [The Register of Aryans] and a Waffen-SS volunteer. Based on Christensen’s file and the material from the Mosaic Community, Hennig drew up arrest lists that included people with no connection to the Jewish community, possibly because they were married to non-Jews or had even been baptised.

On 28 September, the German Foreign Ministry asked Best when the deportations would begin. Best replied that he intended to take action on the night of October 1–2, provided that the necessary shipping capacity was available. On the same day, the German Navy’s High Command ordered the ships Monte Rosa and Lappland, which regularly sailed between Oslo and Aarhus and Aalborg, and Wartheland, which served as a target ship at the German Navy’s torpedo schools in Mürwik and Travemünde, to be ready for embarkation from Copenhagen on 1 October at 20:00. Monte Rosa was to take 2,000 Jews on board, and the other two ships 1,500 each. On the same day, a freight train was ordered to transport the deportees from Swinemünde to Theresienstadt. On 29 September, German and Danish railway officials met in Fredericia and approved the transport from Aalborg.[25]

Ill.: German Naval High Command document

Naval Warfare Command’s order of 28 September 1943. The word “people” is crossed out and replaced with “Jews”. “No meals are to be provided on board. Guards, 50–60 men per ship, provided by the SS. No additional accommodation to be provided on board” (RM 7/2162, BAMA).

It is doubtful whether Best ever imagined that shipping capacity for 5,000 people would actually be needed. During September, G.F. Duckwitz, Maritime Attaché at the German Embassy, warned his Danish and Swedish contacts what lay ahead. He probably did so following discussion with Best, who wanted to limit the impact of the action so as not to damage relations with the Danish authorities any more than necessary. Although Best wanted to “cleanse” Germany and the German-controlled areas of Jews, it made little difference to him whether this was achieved through murder, forced emigration or flight. Nor is it inconceivable that Best had foreseen that the war could end in a German defeat, in which case it would benefit him to be perceived as the saviour of the Danish Jews.[26]

On September 28, Duckwitz informed senior Social Democrats, with whom he was on good terms, that the deportations were imminent. Duckwitz also made sure that the Swedish Embassy in Copenhagen and the Foreign Ministry in Stockholm were informed.

That same night, the warning was conveyed to C.B. Henriques. On 29 September, Rabbi Moritz Melchior passed it on to the congregation at the morning service in the synagogue in Krystalgade. (It is not known precisely how many people were in attendance – perhaps up to 100.) The warning was also widely shared via other channels. It is likely that the vast majority of Jews in the Copenhagen area were warned of or at least heard rumours about the impending raids.[27]

The Bishop of Copenhagen, Hans Fuglsang-Damgaard.

On the morning of 29 September, C.B. Henriques informed the Bishop of Copenhagen, Hans Fuglsang-Damgaard, about the latest developments. That same day, the bishop delivered a letter of protest to Nils Svenningsen, the Permanent Undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and to the Permanent Undersecretary at the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs, Th. Thomsen, asking that it be relayed to the German authorities. After the government resigned on 29 August 1943, Svenningsen was the leading figure in the group of senior civil servants who formed the de facto administration – albeit in close unofficial contact with the former cabinet. The bishop also issued the text as a pastoral letter to every clergyman in the country and suggested that they read it aloud at services on Sunday 3 October. In the letter, Fuglsang-Damgaard stated that it was the Christian church’s duty to protest everywhere that “Jews are persecuted on racial or religious grounds”. He said that this duty arose from the close kinship between Christianity and Judaism: “Persecution of the Jews runs counter to the concept of humanity and charity that stems from the message that the Church of Jesus Christ exists to preach.” He went on to say that “it goes against the Danish people’s sense of justice, which has for centuries been enshrined in Danish-Christian culture.” On 30 September, the largest employers’ and agricultural associations and trade unions approached Best, noting that action against the Jews would greatly damage joint efforts to maintain law and order, let alone efforts to ensure productivity and profits. Their statement concluded: “The Jewish people are part of Denmark, and steps against them will be felt by the entire nation.” The following day, 1 October, the Danish Women’s Council, which represented 100,000 women through its 58 affiliated associations, also wrote to Best to express:

… the hope that Danish citizens will not be persecuted because of their faith and race. Such persecution is completely alien to Danish thinking and our sense of justice, and we are convinced that it will awaken a feeling of such inescapable national debasement that a deep and enduring bitterness will ensue.

Similar protests were voiced by others, and Christian X stressed in a letter to von Ribbentrop, which he asked Svenningsen to hand over to Best, “that special measures for a group of people who for more than 100 years have enjoyed full civil rights in Denmark could have the most serious consequences”.[28]

As rumours swirled and warnings circulated via word of mouth in Jewish circles, the permanent secretaries tried in vain to get Best to confirm or deny that action was imminent. At Bredgade 51, Dr. Drucker and his family probably heard about the impending deportations as early as 29 September. At the time, Eva was very ill, feverish and confused – her neighbour Dr. Gram described her as “almost dying”. Even if the Druckers did try to warn her before they went into hiding, she probably would not have understood. Perhaps the 23–24-year-old maid who lived with her (and who was to be replaced on 1 October by a live-in nurse) received the message but did not know what to do about it – or it might be that, like Eva’s family, she could not imagine that the Germans would bother about a sick old woman.[29]*

Word of the impending raids reached the Salomonsen family on the morning of Thursday, 30 September. When Annelise showed up for work at the insurance company Nye Danske af 1864 in Stormgade, her boss, actuary Paul Johansen, told her to notify her father immediately that they were in danger, and not to sleep at home.*[30]

Shortly after 10am, Annelise arrived at Forhaabningsholms Allé 11. She woke up David and, with some difficulty, convinced him that the situation really was serious. She told him to transfer his own and Eva’s money somewhere safe as soon as possible, and then go to Annelise and Mogens’ apartment in Herninggade to spend the night there. She called Mogens, who rushed over to help David gather important papers and pack essential items. Annelise then went back to the office while Mogens and David went to the bank. During a three-hour meeting with the branch manager, they transferred Eva and David’s money and the contents of their safe-deposit box to an account and box under an acquaintance’s name. That evening, all three met at the flat in Herninggade. David spent the night in Annelise’s bed while she slept on the couch.

The next morning, Friday 1 October, Annelise and Mogens left early, while David slept in until the afternoon. Annelise went to the office, as “rumours of impending raids on Jewish homes spread like wildfire and everyone was doing what they could to flee the country”. Throughout the day, she called people who might be able to help. At one point, she visited a potential lead, who was unable to make promises on the spot but said they would contact her as soon as an opportunity to flee presented itself.

For Annelise, these increasingly hectic preparations took place against a background of mundane, everyday tasks – which seems almost absurd in retrospect and in the light of subsequent events.

After office hours I was to meet with Miss Nielsen [David’s housekeeper who lived in the flat on Forhaabningsholms Allé]. We were to shop on the way, and then she would help cook and sort cucumbers that I had bought for pickling. On the stairs, we met Dad and Mogens. Mogens had been to all sorts of places in search of a way out and had eventually obtained papers from the visa office for use in applying for an exit permit. We completed the papers in the evening, providing information on everything under the sun,

Annelise, Mogens and David spent the evening discussing what to do. Should they leave, or stay and wait for events to unfold?

We eventually agreed to leave if it could be done completely normally as ordinary passengers. The next morning Mogens was to go to the visa office with the papers and our birth certificates, as only Mogens had a valid passport. Likewise, we agreed that the next morning I would find Tove and tell her what we were going to do and ask whether she wanted to come. Then we went to bed like the night before.[31]

However, even as they reached their decision, events were already overtaking them. While Annelise, Mogens and David were discussing what to do, and as Nils Svenningsen tried in vain to contact Werner Best, the raids began. By 8pm, Wartheland, Lappland and Moero had docked at Langelinie.[32] Around the same time, Danish police patrols reported columns of trucks carrying German police in central Copenhagen, in Østerbro and on Amager.[33]

Starting at around 9:30pm, the Germans blocked all roads out of the city. Shortly afterwards, the phones were disconnected. Fifteen minutes later, a raid began in Købmagergade. German police officers formed a chain across the street, while smaller groups entered buildings and made arrests. At the same time, the German authorities informed the Danish Public Prosecutor’s Office for Special Affairs that “anti-government elements” would be arrested during the night. Around 10pm, the Copenhagen police issued orders that its officers should not help the Germans and should avoid areas where arrests were being made.

Over the next three hours, some 1,500 German police officers, a few hundred of whom had previously taken part in executions and deportations in Poland, carried out raids in Copenhagen. They usually operated in teams of three men, with assistance from locals – typically members of the Schalburg Corps (a Danish SS organisation) or Danish Waffen-SS volunteers who were home on leave and invited to take part.*[34]

Jewish families traditionally gather on Friday night, the eve of the Sabbath, and this particular week, Friday 1 October, was the second day of the Jewish New Year celebration, Rosh Hashana. The Germans may have anticipated that most of the approximately 5,000 people on their lists would be spending the evening at home or with family and friends. At the end of the night, however, only 232 people had been brought to the collection points established around the capital by Wachbataillon Kopenhagen. [35]* All of the others had gone underground.

The German police had been ordered not to break down doors if they did not open when they knocked. This was probably partly due to Best’s desire to minimise drama, and because broken front doors would “make an unpleasant impression and provide opportunities for theft, etc.,” which would be blamed on the occupying power. In some cases, however, the Germans did break open locked doors – and in at least 220 cases they gained access using keys handed to them by caretakers.[36]

At about 11:30pm, Nils Svenningsen finally managed to secure an audience with Werner Best in Dagmarhus. He tried in vain to persuade the Reich Commissioner to let the Danish Jews remain in the country by offering to have them interned by the Danish authorities. Best promised Svenningsen he would pass the proposal on to Berlin, but also made it clear that nothing would come of it. He explained that the raids exclusively concerned “full Jews”, i.e. not those of mixed heritage or married to non-Jews, and that Jewish property would probably not be seized. However, it is uncertain whether David’s marriage to Karen would have offered any sort of protection. They had been divorced for 15 years, and there were examples of Jewish people being deported even though they were married to non-Jews.*[37]

Around the time that Svenningsen met with Best, the German police arrived at Bredgade 51. There was no response when they rang the Drucker’s third-floor bell, but Eva’s door was opened, either by the nurse XX or the maid YY. Although YY did not really work there anymore, she was still in the flat, perhaps to help the nurse settle in before her first night looking after Eva.[38]

After being “tossed into the back of a truck”,[39] Eva was taken, along with XX, to the synagogue in Krystalgade where prisoners were being held temporarily. Ignoring the fact that it was a place of worship, the Germans smoked, drank, ate and profaned the altar.[40]

In the synagogue, Eva was recognised by others, including Elias Levin:

[...] in particular, I felt sorry for Mrs Eva Salomonsen from Bredgade who arrived on a mattress, covered in jewellery and terminally ill, along with two sisters from the Red Cross. The nurses pleaded for her with tears in their eyes but had to leave again without her.*[41]

The information that Eva was brought in on a mattress is consistent with the fact that she had been unable to walk for a long time, and with the testimony of another witness, businessman and actor Willy Salomon, that Eva was unconscious when she was removed from her home.[42] We do not know what jewellery Eva was “covered in” when she was taken, but on arrival at the synagogue, XX, according to a police report was:

asked whether Mrs. Salomonsen had any money, jewellery, etc., with her as she would need some means of payment where she was being taken.

[XX] explained that Mrs. Salomonsen had some money – just under 500 kroner – as well as her jewellery at home. She was advised by the German authorities in the synagogue that Mrs. Salomonsen should have the money and jewels with her. [XX] gave the address of Mrs. Salomonsen’s lawyer [Christian Langballe] so that the money might be sent, but that was not possible.[43]

Several others had also been encouraged to bring money and valuables, either when they were picked up at their homes or at the collection points. Some, like XX, were told that they would need them when they reached their unknown destination. Others were told that they would only be away from their homes for a few hours, but should take their valuables with them to avoid claims that anything had disappeared in their absence. During the raids, the Germans had taken the keys to the abandoned homes, which were later handed over to the Danish authorities, but did not confiscate money and valuables at that time.[44]

It took the German police some time to register and categorise the prisoners, but at 4am, the first ones were put on board trucks and, according to Levin, “filthy hay carts”, which departed in the direction of Langelinie. At the waterfront, Wartheland, Lappland and Moero awaited, along with 50 men from Wachbataillon Kopenhagen, while Danish police officers from Station 3 in Store Kongensgade blocked access to the pier at Pramrenden canal and the upper promenade.[45] Around 5.30am, Eva and XX were taken from the synagogue. As they were driven through Bredgade, the truck stopped at:

[...] Mrs. Salomonsen’s residence, where [XX] and a German soldier went to the flat. Mrs. Salomonsen’s jewellery and money – in a handbag – were handed over to him. [XX] explains that she then went with him to the truck, where she saw the German give the bag to Mrs. Salomonsen, placing it on her chest under her coat.

Since then, [XX] has not seen or heard anything about Mrs. Salomonsen and does not feel able to provide any further information about the case.[46]

M/S Wartheland

After the short stop, the truck continued to Langelinie, where the prisoners were taken on board Wartheland. The two other ships were not needed.

At the synagogue, some of those arrested had been released because they had convinced the Germans that they were not Jewish at all, or at least not “full Jews”, or that there were other reasons they should not be arrested. This sorting process continued on board Wartheland. The Danish Gestapo officer Paul Hennig “screamed [...] was anybody married to a non-Jew. Those who said yes were freed, others who he knew he bawled at for being Jew pigs and said that it was good that they had been rounded up.”[47]

This final sorting reduced the number of deported Jews to 198. They were joined by 143 imprisoned Communists.[48] Three more transports from Aalborg (2 October 1943) and Horserød (13 October and 23 November 1943) brought the number of deported Danish Jews to 472.

Ancestry and family relationships were not the only criteria that determined whether somebody would be deported or not:

[Willy Salomon] vehemently objected to being deported, as I am only what the Germans call a “half-Jew”, but they knew that I paid taxes to the Jewish congregation, and under the designation “Geltungsjude” [those considered Jewish under German law] they took me, too. They put us down in the hold, ancient men and women, infants and people in their prime, but still everyone remained pretty calm. I think we were petrified. It hadn’t really sunk in.[49]

Leo Säbel, 19 at the time, later wrote:

To begin with, we were gathered on the quayside, where a few who were married to non-Jews were released. The Germans were shouting and screaming and pushing us around. Everything had to be quick. “Schnell, schnell!” was the constant cry.

It was dark and cold.

A single floodlight lit up the gangway leading to the very big ship. We had to go up it, which was no problem for us youngsters, but some had been taken from the old people’s home in Krystalgade, and a lot of them couldn’t walk. It took a while to get them up there, but up they had to go. There was a sick old woman, I don’t know who she was. She couldn’t walk and they ended up putting her on a mattress or something like that. Then ropes were tied around it, and she lay there and was hoisted up with the help of a crane...[50]

The sight of the old lady on the mattress also made a big impression on two five-year-old girls, Birgit and Dina. Birgit asked her mother who she was and why she was lying there. Her exhausted mother did not know what to say and told her to stop staring and asking questions. Birgit and Dina lost sight of Eva when she was taken on board. Although they never saw her again, the memory remained vivid for both of them almost 80 years later.[51]

One of those told to help take Eva to the hold was Elias Levin:

She lay on deck groaning because of the cold. With great difficulty, we managed to carry her inside. She was placed in the middle of the ship along with the other sick people. She lay there, writhing about and constantly throwing off her blanket. I lay closest to her and tried, with some ladies, to look after her. But a Gestapo man became so angry with her groaning that he flung her against the wall, and she lay there unconscious. He grabbed the chance to steal a diamond bracelet from her. When he left, he threatened us with his revolver and signalled to us to keep quiet.[52]

The last to come up the gangway was Chief Rabbi Friediger:

They must have been terribly busy, as they struck me hard on the back, letting me know I had no time to pick up one of my bundles that I had dropped on the gangway, nor one of my galoshes that had slipped off my foot. Weiter! Weiter! [Get a move on!] they kept shouting. As soon as I was on deck, the gangway behind me was hoisted up! One last look towards Langelinie, towards the pier, towards the vast dome of the Marble Church, towards the big petroleum tanks – and again a hoarse shouted command: “Get down, Jew pig!” [...][53]

Wartheland set sail from Langelinie as planned at 10am on Saturday 2 October. It joined a convoy of three transport ships accompanied by a Sperrbrecher on their way down the Sound from Oslo to Stettin via Swinemünde, where Wartheland docked on Sunday 3 October at 7.40am. The prisoners were guarded by two or three SS men and a platoon of uniformed German police officers. The following day, Moero sailed back to Aalborg to resume scheduled services to and from Oslo, while Lappland docked at a shipyard in Copenhagen to undergo planned repairs.*[54]

This voyage, during which we were not allowed up on deck, lasted 24 long, foreboding hours. We had no idea what they were going to do with us. The ship stopped for hours in open sea [possibly while Wartheland was anchored in Copenhagen waiting for the convoy]. Are we going back home? Or is a hatch going to be opened so we all drown?

On the morning of Sunday 3 March, the command was given: Up on deck! A glorious blue sky stretched out above us. After 24 hours in a dark room, we saw the light of day again, and the sun shone more beautifully than ever before – or so it seemed.

We had reached Swinemünde, where a train was waiting for us.[55]

We were immediately taken from the ship and led into dirty, foul-smelling cattle wagons. Around 27 people were crammed into mine. There was very little room to move. Our wagons had hatches that could be opened, the Communists were crowded into cattle wagons with bars. Mrs Eva Salomonsen was hoisted up from the hold using steel wire ropes, and the other sick people were helped into the wagons.[56]

In Swinemünde, the Danish prisoners were split up. The Communists were sent east to the Stutthof concentration camp at Danzig, while the Jews went south.

[For] 3 days the train continued on and on, and we were given only a bit of rye bread. Neither children nor adults had access to a toilet, and uncertainty – or rather certainty about our fate – gave rise to all sorts of human responses. I will never forget the old teacher, Miss Goldschmidt, who was scared out of her wits. Or 88-year-old Mrs. Eva Salomonsen, who was unconscious when they arrested her at home on Bredgade and never really came round again. They treated the poor woman like a sack of coal, dragging her all the way to Theresienstadt, where she – and Ms. Goldschmidt – soon passed away.*[57]

During their three days on the train, the prisoners had no idea where they were going. Only when they reached Prague did the German sentries on the platform tell them that they were on their way to Theresienstadt.

Yellow star of David worn in Theresienstadt. From January 1942, Theresienstadt was a transit camp for those on their way to the death camps or mass execution sites in occupied Eastern Europe. A total of 88,323 men, women and children were transported to Riga, Izbica, Lublin, Maly Trostine, Treblinka and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

For German and Austrian Jews, Theresienstadt acted as a ghetto for both the elderly – without any significant account being taken of their needs – and for Jews whose position in society made it inappropriate to let them disappear without further ado. The “prominent” ones had better housing conditions than other prisoners but were not exempt from the death camps. The Danish prisoners were the only group who were not to be transported. However, the Danes did not know that. Like all prisoners in Theresienstadt, they lived in constant fear of being sent to their deaths.*[58]

The map shows Aussiger Barracks on the far left. Neue Gasse 3, where Eva died, is in the upper-right corner of field E II a. The West Barracks are just off Westgasse, at the bottom of the map (box C).

The 198 Jewish prisoners from Copenhagen arrived in Theresienstadt at 9–10pm on Tuesday 5 October. The train stopped in the small town of Bohusovice, a few kilometres south of Theresienstadt. From there, the prisoners were taken by truck to the Aussiger barracks at the north-west end of the fortified gateway between the ghetto and the outside world. They were given a meagre evening meal and slept on the stone floor, with only buckets for toilets. The following day, the Jewish community leader Paul Eppstein gave a speech to the new arrivals in the presence of the camp’s commander, SS-Obersturmführer Anton Burger. The prisoners were then once again loaded onto trucks and taken to the West Barracks (five structures originally built by and for the Sokol gymnastics movement before the German invasion of Czechoslovakia) at Westgasse, just outside the fortified walls. Already held here were 83 Danish prisoners who had been arrested in Jutland and on Funen at the same time as the raids in Copenhagen. They were transported by train – some all the way from Aalborg – and had arrived on the morning of 5 October.[59]*

The two truckloads of prisoners spent six days quarantined in the West Barracks. They were given yellow stars to sew on their clothes and assigned prisoner numbers. Eva’s number was XXV/2-168.[60] All of the money and valuables they had brought with them from home – and which had not already been stolen by the guards along the way or used as payment for services or information[61] – were confiscated.

Late on the evening of 12 October, the prisoners were split into groups and taken into Theresienstadt itself, which was completely blacked out.

Eva was taken straight to Neue Gasse 3, which served as accommodation for sick prisoners. It was not a hospital, more a kind of sick bay, or perhaps just a place to bring the most gravely ill prisoners, either for practical reasons or to ensure they received minimal care. The records show that Eva was already dying when she arrived and passed away on 14 October 1943. [62]

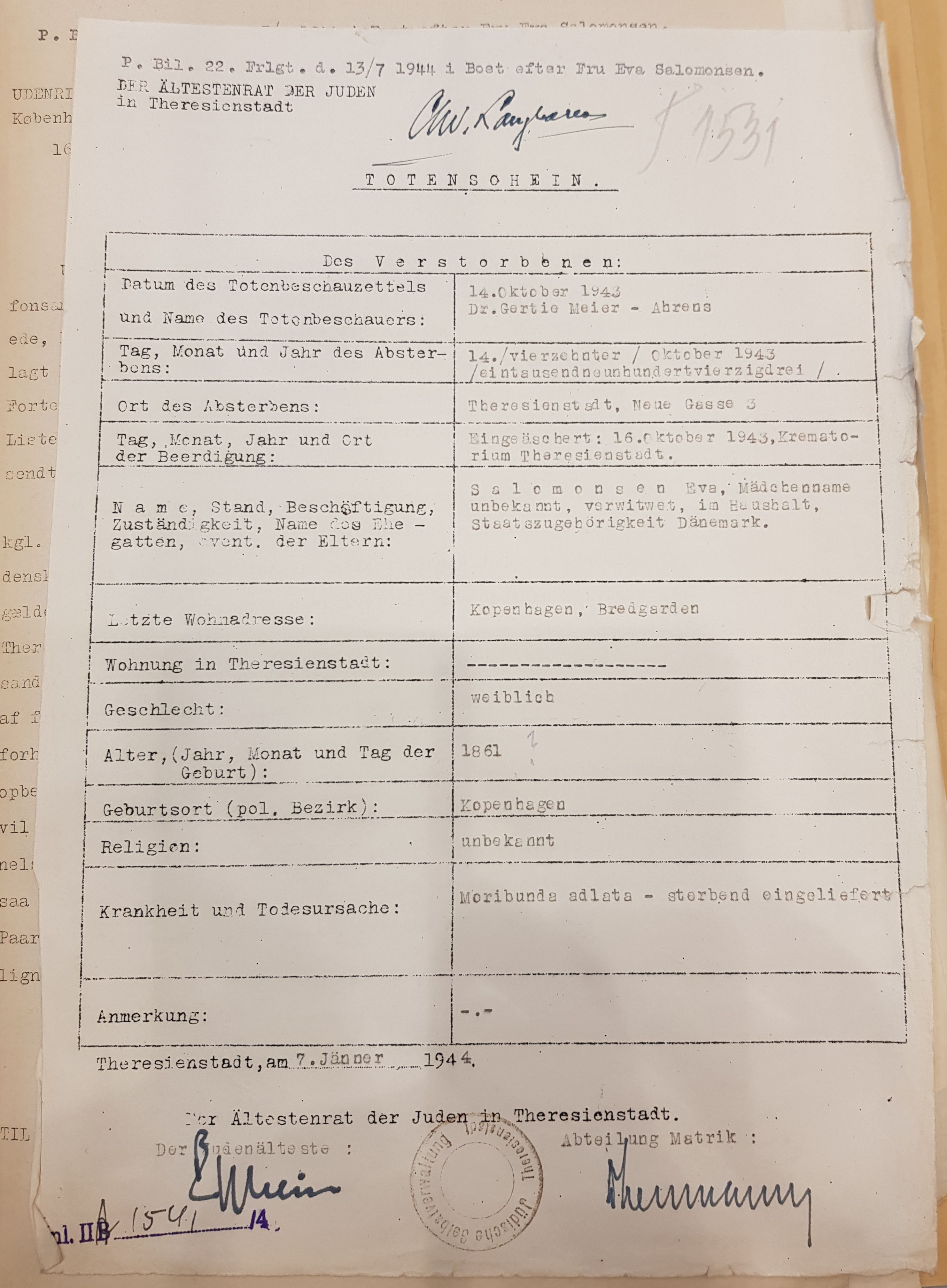

Eva’s death certificate issued by the Council of Jewish Elders. The inquest was conducted by Dr Gertrud “Gertie” Meier-Ahrens. Born in 1894 to a Jewish merchant family in the north-east German town of Dömitz, she graduated in 1922 and qualified in 1924. In 1938, as a Jew, she was stripped of the right to work in the profession and instead ran a “medical boarding house”. In 1939, like all Jewish women in Germany, she was forced to add the first name Sara. Her non-Jewish husband died in 1940. On 19 July 1942, she was deported from her Hamburg home. As a widow of a “privileged mixed marriage”, she was initially sent to the “preferential camp” (Vorzugslager) Theresienstadt. On October 9, 1944, she was sent to Auschwitz, where she was murdered.[63]

Ill.: List of deaths in Theresienstadt on 14 Octpber 1943

List of deaths in Theresienstadt on 14 October 1943 kept by the Ghetto’s Records and Funeral Service.[64]

There is no evidence of what happened to Eva’s body immediately after her death. At that time, the usual practice was that the dead were taken to the mortuary at Südstrasse 3, where they were washed in accordance with Jewish tradition (however, wrapping bodies in the traditional shroud (tachrichim) was not allowed). A rabbi would then oversee a short ceremony in a room set aside for the purpose.[65]* If the deceased was Danish, it was usually Max Friediger who spoke over the dead. He was only allowed to speak German, but would often add a final greeting in Danish before the deceased was taken to the

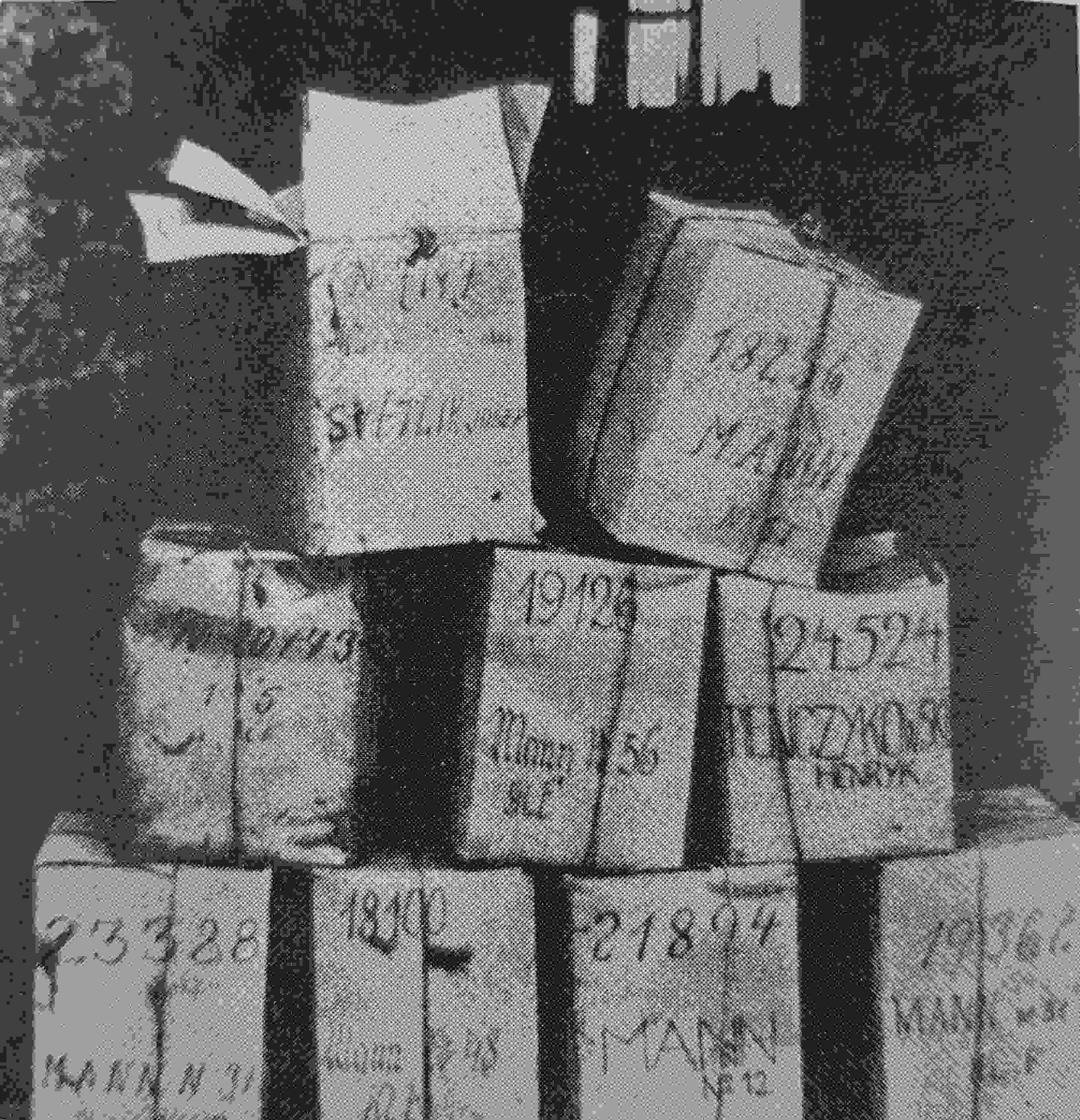

Eva was cremated on 16 October. Her ashes were put into a cardboard urn bearing her name and prisoner number, which was deposited in the columbarium in Südstrasse 4/6.*[66]

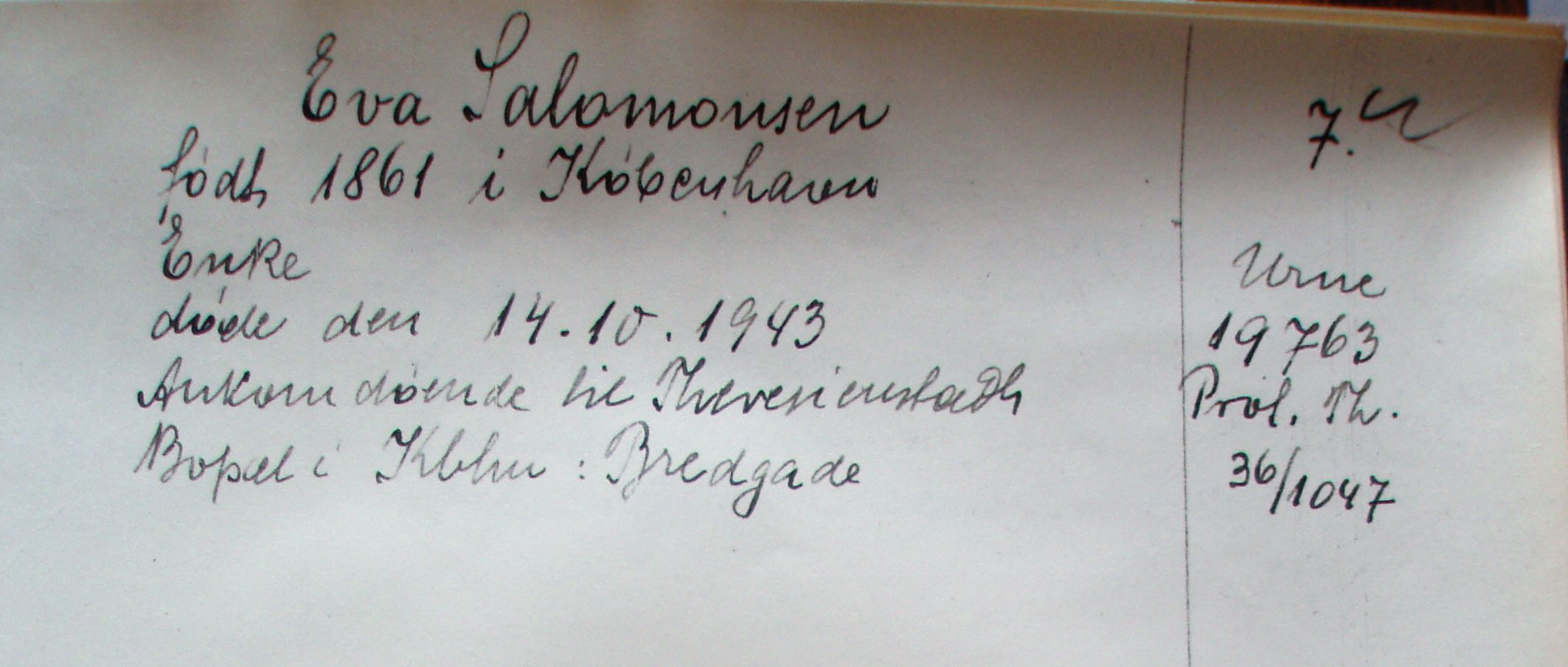

In Theresienstadt, the Danish chief rabbi Friediger kept a record the Danish prisoners who died in the ghetto . The erroneous information about her year and place of birth is probably due to the fact that prior to her death she was too sick to provide any information herself.

At first, before we made it to Theresienstadt, the bodies were buried [...]. But then so many died that they literally had to bury the dead 24 hours a day, so a crematorium with four furnaces was built. The corpses were burned without coffins, as wood was a precious commodity. After cremation, the ashes were collected in a cardboard urn and stored in a gallery. Each box had a name and number. I managed to gather the Danish urns and keep them together in one place. It was my intention – I promised the bereaved – to take the urns with me when we returned home. I visited them many times – the families of the deceased were not allowed in this casement – bringing them greetings from family and friends. After every visit, a strange calm would come over me. The dead, whom I knew – in several cases I had held their hand as they died – came alive before my eyes.[67]

Friediger was unable to keep his promise to the bereaved. On 1 November 1944, the male workers in the ghetto’s clothing repair shop were ordered to remove the urns from the columbarium. The next day, women and children (many of them Danes) were also put to work. They formed a human chain between the columbarium and a waiting truck and passed the urns from hand to hand. The workers were told that the urns would be placed in a Jewish burial ground. However, the contents of between 3,000 and 10,000 were buried near the Litoměřice concentration camp, and another 22,000 were emptied into the Eger river. Once the ashes had been disposed of, the 20 young men who had poured them into the river were shot. Those who had buried the ashes in Litoměřice probably suffered the same fate.

Cardboard urns.[69]

[1] Gelsted 1945/2013 p. 210.

[2] Jacobsen 1984 p. 77.

[3] Larsen 1967 p. 74

[4] Jacobsen 1984 pp. 197–98

[5] David had another daughter, Jette, from his previous marriage to Georgine Levin. They married in 1840 and Jette was born in 1841. Georgine died in 1843. A few years later, Jette slips out of this book’s field of view.

[6] Møller 1925 p. 17.

[7]* Jacobsen 1984b: “Tax lists from 1822 have been preserved and the system was as follows: local people were allocated a certain number of stones, fixed by the town council, according to their line of business, wealth and home. Their taxes were based on the number of stones. The lowest tariff was 1/8 stone, the second-lowest 1/4 stone, etc. Individuals assigned 1/4 stone paid twice as much as those with 1/8 stone. The highest tariff found in the material was H. Levinsohn at 17 stones in 1857.” Hirsch Levinsohn and his younger brother, the butcher Meyer Levinsohn, were among the few Jewish people in Bogense.

[8] Møller 1925, p.8.

[9] The Anti-Jewish Literary Feud” was a fierce debate that raged in newspapers, books and plays from 1813 onwards. It was sparked by the poet Thomas Thaarup’s translation from German of the anti-Jewish book Moses and Jesus, which concerned whether Jewish people could be integrated into Denmark. In his foreword, Thaarup accused them of being lazy, selfish, unreliable, unwilling to regard Denmark as their homeland, and intent on interfering in the business of the rest of the population. More broadly, the debate was about whether Denmark should be reserved for Christians and what it meant to be Danish. Thaarup’s anti-Semitic views were supported by the Court Chaplain, Christian Bastholm, while the poets Jens Baggesen and St. St. Blicher, among others, opposed their xenophobia (https://danmarkshistorien.dk/vis/materiale/uddrag-af-thomas-thaarups-forord-til-moses-og-jesus-1813/).

[10] Falk 2014.

[11] H.C. Andersen, Levnedsbog 1805-1831, p. 49, ed. Hans Brix, 1926.

[12] Jensen 1985, p. 14. The cry “Hep, hep, hep!” had come to Denmark from Germany, where it had accompanied violent anti-Jewish unrest across the country, from southern Germany to Hamburg. The original meaning, if there ever was one, is uncertain, but its use in Denmark is indicative of the German inspiration for the rioting (Blüdnikow 2019a, pp. 32-33; Blüdnikow 2019b).

[13] https://www.sa.dk/ao-soegesider/da/billedviser?epid=21417468#349161,69366403

[14] Odense Mosaiske Menighed, Ministerialbog; folketællinger, Odense, 1840 og 1845

[15] Møller 1925, p. 17.

[16] Hansen & Jacobsen (ed) 1988 p. 15

[17] Kontraministerialbogen for Bogense Mosaiske Menighed (Records of the Bogense Mosaic Congregation).

[18] Nimb 1888 pp. 58

[19] Møller 1925, p. 14.

[20] Møller 1925, p. 17.

[21] Werner Best an das Auswärtige Amt 8. September 1943, WBK; Bak 2004 b; Kreth & Mogensen 1995, p. 17. Kirchhoff 1993; Fracapane, 2021, pp. 62–66. Best’s motives are hotly debated.

[22] Werner Best an das Auswärtige Amt 8. September 1943, WBK.

[23] Fracapane, 2021, Ch. 2; Bak 2004, pp. 461-472; Levin, handwritten memoir, p. 1 (FHM). Best met with both Hennig and Christensen on 17 September (Best’s calendar; Werner Best an das Auswärtige Amt 8. September 1943, WBK); about the two raids and the seized material. Jerichow 2003, pp. 107-108; 119.

[24] Fracapane 2021, p. 49; Max Rothenborg: Break-in at the Mosaic Community – 1 September 1943; Nils Svenningsen; Notice of the break-in at the Mosaic Community – September 17, 1943 (Jerichow 2013). After arriving from Oslo, III. Bataillon/Polizeiregiment 15 marched through Copenhagen in broad daylight. Several of the men reportedly spoke openly and indiscreetly about why they were in Denmark (Curilla 2020, p. 134; 150–151).

[25] About the three ships: RM 7-2162; RM 45-III-245; on rail transport from Aalborg: Fracapane 2021, p. 50.

[26] Lundtofte 2003; Curilla 2020, p. 135.

[27] From 2021, pp. 48-50; Kirchhoff 2013, pp. 154-178.

[28] Lausten 2020, pp. 169-182; Jerichow 2003, p. 164; 174-175, 180.

[29] Paul Eduard Drucker sailed to the Swedish port of Limhamn from Nexø on the Danish island of Bornholm on 7 October. His wife Elsebet (who was not Jewish) and the couple’s four children sailed to the Swedish island of Ven from Tuborg Havn in Copenhagen on 19 October, on a boat carrying 28 refugees. Mrs Drucker paid DKK 3,000 for the crossing (https://safe-haven.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/Uppgift_Drucker__Paul_Eduard.pdf; https://safe-haven.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/Uppgift_Drucker__Elsebet__foedt_Bording_.pdf). Domestic worker and home nurse: Police report of 23 May 1944 (RA: Prag, diplomatisk repræsentation: Gruppeordnede sager (aflev. 1979) (1939–1973) 130: 120 N 1.II – 144 D 29 (a).I; Annelise’s diary; “almost dying”: Jane Andreasen (née. Gram).

[30] Annelise’s diary does not indicate the source of Paul Johansen’s information. There are various ways in which the now widespread and fast-moving rumours may have reached his ears. One might have been Professor Harald Bohr, who was a member of the Nye Danske af 1864 Control Committee, and who had already fled to Sweden on the night of 29–30 September with his son, Ole, his brother (the nuclear physicist) Niels Bohr and Niels’ wife, Margrethe, as well as 10 other family members. They escaped on a fishing boat from Copenhagen’s South Harbour (https://safe-haven.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/Polis_rapport_Bohr__Harald_August.pdf).

[31] Annelise’s diary.

[32] Wartheland had been in Copenhagen since 8 September for repairs to the magnetic unit that protected the ship from mines (RM 45 III/243; Werner Best to the Foreign Ministry, 29 September 1943, Telegram no. 1162, WBK). Moero, which normally plied the route between Oslo and Aalborg, had been commanded on 29 September to replace Monte Rosa and its captain. The latter had been under the command of Captain Bertram, who along with the German maritime transport manager in Aarhus, Friedrich Wilhelm Lübke, held anti-Nazi views. Bertram told Naval Command that Monte Rosa, which was in dock in Aarhus, was having engine problems. Lübke had made sure that the message about the impending raids was leaked to Danes in Aarhus, who may have passed it on and helped warn Danish Jews (Matlok 2013; Præstgaard 2013; “A German naval officer gave the warning to the Danish Jews”, article in Jyllands-Posten, 25 January 1946; RM 7-2162).

[33] The overall depiction of the action against the Danish Jews is based mainly on Kreth & Mogensen 1995, Chapter 2. Some of the records that confirm the work of the two historians have since been made available (Jerichow 2013).

[34] Three battalions of the German Police (about 1,300–1,400 men) took part: Polizei-Wachbataillon ”Dänemark”, Reserve-Polizeibataillon 65 ”Cholm” (I. Bataillon ”Cholm”/Polizeiregiment 25) and III Bataillon/Polizeiregiment 15. They were aided by about 250 members of the Gestapo and the intelligence and security agency SD. According to Gustav von Dardel, the Swedish Ambassador in Copenhagen, there were 1,800 German police officers in Copenhagen on 5 October 1943 (Curilla 2020, 130-143; 150-154; Kreth & Mogensen 1995).

[35] Wachbataillon Kopenhagen and the police regiments belonged to the army’s Ordnungstruppen, i.e. units that helped maintain order and discipline behind the frontlines and carried out guard duty, ceremonial events, etc. (Andersen 2020, 153, 176; http://www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de/Gliederungen/WachEinheiten/WBKopenhagen.htm).

[36] Kreth & Mogensen 1995, pp. 31-35; the quote: Werner Best to the Foreign Ministry, 5 October 1943, WBK p. 277.

[37] Bak 2002, p. 57. Svenningsen’s desperate offer apparently did not involve the Danish police making arrests, only that the Danish authorities would intern those arrested by the Germans or who turned themselves in. Not only were Svenningsen and his colleagues unaware of the true purpose of the arrests and deportations, they also failed to understand just how little store Best and his accomplices would have set by any such agreement. Above all, they did not know that a mass exodus of Jewish people was already in full swing and would pick up speed in the next few days. Any illusion of safety in camps on Danish soil and under Danish management and guards would have endangered those who might otherwise have sought safety in Sweden, as the Germans would have been able to pick them up at any time. The genesis of the proposal and the permanent secretaries’ discussions of it are seen in the material reproduced in Jerichow 2003; Werner Best to the Foreign Office 2 October 1943 (WBK, pp. 247-248). Best had not secured approval in advance from RSHA for his promise to Svenningsen. On 2 November, SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann arrived as the RSHA representative to Copenhagen to discuss the issue with Best. The result was that Jews over the age of 60 would no longer be arrested and deported (however, those already arrested would not be released, and the vast majority of the other Danish Jews had long since fled to Sweden or at least gone underground); “half-Jews” and those in mixed marriages would have their case investigated and might be released. The Danish authorities drew attention to 20–30 such cases of the “wrongly deported”, but only five were sent home from Theresienstadt. In addition, a 102-year-old Jewish woman who was presumed to have gone underground in Denmark was allowed to stay in the country (Fracapane 2021, pp. 60-61); Werner Best to the Foreign Office, 28 October 1943 and Werner Best to the Foreign Office 3 November 1943 (WBK, p. 388, 444).

[38] Christoffersen: “Lidt om Eva Salomonsen, født Wagner” (A little about Eva Salomonsen, née Wagner); Det. Const. E Rose: “Muligt mistænkeligt Forhold m.H.t. Smykker” (Possibly Suspicious Circumstances concerning Jewellery), 7 October 1943–23 May 1944; The Danish Embassy in Berlin to the Foreign Ministry, “Death: Mrs Eva Salomonsen, née Wagner, 22 February 1945; Letter from Foreign Ministry to the Royal Embassy in Prague, 13 February 1946 (RA, 2-0435 Prag diplomatisk repræsentation).

[39] A few days later, the caretaker described the arrest to Annelise’s in-laws (Annelise’s diary, Sunday, October 3, 1943).

[40] Salomon 1945.

[41] Levin, handwritten memoir, p. 4 (FHM). The mention of the two Red Cross sisters, which appears in both the handwritten and printed editions (Levin 2001), is probably based on a misunderstanding or poor memory. One of them may have been the live-in nurse XX – and according to Levin, other prisoners also arrived along with nurses.

[42] Salomon 1945.

[43] Det. Const. E Rose: “Muligt mistænkeligt Forhold m.H.t. Smykker” [Possibly suspicious circumstances in connection with jewellery], 7 October 1943–23 May 1944 (RA, 2-0435 Prag, diplomatisk repræsentation).